AP Syllabus focus:

‘Explain how water’s polar covalent bonds create molecular polarity and enable hydrogen bonding between water molecules and other biological molecules.’

Water’s unusual biological usefulness comes from how electrons are shared within each H2O molecule. Unequal sharing produces partial charges, making water polar and allowing extensive hydrogen bonding that organizes water and influences interactions with biomolecules.

Water’s Structure and Electron Distribution

Water (H2O) has one oxygen atom covalently bonded to two hydrogen atoms. Oxygen attracts shared electrons more strongly than hydrogen, so the O–H bonds are polar covalent bonds (covalent, but with unequal electron sharing).

Electronegativity: a measure of an atom’s ability to attract shared electrons in a covalent bond.

Because oxygen is highly electronegative, electron density is pulled toward oxygen, creating partial negative charge (δ−) on oxygen and partial positive charge (δ+) on each hydrogen.

Shape Reinforces Polarity

Water is not linear; it is bent due to electron pair repulsion around oxygen. This geometry means the bond dipoles do not cancel, so the molecule has a net dipole with a negative “end” near oxygen and positive “ends” near hydrogens.

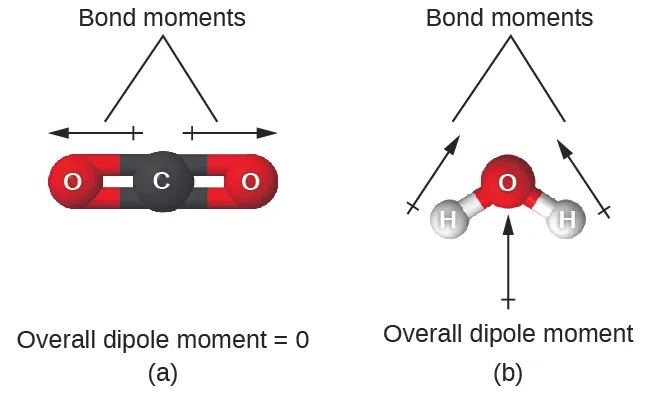

This figure compares a linear molecule (CO₂) whose bond dipoles cancel with bent water (H₂O), where the O–H bond dipoles sum to a net dipole moment. It visually links molecular geometry to overall polarity, explaining why water has distinct partial-positive and partial-negative regions. Source

Molecular Polarity

Polarity describes an uneven distribution of electrical charge across a molecule. In water, polarity is an emergent result of:

O–H electronegativity difference (unequal sharing of electrons)

Bent molecular shape (dipoles add rather than cancel)

Polar molecules interact strongly with other charged or polar substances because opposite partial charges attract. This is the basis for many aqueous interactions in cells, including the positioning of water around ions and polar functional groups.

Molecular polarity: an unequal distribution of charge within a molecule that creates partial positive and partial negative regions (a dipole).

Hydrogen Bonding Between Water Molecules

Water’s polarity enables hydrogen bonding: attractions between the δ+ hydrogen of one water molecule and the δ− oxygen of another.

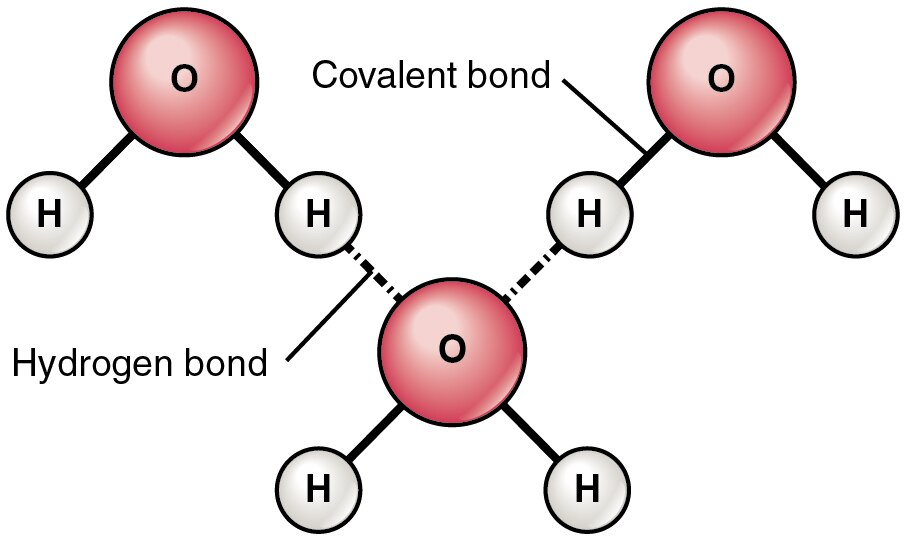

This schematic shows multiple water molecules with δ+ and δ− labels and dotted lines representing hydrogen bonds between neighboring molecules. It emphasizes the directional nature of hydrogen bonding—hydrogen atoms align toward electron-rich oxygen atoms—helping explain how many weak bonds can collectively create an organized network. Source

Hydrogen bonds are weaker than covalent bonds, but they form in huge numbers and can collectively produce strong, organized effects.

Hydrogen bond: a weak attraction between a partially positive hydrogen (covalently bonded to an electronegative atom) and a partially negative electronegative atom (commonly oxygen or nitrogen).

Key Features of Water–Water Hydrogen Bonds

Directional attraction: the δ+ H of one molecule aligns toward the δ− O of another.

Transient network: hydrogen bonds continually break and re-form in liquid water, creating a dynamic structure.

Many-to-many interactions: a single water molecule can participate in multiple hydrogen bonds over time because it has two hydrogens (potential donors) and oxygen electron density (acceptor).

Hydrogen Bonding with Biological Molecules

Water can form hydrogen bonds not only with other water molecules but also with other biological molecules that contain electronegative atoms and polar covalent bonds. This occurs when water’s δ+ hydrogens are attracted to partially negative atoms in biomolecules, or when water’s δ− oxygen is attracted to partially positive hydrogens on biomolecules.

Common Hydrogen-Bonding Partners in Biology

Water most often hydrogen-bonds with oxygen (O) and nitrogen (N) atoms found in polar functional groups, including:

Hydroxyl (–OH): water can both donate and accept hydrogen bonds with alcohol groups on sugars and other molecules.

Carbonyl (C=O): the oxygen is partially negative and can accept hydrogen bonds from water’s δ+ hydrogens.

Amino (–NH2 / –NH–): hydrogens attached to nitrogen can donate hydrogen bonds to water’s oxygen; nitrogen’s lone pair can accept in some contexts.

Phosphate-associated oxygens: often carry partial or full negative character and strongly attract water’s δ+ hydrogens.

What Hydrogen Bonding Enables (Mechanistically)

Hydrogen bonding helps explain how molecules behave in aqueous environments by promoting:

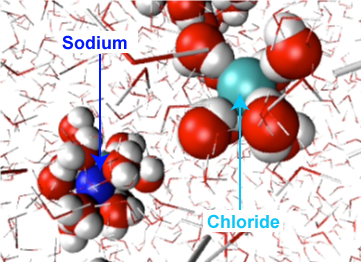

This diagram shows hydration shells forming around Na⁺ and Cl⁻, with water molecules oriented so that oxygen (δ−) faces the cation and hydrogens (δ+) face the anion. It illustrates how water’s polarity drives ordered interactions in solution, providing a mechanistic basis for ion solubility and structured aqueous environments. Source

Hydration shells: ordered layers of water around polar groups and ions due to repeated hydrogen-bond and electrostatic attractions.

Stabilisation of polar conformations: polar regions of macromolecules can remain exposed to water because hydrogen bonding is energetically favourable.

Selective interaction patterns: molecules with many polar groups tend to interact extensively with water, whereas nonpolar surfaces cannot hydrogen-bond effectively with water.

Why Polarity and Hydrogen Bonds Matter for Cells

In biological contexts, water’s polarity and hydrogen bonding capacity mean that water is not just a background solvent; it actively participates in molecular organisation. In crowded cellular environments, hydrogen bonds:

create highly interactive aqueous surroundings that influence how polar regions of biomolecules are oriented

compete with (and sometimes replace) hydrogen bonds within or between biomolecules, affecting which interactions persist

allow rapid, reversible associations that support dynamic biological processes

FAQ

Not in a meaningful, direct way. Nonpolar molecules lack strongly partial charges and suitable electronegative atoms, so they cannot act as hydrogen-bond donors or acceptors.

Water may still arrange into an ordered layer around nonpolar surfaces, but that organisation reflects water–water hydrogen bonding rather than water bonding to the nonpolar molecule.

Hydrogen must be covalently bonded to a strongly electronegative atom (most commonly O or N in biology). This pulls electron density away from H, making it sufficiently partially positive to be attracted to another electronegative atom.

No. Ionic bonds involve full charges (cations and anions) and strong electrostatic attraction.

Hydrogen bonds involve partial charges and are generally weaker, though many hydrogen bonds together can be highly influential.

If water were linear, the two O–H bond dipoles would largely cancel. The bent geometry ensures the dipoles reinforce each other, producing an overall dipole that enables extensive hydrogen bonding.

A single water molecule has:

two hydrogens that can donate hydrogen bonds

an oxygen with electron density that can accept hydrogen bonds

Because bonds are transient, water can participate in several hydrogen-bond interactions over time, constantly rearranging its partners.

Practice Questions

Explain why water molecules are polar. (2 marks)

Oxygen is more electronegative than hydrogen, so O–H bonds are polar covalent / electrons are shared unequally (1)

Bent shape means dipoles do not cancel, giving a net partial negative region near oxygen and partial positive near hydrogens (1)

Describe how polar covalent bonds in water lead to hydrogen bonding, and explain how water can hydrogen-bond with other biological molecules. (6 marks)

O–H bonds are polar covalent due to electronegativity difference (1)

Water has partial charges (δ− on oxygen, δ+ on hydrogens) / is a dipole (1)

Hydrogen bond forms between δ+ hydrogen of one molecule and δ− oxygen of another (1)

Hydrogen bonds are weak individually but form frequently as a network (1)

Water hydrogen-bonds with electronegative atoms in biomolecules (oxygen or nitrogen) in polar functional groups (1)

Correct example of a functional group/atom that can hydrogen-bond with water (eg hydroxyl, carbonyl oxygen, amino group) (1)