AP Syllabus focus:

‘Explain how water’s high heat of vaporization enables evaporative cooling and contributes to maintaining body temperature in organisms.’

Water can stabilise body temperature not only by storing heat, but also by removing it. Evaporation is an especially effective cooling mechanism because it exploits water’s unusually high energy requirement to change state.

Heat of Vaporisation: Why Evaporation Costs So Much Energy

Water molecules are strongly attracted to each other, so separating them into a gas requires substantial energy input. This energy is drawn from the surroundings (for example, skin, leaf surfaces, or respiratory passages), reducing thermal energy there.

Heat of vaporization: The amount of energy required to convert 1 gram of a liquid into a gas at its boiling point (without changing temperature).

A high heat of vaporization means:

Many water molecules must absorb a large amount of energy before they can escape as vapour.

The energy absorbed is “hidden” as potential energy in the gas phase rather than remaining as kinetic energy that would keep the surface warm.

Evaporation can occur below the boiling point, so cooling can happen at typical biological temperatures.

Molecular Basis (What Makes Water Unusual)

Water’s high heat of vaporization arises because:

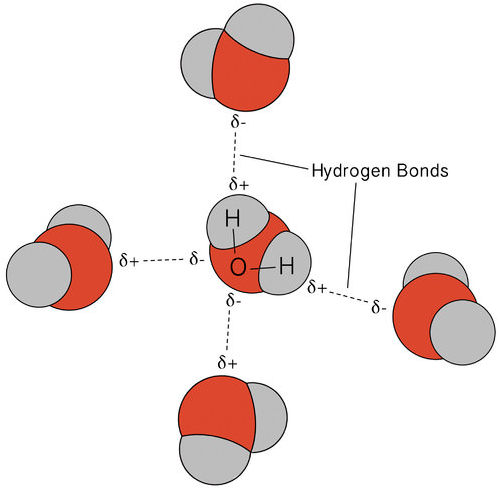

Diagram illustrating hydrogen bonding among neighboring water molecules, with dashed lines indicating hydrogen bonds and partial charges on O and H. The key takeaway is that a surface molecule is stabilized by multiple simultaneous attractions, so evaporation requires enough energy to disrupt several interactions at once. This molecular picture helps explain why water’s heat of vaporization is unusually high compared with less strongly hydrogen-bonded liquids. Source

Intermolecular attractions must be overcome for molecules to leave the liquid.

The strongest effect comes from the need to disrupt multiple attractions for each escaping molecule, so evaporation selectively removes energy from the liquid surface.

Evaporative Cooling: How Temperature Drops

Evaporative cooling is the direct biological payoff of water’s heat of vaporization.

Evaporative cooling: Cooling that occurs when the highest-energy molecules at a liquid surface evaporate, lowering the average kinetic energy (temperature) of the remaining liquid.

Because the most energetic molecules are most likely to evaporate:

The remaining liquid has a lower average molecular kinetic energy.

Lower average kinetic energy corresponds to a lower temperature at the surface being cooled.

Continued evaporation can remove heat rapidly, especially when air movement and low humidity favour evaporation.

Quantifying Heat Loss (Conceptual Use)

Biologists often represent evaporative heat loss using latent heat.

= heat energy absorbed from the organism or surface (J)

= mass of water evaporated (g)

= energy required to evaporate 1 g of water (J/g)

This relationship emphasizes that small amounts of evaporated water can remove large amounts of heat when is high.

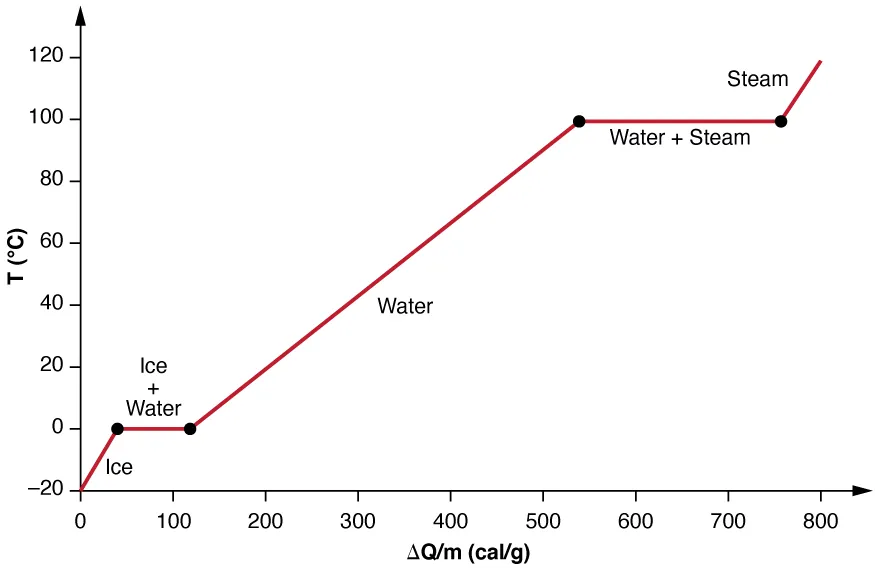

Heating curve for water (temperature vs. energy added) showing phase-change plateaus. The extended flat region at 100°C represents the large latent heat of vaporization: substantial energy is absorbed while temperature remains constant because energy is invested in overcoming intermolecular attractions rather than increasing kinetic energy. This provides a clear visual link to for evaporative heat loss. Source

How Organisms Use Evaporative Cooling to Maintain Body Temperature

Evaporative cooling helps maintain body temperature by preventing overheating when heat gain exceeds heat loss by other means (radiation, conduction, convection). Key biological contexts include:

Animals: Sweating and Respiratory Evaporation

Sweating: Water secreted onto the skin evaporates, absorbing heat from the skin and superficial tissues.

Panting: Rapid ventilation increases evaporation from moist respiratory surfaces, absorbing heat from tissues lining the airways.

Behavioral support often increases effectiveness (seeking shade, spreading saliva on fur, increasing airflow by fanning or moving).

Cooling effectiveness depends on the evaporation rate:

Evaporation increases when surrounding air is drier and moving.

Evaporation decreases when air is humid, limiting the gradient for water vapour to leave the surface.

Plants: Transpiration as Thermal Protection

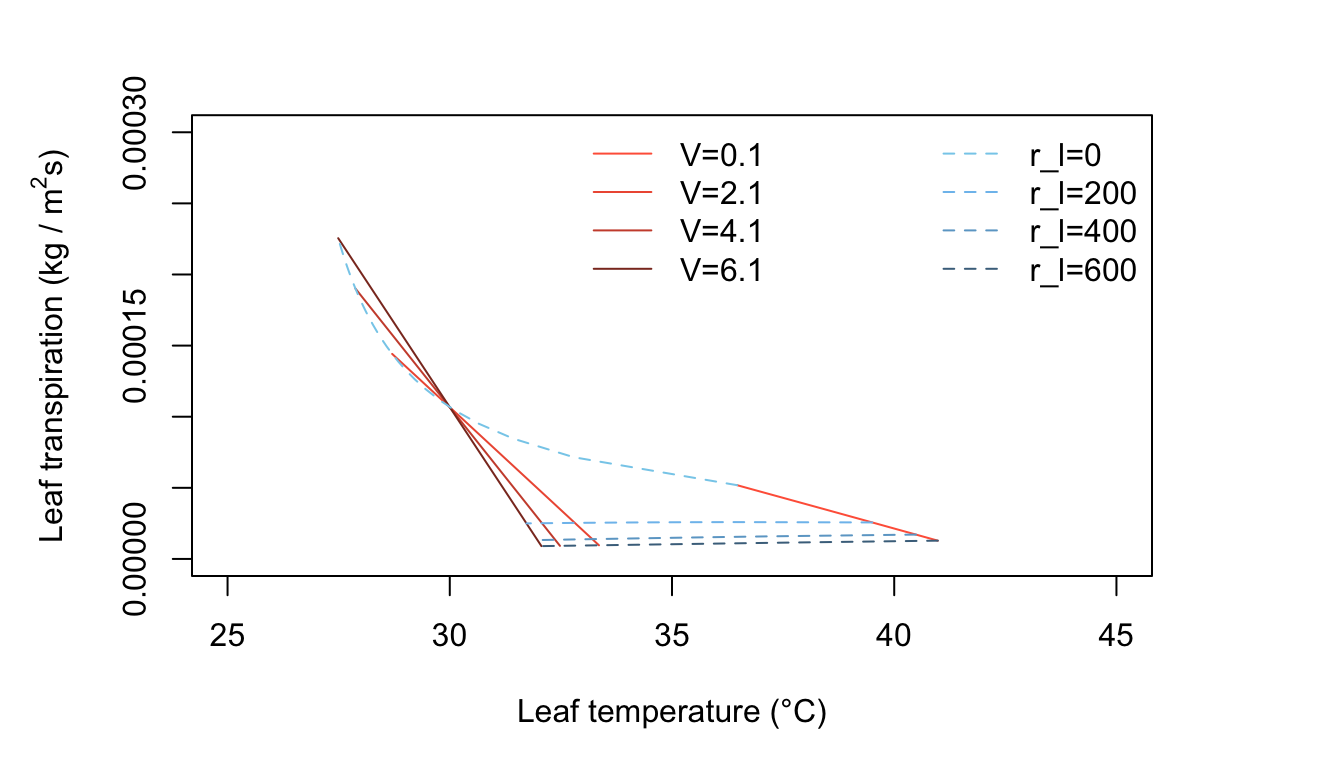

Transpiration (evaporation of water from leaf surfaces) can reduce leaf temperature during high solar input.

Lower leaf temperature protects temperature-sensitive enzymes and membranes, supporting ongoing metabolism during warm conditions.

When evaporation is restricted, leaves can overheat, increasing physiological stress.

Graph relating leaf transpiration rate to leaf temperature, illustrating how evaporative water loss can shift leaf temperature relative to air temperature. Conditions that increase evaporation (e.g., higher wind speed or lower resistance to vapor diffusion) tend to enhance cooling, while restricted transpiration is associated with warmer leaves. This figure helps connect transpiration to thermal regulation as an environment-dependent physiological process. Source

Trade-offs Relevant to Homeostasis

Using evaporation to control temperature can create competing demands:

Cooling requires water loss, so organisms must balance heat loss with hydration status.

Under hot, dry conditions, evaporation is powerful but can be water-expensive; under hot, humid conditions, evaporation is water-inefficient because less water evaporates per unit time, reducing cooling.

FAQ

High humidity reduces the water vapour gradient between skin/airways and the air.

Less sweat evaporates per unit time, so less heat is removed, even if sweat production increases.

Moving air carries away the thin, humid boundary layer next to the skin or leaf.

This maintains a steeper diffusion gradient for water vapour, increasing evaporation rate.

Small animals have high surface-area-to-volume ratios and can lose water quickly.

Rapid dehydration can limit continued evaporation and compromise temperature regulation.

No. Some rely more on panting, gular fluttering, or spreading saliva/secretions on body surfaces.

The dominant strategy depends on anatomy, habitat, and water availability.

Closing stomata restricts water loss, but it also limits evaporation from leaf surfaces.

Reduced transpiration lowers evaporative cooling, allowing leaf temperature to rise under strong sunlight.

Practice Questions

Explain why evaporation of sweat cools the skin. (2 marks)

Evaporation requires energy/heat to change water from liquid to gas (1)

That energy is taken from the skin, lowering temperature (1)

A mammal begins panting during a hot afternoon. Using the concept of water’s high heat of vaporisation, explain how panting helps maintain body temperature and state one environmental condition that would reduce its effectiveness. (5 marks)

Water has a high heat of vaporisation, so a lot of energy is needed for water to evaporate (1)

During panting, evaporation from moist respiratory surfaces increases (1)

The energy for evaporation is absorbed from body tissues/blood in the respiratory passages (1)

This removes heat from the body, helping to prevent overheating/maintain body temperature (1)

Effectiveness reduced in high humidity (or still air), because evaporation rate decreases (1)