AP Syllabus focus:

‘Describe how hydrogen bonds between water molecules produce cohesion, adhesion, and surface tension important for many biological processes.’

Water’s polarity allows extensive hydrogen bonding, giving liquid water unusual collective behaviors. In biology, these emergent properties—cohesion, adhesion, and surface tension—help move fluids, maintain continuous water columns, and shape interactions at surfaces.

Hydrogen Bonding as the Molecular Basis

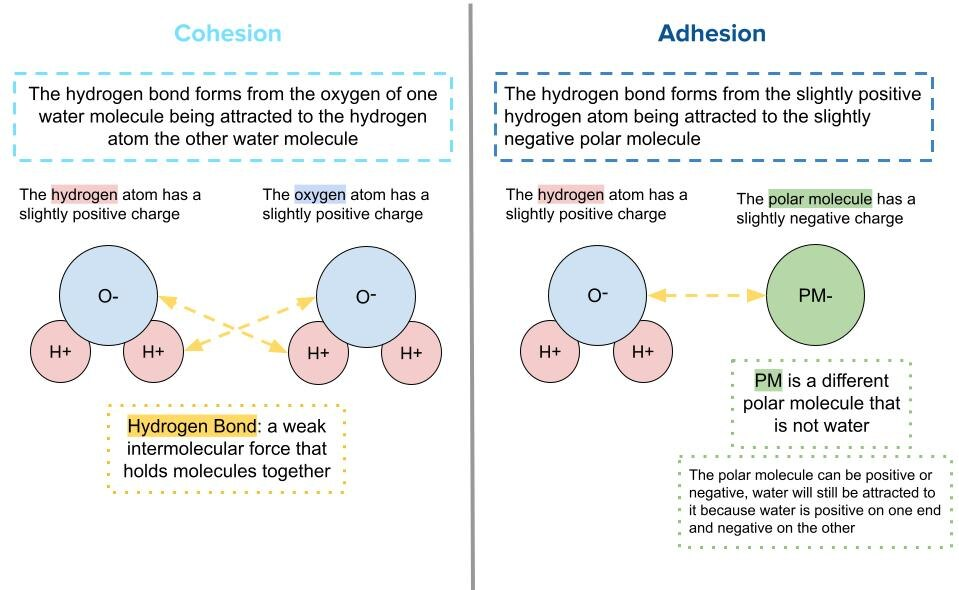

Water molecules form transient hydrogen bonds because oxygen is partially negative and hydrogens are partially positive. Individually, hydrogen bonds are weak, but in bulk water they create a dynamic network that resists separation and organizes water at interfaces.

Cohesion: Water Molecules Sticking to Each Other

Cohesion arises when hydrogen bonds hold water molecules together, making water behave like a connected mass rather than independent molecules.

This diagram contrasts cohesion (attraction among water molecules) with adhesion (attraction between water and another material). It visually reinforces that both behaviors arise from polar interactions (often hydrogen bonding), but they differ in what is attracting what. Source

Cohesion: The attraction between molecules of the same substance; in water, primarily due to hydrogen bonding among water molecules.

Cohesion matters biologically because it helps water transmit pulling forces through continuous columns of liquid. Key implications include:

Continuity of water in narrow tubes (for example, plant vascular tissues), where cohesive forces help prevent the column from breaking.

Droplet formation on biological surfaces, affecting how fluids spread, bead, or remain localized.

Resistance to mechanical disruption in thin films of water covering cells or tissues.

Adhesion: Water Sticking to Other Materials

When water encounters another surface, it can form hydrogen bonds (or other polar interactions) with that surface. This attraction can compete with and sometimes exceed water-water cohesion.

Adhesion: The attraction between molecules of different substances; for water, attraction to other polar or charged surfaces through hydrogen bonding and related interactions.

Adhesion is strongest on hydrophilic surfaces (polar or charged), such as many proteins, polysaccharides, and cell wall materials. Biological roles include:

Wetting of tissues: water spreads along polar biological surfaces, supporting thin liquid layers needed for diffusion and transport.

Capillary action: in very narrow spaces, adhesion to the walls plus cohesion within water allows liquid to rise or move against gravity.

Stabilising fluid contact with membranes and extracellular matrices, helping maintain hydration at cell and tissue boundaries.

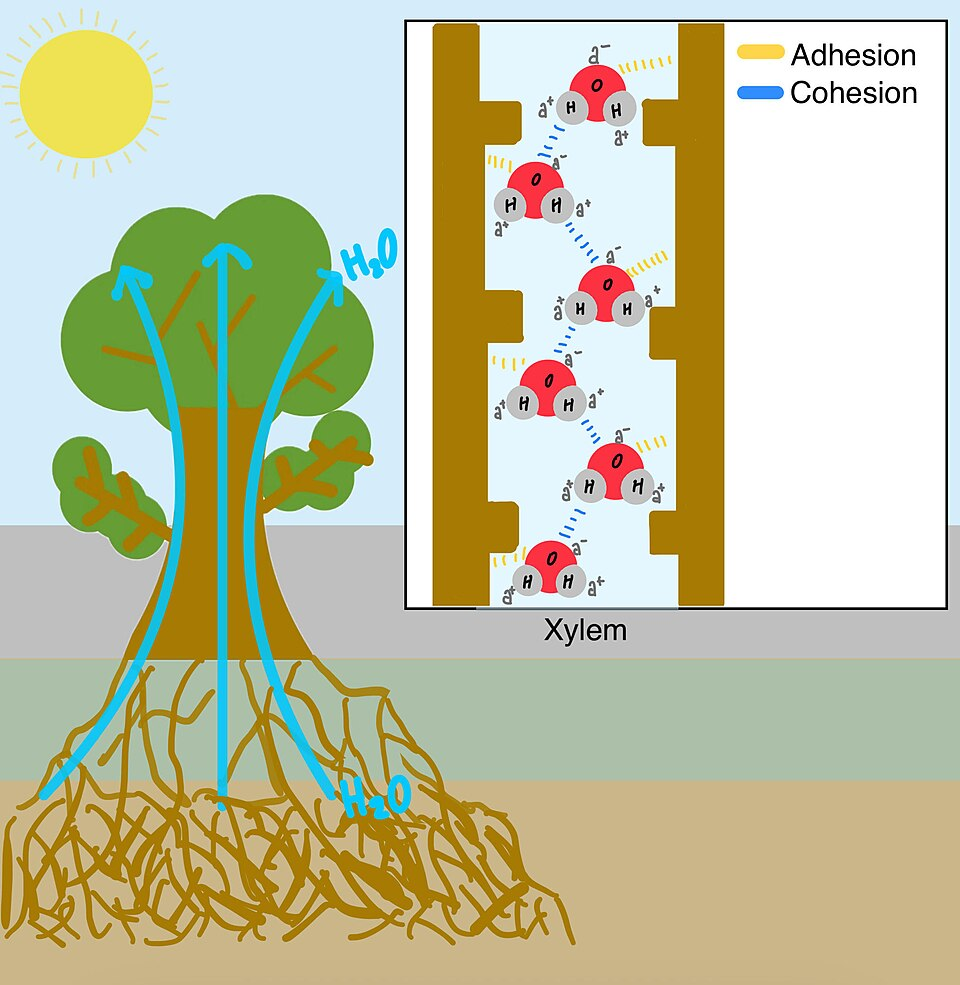

Cohesion + Adhesion Together: Capillary Effects in Living Systems

Cohesion and adhesion usually operate simultaneously. In confined spaces (small-diameter tubes, pores, or intercellular gaps), adhesion draws water to the surface while cohesion pulls additional water molecules along, allowing a moving column rather than isolated molecules.

This combined behavior supports:

This labeled figure shows how cohesion between water molecules and adhesion to xylem walls work together to pull water upward in plants. The inset links the macroscopic water column to the molecular interactions (hydrogen bonds for cohesion and attractions to the wall for adhesion). Source

Upward movement in small conduits where surface contact is high relative to volume.

Maintenance of continuous films of water in porous biological materials.

Efficient distribution of dissolved solutes, because solutes move with the bulk flow of cohesive water.

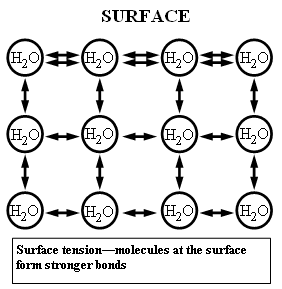

Surface Tension: A Property of Water’s Surface

Molecules at the surface of water have fewer neighboring water molecules above them, so hydrogen bonding creates a net inward pull.

This resource explains surface tension by comparing forces on water molecules in the bulk versus at the surface. Because surface molecules lack neighbors above, cohesive attractions produce a net inward pull, making the surface behave like a stretched film that resists deformation. Source

The surface behaves like a stretched elastic layer that resists being broken.

Surface tension: The resistance of a liquid’s surface to being stretched or penetrated, caused by cohesive forces among surface molecules.

Surface tension is biologically significant because it affects how organisms interact with air–water boundaries:

Support at interfaces: small organisms can be supported if their weight does not exceed the surface’s ability to resist deformation.

Formation of stable surface films that influence gas exchange and how liquids spread across tissues.

Control of droplet and bubble behaviour, affecting how fluids partition into compartments or remain as continuous layers.

How Biological Molecules Influence these Properties

Many biological surfaces are chemically patterned, containing both polar and nonpolar regions. This changes local adhesion and can modify surface tension:

More polar/charged groups generally increase water adhesion and wetting.

More nonpolar regions reduce adhesion, promoting beading and maintaining distinct water boundaries.

Surface-active molecules (with hydrophilic and hydrophobic parts) can disrupt hydrogen bonding at the surface, altering how easily surfaces are penetrated or spread.

Common Pitfalls and Precision Points

Cohesion and adhesion are not opposites; they are distinct interactions that often work together in the same system.

Surface tension is a consequence of cohesion, but it is specifically about behaviour at the surface of a liquid, not within the bulk.

These properties depend on hydrogen bonding among water molecules; altering temperature or solute composition can change the strength and organisation of the hydrogen-bond network.

FAQ

Ions interact with water molecules and can reorganise hydrogen-bond networks.

Depending on concentration and ion type, surface tension may increase, and wetting behaviour at surfaces can change.

Beading occurs on less polar, more hydrophobic surfaces that reduce adhesion.

Lower adhesion relative to cohesion favours rounded droplets and limited spreading.

A meniscus is the curved surface of a liquid in a narrow container caused by adhesion and cohesion.

Its shape influences capillary movement and how fluids contact tube walls.

They position hydrophilic parts in water and hydrophobic parts away from it, disrupting cohesive interactions at the surface.

This can make surfaces easier to spread across or penetrate.

Smaller diameters increase the surface-area-to-volume ratio, so adhesive interactions with the walls have a larger influence.

Cohesion then pulls additional water along, sustaining movement as a column.

Practice Questions

State what causes cohesion in water and give one biological importance. (2 marks)

Cohesion is caused by hydrogen bonds between water molecules. (1)

One correct importance (e.g., maintains continuous water columns in narrow tubes / helps droplet formation / supports movement of water in small channels). (1)

Explain how hydrogen bonding in water leads to adhesion and surface tension, and describe two biological processes that rely on these properties. (6 marks)

Adhesion explained as attraction between water and other polar/charged surfaces due to hydrogen bonding/attractive interactions. (1)

Clear link to hydrogen bonding enabling water to interact with hydrophilic surfaces. (1)

Surface tension explained as net inward pull at the surface due to cohesive hydrogen bonding. (1)

Biological process relying on adhesion (e.g., wetting of tissues or capillary action) described. (1)

Biological process relying on cohesion/surface tension (e.g., support at air–water interface or stability of surface films/droplets) described. (1)

Explanation connects property to function rather than just naming (cause-and-effect stated). (1)