AP Syllabus focus:

‘Pluralist democracy emphasizes group-based activism by nongovernmental interests that seek to influence political decision making through advocacy, lobbying, and coalition-building.’

Pluralist democracy explains how organized groups, not just individual voters, shape policy in the United States. It focuses on competition among interests, unequal resources, and the ways groups try to translate preferences into government action.

Core Idea of Pluralist Democracy

Pluralist democracy treats policymaking as a product of group-based activism rather than a simple “majority rules” outcome. In practice, people often pursue political goals by joining nongovernmental interests (outside of formal government) that represent shared values, occupations, identities, or policy priorities.

Pluralist democracy: A model of democracy in which politics is mainly a competition among organized groups that seek to influence government decisions through pressure, bargaining, and participation.

Pluralism assumes that if many groups can organize and compete, government will be more responsive across many issues, because officials face pressures from multiple sides.

Nongovernmental Interests and Why They Mobilize

What counts as “nongovernmental interests”?

Pluralism focuses on groups operating outside government institutions, such as interest groups, advocacy organisations, professional associations, labour unions, and public-interest movements. These groups try to shape outcomes by targeting the institutions that write, implement, and interpret policy.

Why groups form and act politically

Group mobilisation is driven by:

Shared policy goals (e.g., environmental protection, business regulation, civil liberties)

Protection of economic interests (industries, professions, workers)

Identity and values (religious, racial/ethnic, ideological communities)

Perceived threats or opportunities (a bill moving in Congress, a new court case, an agency rule)

The Main Tools: Advocacy, Lobbying, and Coalition-Building

Pluralist democracy in the AP framework highlights three core strategies used to influence political decision making.

Advocacy

Advocacy is public-facing persuasion designed to shift opinions and priorities. Common advocacy tactics include:

Public campaigns (messages, media outreach, community events)

Grassroots mobilisation (encouraging members to contact officials)

Research and framing (reports, data, narratives that define a problem and solution)

Advocacy often tries to shape what government treats as important—especially which issues get attention at all.

Lobbying

Lobbying is direct communication with policymakers and their staffs to influence specific decisions. In pluralist politics, lobbying can target:

Legislatures (bill language, committee votes, leadership agendas)

Executive agencies (regulations, enforcement priorities, rulemaking comments)

State and local officials (implementation choices, contracts, ordinances)

Lobbying is most effective when groups can supply what officials need: expertise, constituent signals, political support, or policy details.

Coalition-building

Coalition-building brings multiple groups together to increase influence. Coalitions matter because they:

Combine membership size, funding, expertise, and credibility

Signal broad support to elected officials

Share tasks (research, lobbying, outreach) to sustain campaigns over time

Coalitions can be temporary (focused on one bill) or long-term (aligned on a wider policy agenda).

How Group Competition Shapes Policy Outcomes

Pluralist democracy expects political outcomes to reflect bargaining and compromise among competing groups. Key dynamics include:

Multiple points of access: groups can pressure different institutions (committees, agencies, courts) depending on where decisions are being made.

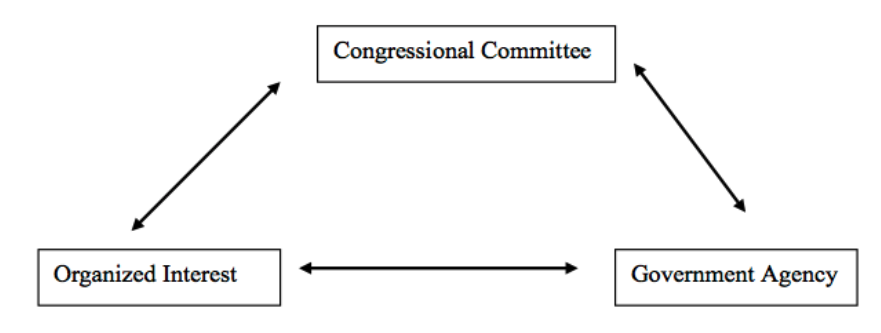

This diagram illustrates an “iron triangle,” a stable policy network linking a congressional committee, an executive agency, and an organized interest. The two-way arrows highlight reciprocal benefits (information, oversight, resources, and policy support) that can make certain policy areas less open to broad competition. In pluralist terms, it helps explain why access and ongoing relationships can matter as much as elections in shaping policy. Source

Policy specialisation: many issues are technical, giving organised groups advantages in providing information and drafting proposals.

Unequal resources: some interests have more money, organisation, or expertise, which can amplify their influence—even in a system with many competing voices.

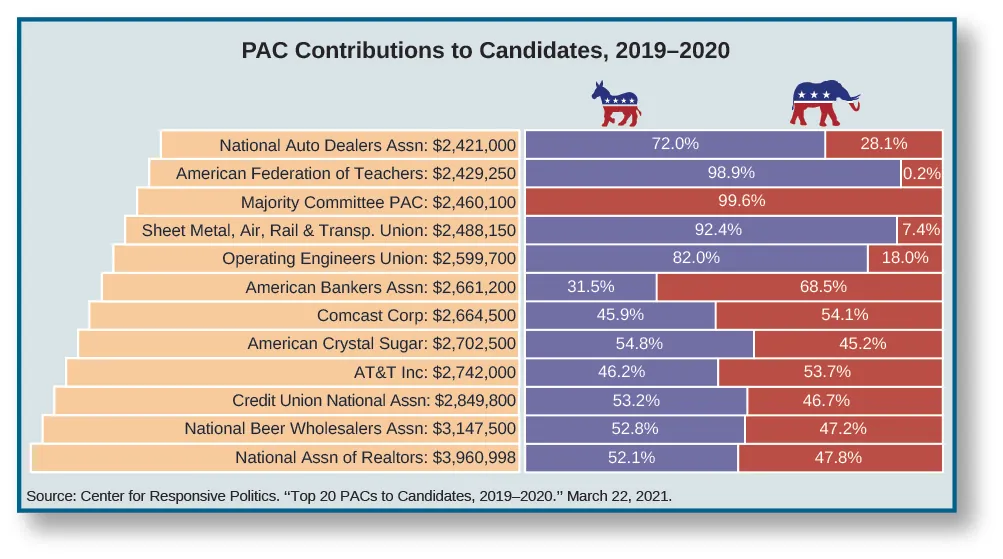

This figure summarizes PAC contributions to candidates (2019–2020), breaking down totals and partisan shares across major organizations. It provides an empirical snapshot of how financial resources—an important form of political capacity—enter pluralist competition. Use it to connect the abstract idea of resource inequality to a measurable input that can shape access and agenda-setting. Source

Pluralism therefore highlights both responsiveness (many interests can be represented) and potential bias (well-resourced groups may dominate certain policy arenas).

FAQ

Groups often choose the venue where change is most feasible.

Congress: when legislation is moving or committees are receptive.

Agencies: when rulemaking or enforcement details matter more than statutory change.

They also consider timing, partisanship, and whether technical expertise can sway outcomes.

Insider strategies work through direct access:

meetings with staff, drafting proposals, testifying, regulatory comments.

Outsider strategies build pressure from the public:

demonstrations, media campaigns, member call-ins, boycott threats.

Many groups blend both, switching when political conditions change.

Coalitions can fail due to:

disagreements over policy details or sequencing

competition for credit, funding, or membership

conflicting long-term priorities beyond the immediate issue

Managing coalition discipline often requires clear leadership and a narrow shared agenda.

Common approaches include:

registration and disclosure requirements

limits on gifts and revolving-door employment

transparency for campaign spending and issue advertising

Regulation aims to inform the public and deter corruption while preserving petitioning and representation.

Digital tools can reduce mobilisation costs:

rapid fundraising, targeted messaging, online petitions, and peer-to-peer outreach

However, online attention can be short-lived, and algorithmic amplification may favour polarising content, affecting which groups gain visibility and sustained influence.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks) Define pluralist democracy and identify two methods by which nongovernmental groups can influence political decision making.

1 mark: Accurate definition of pluralist democracy (competition among organised groups influencing government).

1 mark: Identifies one valid method (e.g., advocacy, lobbying, coalition-building).

1 mark: Identifies a second valid method (must be distinct from the first).

Question 2 (4–6 marks) Explain how advocacy, lobbying, and coalition-building can each affect policy outcomes in a pluralist democracy. In your answer, discuss one reason group influence may be unequal.

1–2 marks: Explains advocacy as public persuasion/grassroots activity shaping agendas or opinion.

1–2 marks: Explains lobbying as direct contact with policymakers/agencies affecting bills or rules.

1 mark: Explains coalition-building as groups combining resources to increase leverage/credibility.

1 mark: Explains unequal influence (e.g., differing resources, expertise, access, membership size).