AP Syllabus focus:

‘Participatory, pluralist, and elite models of representative democracy continue to appear in modern institutions and political behavior, shaping how citizens and groups influence government.’

Modern U.S. politics mixes broad citizen participation, organised group influence, and leadership by a comparatively small set of highly engaged actors. These three democracy models help explain how institutions actually operate and whose preferences shape policy.

Core idea: three models operating at once

Democracy model: A framework for describing who holds political influence and how political decisions are shaped within a representative system.

In practice, U.S. institutions rarely reflect only one model. Instead, participatory, pluralist, and elite patterns appear simultaneously across elections, parties, interest groups, media, and policymaking venues.

Participatory democracy today: citizen-centred influence

Where it shows up in institutions

Elections: voting, volunteering, and local mobilisation aimed at making officials responsive to broad public preferences.

Political parties: mass membership activities such as canvassing, attending meetings, and participating in party primaries and caucuses.

Public consultation: town halls, public comment periods, and direct contact with representatives (calls, emails, constituent meetings).

Behavioural indicators

Turnout levels and gaps (by age, education, and income) signal how evenly participation is distributed.

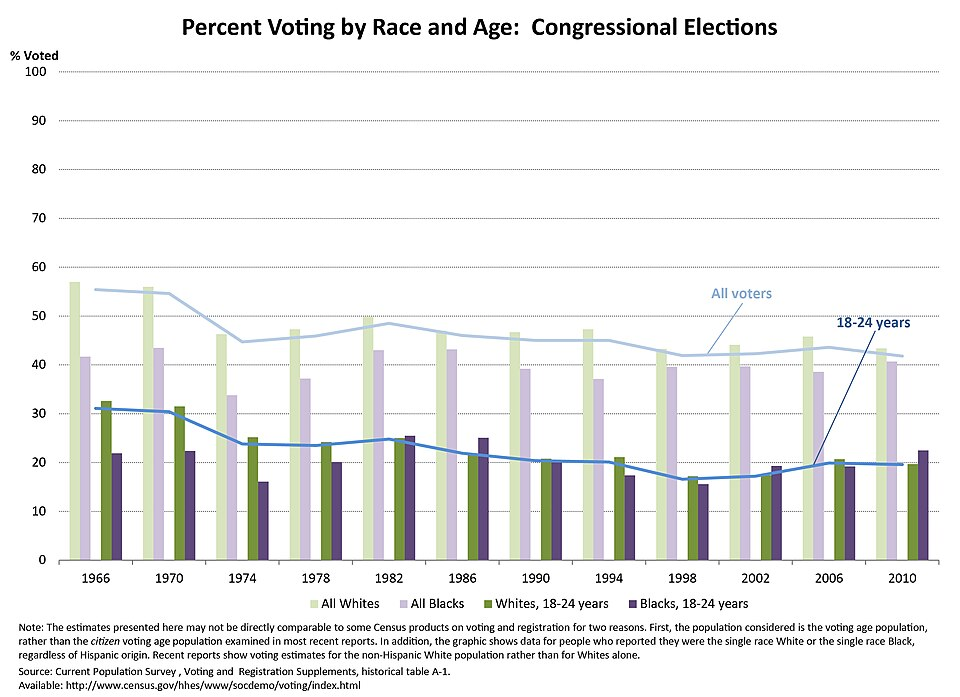

This U.S. Census Bureau chart tracks turnout in U.S. congressional elections over time, broken down by age and race. It visually reinforces that participation is not evenly distributed across demographic groups, which can shape whose preferences elected officials hear most consistently. In participatory-democracy terms, persistent turnout gaps can weaken broad responsiveness even when elections are formally open to all. Source

Grassroots activism: protests, petitioning, community organising, and peer-to-peer mobilisation.

Small-dollar fundraising and volunteer networks can increase participation by lowering barriers to entry.

Limits within the model

Participatory influence is strongest when participation is broad and sustained; it weakens when political efficacy is low, when participation is unequal, or when electoral choices feel uncompetitive.

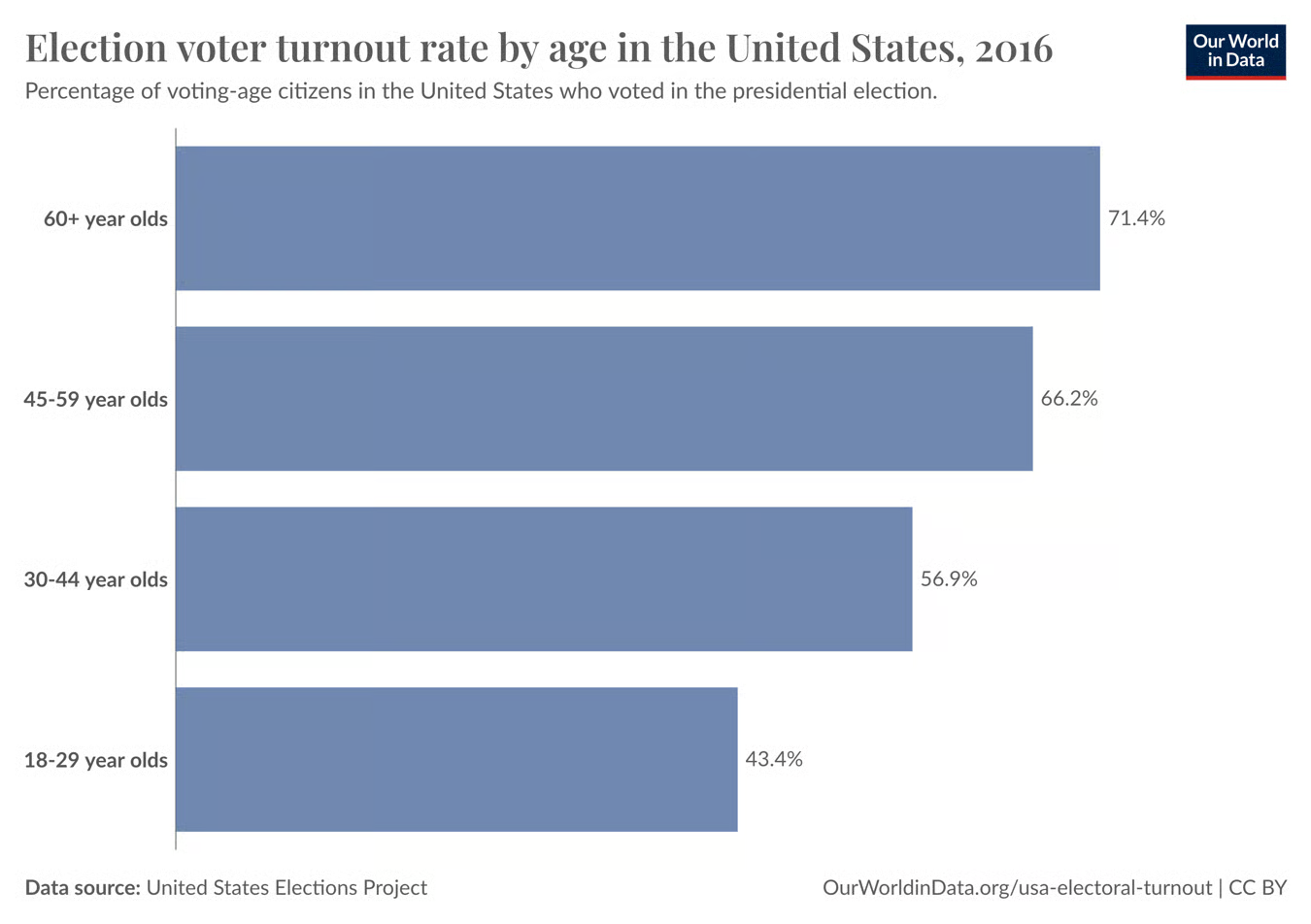

This bar chart (built from U.S. Elections Project/CPS-based estimates) compares voter turnout across age groups in a recent presidential-election context, highlighting a substantial participation gap between younger and older eligible voters. The visual supports the idea that participatory influence depends not just on formal rights but on who actually shows up. When turnout is systematically lower in some groups, policymakers may face weaker electoral incentives to prioritize those groups’ concerns. Source

Pluralist democracy today: groups and organised competition

Where it shows up in institutions

Interest groups and lobbying: policy influence through direct lobbying, testimony, and coalition-building around shared goals.

Congressional committees and executive agencies: groups target specialised venues where technical expertise and access can shape drafting, oversight, and rulemaking.

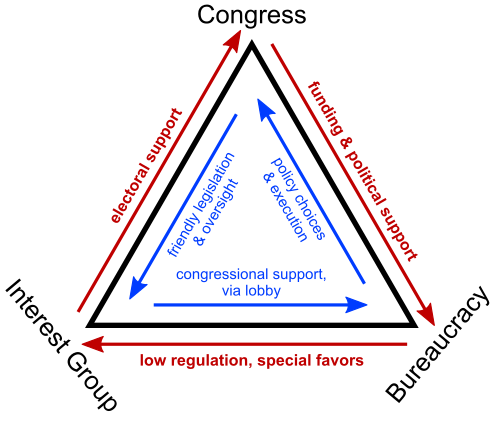

This diagram illustrates an “iron triangle,” showing the mutually reinforcing relationships among congressional committees, executive agencies, and interest groups. It helps explain how organized interests can gain influence through information, access, and political support within specialized policymaking venues. The model is often used to connect pluralist competition to concerns about unequal access and concentrated influence. Source

Courts: groups support litigation and file amicus curiae briefs to influence legal interpretation.

Interest group: An organised set of individuals or organisations that seeks to influence public policy without running candidates for office.

Behavioural indicators

Joining membership organisations, donating to advocacy groups, signing onto campaigns, and engaging in targeted issue activism.

“Inside” strategies (lobbying, expertise, relationships) alongside “outside” strategies (media campaigns, voter mobilisation).

What pluralism predicts

Policy is often shaped by competition among organised interests, especially in complex policy areas where information and sustained engagement matter.

Influence depends on resources and organisation, which means pluralism can be highly active while still unequal.

Elite democracy today: concentrated influence and unequal participation

Where it shows up in institutions

Candidate recruitment and leadership selection: party leaders, major donors, and experienced networks can shape who runs and who becomes viable.

Campaign finance and political consulting: professionalised campaigning can privilege actors with money, data, and strategic expertise.

Agenda-setting: policy priorities may reflect the preferences of elected officials, party leadership, donors, and well-resourced organisations more than mass opinion.

Behavioural indicators

Low-information participation (or nonparticipation) alongside intense engagement by a smaller set of donors, activists, and policy professionals.

Reliance on elite cues: voters taking positions from trusted leaders, partisan figures, or prominent organisations rather than detailed policy knowledge.

What elite theory emphasises

Even with free elections, influence may be unevenly distributed if participation is unequal and if institutions reward resources, expertise, and access.

How to apply the models to contemporary U.S. politics

Interpreting the same institution through different lenses

Elections can look participatory (high turnout and mobilisation), pluralist (groups mobilising voters around issues), or elite (fundraising networks and strategic professionals shaping outcomes).

Policy outcomes can reflect pluralist bargaining among groups, elite-driven agenda control, or participatory pressure when public engagement becomes intense and sustained.

Key comparison questions students should ask

Who participates: broad publics, organised groups, or a smaller set of highly engaged actors?

Which resources matter most: votes, organisation, money, expertise, or access?

Which institutions are most responsive: elections, legislatures, agencies, or courts?

FAQ

Common measures include turnout rates, donation patterns, lobbying activity, and who gets access to decision-makers.

Researchers also compare public opinion with policy outputs to assess responsiveness, and examine whether influence is broad-based or concentrated.

Pluralism focuses on competition among many organised interests.

The interpretation shifts towards elite when a small number of groups dominate access due to exceptional resources, long-term networks, or privileged entry into key venues.

Experts can support pluralism by providing information that multiple groups use to compete effectively.

They can also support elite dynamics when technical expertise becomes a barrier that limits meaningful participation to insiders.

Social media can lower participation costs (organising, fundraising, awareness), strengthening participatory pathways.

At the same time, algorithms, influencer politics, and targeted advertising can amplify elite agenda-setting and resource advantages.

Activism may be intense but unevenly distributed, episodic, or focused on issues with limited institutional access.

Policy change can still depend on gatekeepers, procedural control, and sustained resources, which can preserve elite advantages even amid visible participation.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Identify one contemporary political behaviour consistent with the participatory model of democracy and briefly explain why it fits that model.

1 mark: Identifies a valid behaviour (e.g., voting, volunteering, attending a town hall, grassroots protesting).

1 mark: Explains it as broad citizen participation aimed at influencing government decisions/elections.

(6 marks) Compare how pluralist and elite models of democracy explain influence over public policy in the United States. In your answer, refer to at least one political institution or arena.

2 marks: Accurate explanation of pluralist influence (competition among organised interests; lobbying/coalitions; multiple organised voices).

2 marks: Accurate explanation of elite influence (policy shaped disproportionately by a smaller, resource-rich or professionally connected set; agenda-setting/campaign finance/expertise).

1 mark: Applies both models to a specific institution/arena (e.g., Congress, agencies, courts, elections, party leadership).

1 mark: Provides a clear comparison (similarity/difference) about who has influence and why.