AP Syllabus focus:

‘Participatory democracy emphasizes broad participation in politics and civil society; citizens engage directly through voting, activism, and community involvement.’

Participatory democracy highlights the idea that self-government works best when many people take part, not just by choosing leaders, but by shaping public life through civic action.

Core idea: broad participation

Participatory democracy is a model of representative government that stresses widespread, ongoing involvement by ordinary citizens in politics and civil society.

Participatory democracy: A democratic approach that emphasises broad, direct citizen involvement in political processes and civic life beyond occasional elections.

This model assumes participation is both a right and a civic responsibility, and that a healthier democracy results when engagement is frequent, informed, and locally grounded.

Politics and civil society

Participatory democracy spans two connected arenas:

Politics: activities aimed at influencing government decisions and leadership selection.

Civil society: voluntary community spaces outside government (e.g., associations, neighbourhood groups, service organisations) where people practise cooperation and public problem-solving.

How citizens participate

The specification emphasises participation through voting, activism, and community involvement.

This “Spectrum of Public Participation” diagram summarizes five increasing levels of public involvement in government decision-making: Inform, Consult, Involve, Collaborate, and Empower. It is useful for classifying real-world civic actions (like public comment, petitioning, or co-designing policy) by how much public impact they are designed to have. Source

These overlap in practice and often reinforce each other.

Voting and electoral engagement

Voting is the most universal participatory act because it directly connects citizens to representation and legitimacy.

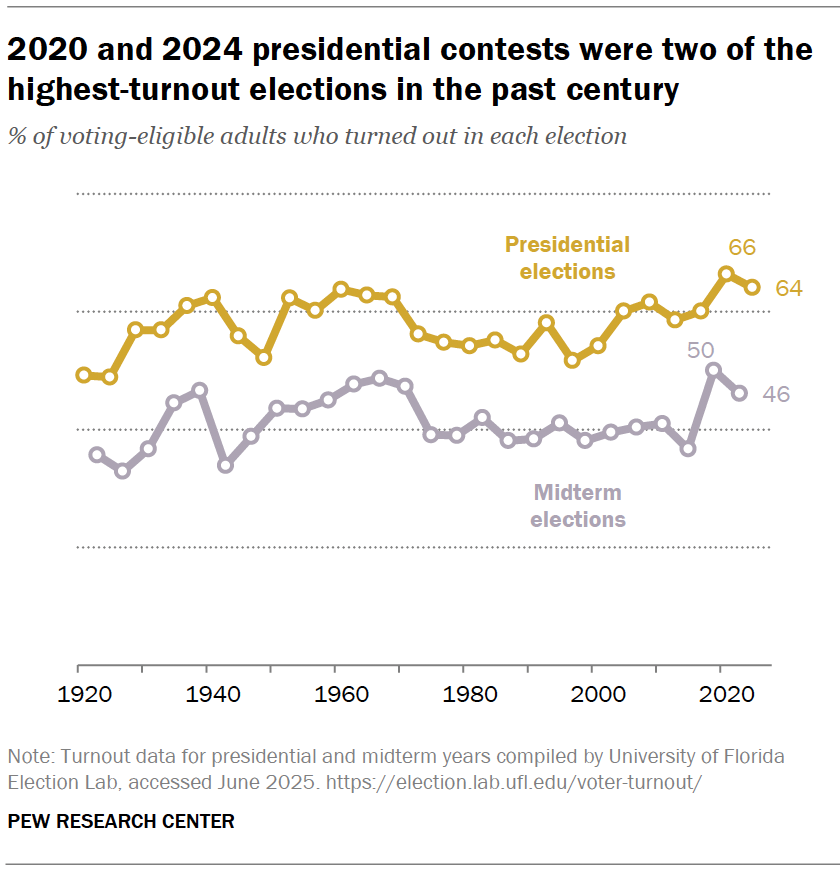

This Pew Research Center line chart compares U.S. turnout rates in presidential elections versus midterm elections across many decades (as a share of voting-eligible adults). The visual highlights a recurring pattern: presidential years consistently draw broader participation than midterms, which matters for how representative and responsive elected officials may be. Source

Voting in elections (local, state, federal) selects public officials and signals public priorities.

Participating in primaries and caucuses helps determine party nominees, often in lower-turnout settings where individual influence can be larger.

Ballot measures (where available) allow citizens to decide specific policies directly, linking public preferences to policy outcomes.

Activism and advocacy

Activism involves organised efforts to draw attention to issues and pressure decision makers. It can be institutional or disruptive, but remains participatory when it aims to widen involvement.

Protesting and demonstrating to publicise concerns and build solidarity.

Petitioning officials or agencies to adopt, change, or enforce policies.

Campaign volunteering (door-knocking, phone-banking, voter registration) to mobilise others.

Attending public meetings (school boards, city councils) to provide comment, demand accountability, or shape implementation.

Community involvement and civic life

Participatory democracy also depends on sustained local engagement that builds skills and social trust.

Community problem-solving (neighbourhood safety initiatives, mutual aid, local environmental projects).

Joining civic organisations that coordinate service, deliberation, and leadership development.

Public deliberation in forums that prioritise discussion, listening, and compromise, helping translate values into workable policy demands.

Why participatory democracy matters

Broad participation is valued because it can:

Improve responsiveness: officials anticipate electoral and public reactions when citizens are attentive and active.

Build civic capacity: participation develops political knowledge, leadership, and cooperation skills.

Increase legitimacy: outcomes are more likely to be accepted when people believe they had meaningful opportunities to influence decisions.

Participatory democracy also shapes expectations: citizens are not merely spectators but contributors to public life, especially in local contexts where community involvement is most feasible.

Limits and tensions within participation

Even when the ideal is broad participation, real-world engagement can be uneven.

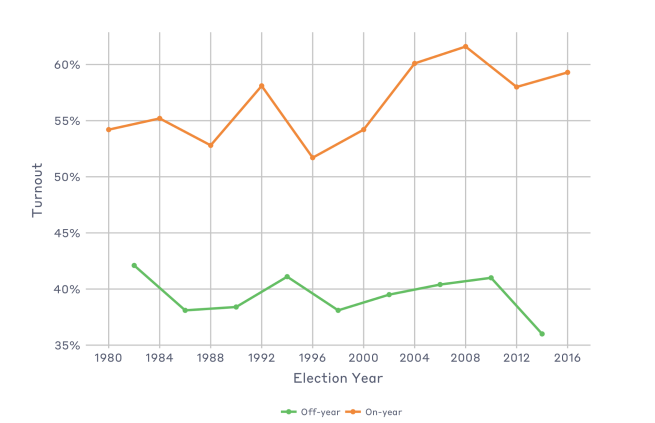

This MIT Election Lab line graph plots nationwide turnout in federal elections over time, separating presidential ‘on-year’ elections from lower-turnout ‘off-year’ elections. The visualization helps explain why participatory democracy can be uneven in practice: institutional timing and election context strongly affect how many citizens participate. Source

Time, money, and information affect who participates most, potentially privileging the well-resourced.

Barriers to voting (registration rules, work schedules, limited polling access) can reduce turnout and skew representation.

Political efficacy—belief that participation matters—can rise or fall depending on whether institutions seem responsive.

Collective action problems can discourage involvement when individuals feel their contribution is too small to matter.

Participatory democracy therefore focuses not only on encouraging engagement, but on whether institutions and civic organisations make participation realistic and consequential for ordinary people.

FAQ

It lowers the cost of mobilisation and speeds up agenda-setting.

It can also encourage “clicktivism,” where visible support does not translate into sustained participation, and it can amplify misinformation that distorts engagement.

Local government often provides the most accessible entry points.

Meetings are easier to attend, issues are tangible (schools, policing, zoning), and a small number of participants can have a proportionally larger impact on decisions.

Common measures include volunteering, meeting attendance, contacting officials, protest participation, group membership, and civic service.

Some studies also track “civic skills” (public speaking, organising) as indicators of participatory capacity.

Examples include:

Automatic or same-day voter registration

Expanded early voting and postal voting

Civic education and youth engagement programmes

Meeting accessibility reforms (timing, translation, childcare, remote access)

It can increase participation rates and equality of turnout.

However, critics argue compelled participation may weaken the link between engagement and genuine civic motivation, shifting focus from active citizenship to compliance.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (3 marks) Explain what participatory democracy emphasises in the United States and identify one way citizens engage directly.

1 mark: States that participatory democracy emphasises broad participation in politics and civil society.

1 mark: Identifies a direct form of engagement (e.g., voting, activism, community involvement).

1 mark: Briefly explains how the identified action involves citizens directly (e.g., voting selects representatives; activism pressures decision makers; community involvement addresses local problems).

Question 2 (6 marks) Using the participatory democracy model, analyse how citizen involvement beyond voting can influence political outcomes in the United States. In your answer, refer to activism and community involvement.

1 mark: Links participatory democracy to broad, ongoing citizen participation beyond elections.

2 marks: Explains activism as a pathway to influence (e.g., protests/petitions/mobilisation shaping agendas, signalling salience, pressuring officials).

2 marks: Explains community involvement as a pathway to influence (e.g., local meetings, civic groups, problem-solving affecting implementation and local policy priorities).

1 mark: Connects these activities to political outcomes (e.g., agenda-setting, responsiveness, legitimacy, policy adoption or enforcement).