AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Constitution and the debate between Federalist No. 10 and Brutus No. 1 reflect tension between broad participation and more filtered participation associated with pluralist and elite models.’

These two ratification-era essays frame a core dilemma of American constitutional design: how to preserve liberty and responsive government while preventing instability, oppression, or capture by powerful interests.

Context: Why These Papers Matter

Federalist No. 10 (James Madison) and Brutus No. 1 (an Anti-Federalist writer) were persuasive arguments aimed at the public during the ratification debate.

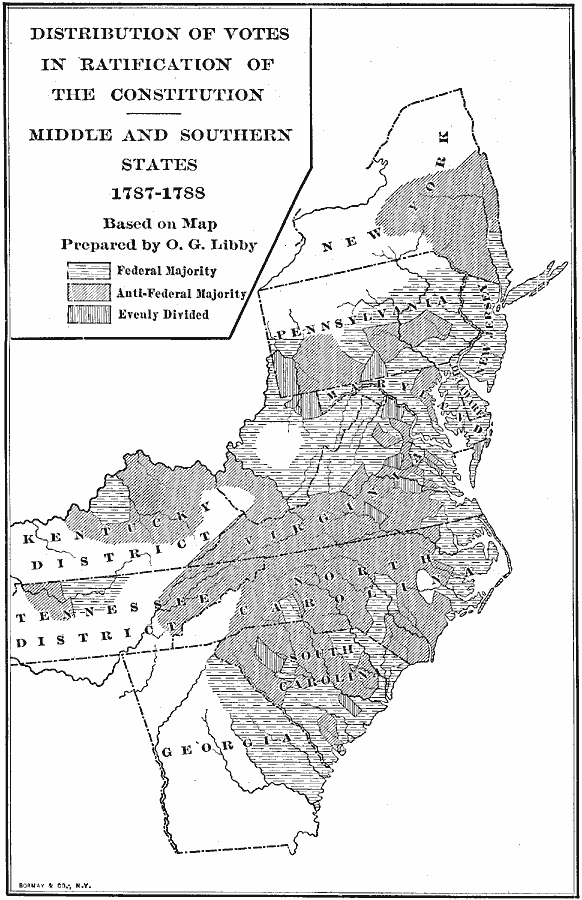

Map showing regional patterns of Federalist and Anti-Federalist majorities during Constitution ratification voting (1787–1788). Use it to connect the essays’ arguments to real political cleavages: areas worried about distant power often aligned with Anti-Federalist skepticism, while other regions favored a stronger national framework. Source

Both focus on how a republic should handle disagreement and competing interests, but they disagree sharply about whether a large national republic protects or endangers self-government.

Key Concepts Driving the Dispute

Madison and Brutus start from the same problem: political conflict is inevitable because citizens hold different interests and values. They diverge on whether constitutional structure can channel conflict safely.

Faction: a group of citizens, majority or minority, united by a common interest or passion that may harm others’ rights or the public good.

Madison treats factions as unavoidable and designs around them; Brutus fears certain factions will become dominant under the proposed Constitution.

Federalist No. 10 (Madison): Control the Effects of Faction

Central claim

A large republic is better than a small one at limiting the damage factions can cause, especially when the system relies on representation rather than direct rule.

How a large republic helps (Madison’s logic)

More interests and viewpoints exist in a large society, making it harder for any single faction to form a durable majority.

Representation “refines and enlarges” public views: elected officials are expected to deliberate and resist sudden popular impulses.

A wider sphere makes it harder for demagogues to coordinate majority oppression across many districts and communities.

Link to “filtered participation”

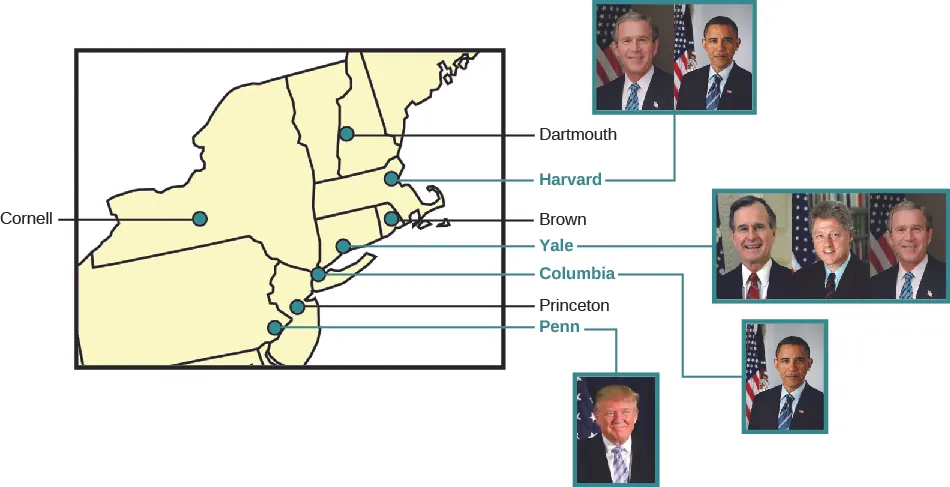

Figure illustrating an elite-theory indicator: presidents’ educational ties to Ivy League institutions, mapped and labeled. It provides a concrete example of how “filters” (like credentialed pipelines and elite networks) can shape who governs, reinforcing the notes’ contrast between broad participation and mediated influence. Source

Madison accepts popular rule in principle but expects it to work through institutional filters:

voters choose representatives rather than deciding policy directly

a broader electorate and multiple constituencies dilute extreme demands This aligns with the idea that participation is real but mediated by structures that slow and shape public influence.

Brutus No. 1: A Large Republic Will Undermine Self-Government

Central claim

The proposed Constitution creates a national government too distant from ordinary people; a large republic will not control factions but will instead produce consolidated power and weak accountability.

Major arguments (Brutus’s logic)

Representation becomes less meaningful as the polity grows: representatives are farther from constituents and less likely to understand local needs.

A powerful national government encourages an elite governing class: well-connected, wealthy, and professionally political figures can dominate elections and policy.

Diverse interests do not necessarily “cancel out”; instead, organised and resourced groups can coordinate influence more effectively than scattered citizens.

Over time, national power tends to expand, leaving states and local communities with reduced authority and citizens with fewer practical ways to control policy.

Link to “broad participation”

Brutus emphasises that democratic legitimacy requires proximity and responsiveness:

smaller units allow citizens to know candidates and monitor actions

governance closer to the people better reflects popular needs His critique warns that constitutional “filters” can become barriers that reduce effective participation.

Tensions Among Models of Democracy (What the Syllabus Emphasises)

The debate illustrates a persistent tension: should democracy prioritise broad participation or filtered participation to protect stability and rights?

Broad participation impulse

values political equality and responsiveness

prefers decision-making closer to citizens

fears distant institutions enable elite control

Filtered participation impulse (often linked to pluralist/elite dynamics)

assumes competing groups and institutions can check each other

relies on representation and scale to prevent majority tyranny

risks privileging organised, well-funded actors who navigate institutions effectively

What to Watch for in Constitutional Design

When connecting these essays to the Constitution’s logic, focus on how structure can:

disperse power across many constituencies (Madison’s hope)

or distance power from the people (Brutus’s fear) and how that trade-off shapes whose voices are loudest in practice.

FAQ

“Brutus” was a pseudonym, likely used to avoid retaliation and to let arguments stand apart from personal identity in a heated ratification struggle.

It circulated mainly through newspapers and reprints, often read aloud in taverns and meetings, which shaped public discussion beyond formal literacy.

Yes. Many Anti-Federalist proposals favoured looser union features: tighter limits on national taxing/army powers and stronger mechanisms keeping representatives closely tied to local communities.

Because diversity does not prevent coordination by well-resourced groups; modern communication and national fundraising can help concentrated interests act cohesively across a large republic.

They are cited to justify competing readings of republicanism: either deference to institutional “filters” that slow change (Madison) or suspicion of distance and consolidation that dampens popular control (Brutus).

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks) Identify two ways Madison argues a large republic helps limit the harms caused by factions in Federalist No. 10.

1 mark: Explains that a larger republic contains more diverse interests, making majority faction formation harder.

1 mark: Explains that representation/refining public views or the wider sphere makes coordination of oppressive majorities more difficult.

Question 2 (6 marks) Compare the arguments in Federalist No. 10 and Brutus No. 1 about the relationship between the size of the republic and democratic responsiveness. Explain how this debate reflects tension between broad and filtered participation.

1 mark: Madison—large republic dilutes factions through many interests.

1 mark: Madison—representation refines/enlarges public views (a filter).

1 mark: Brutus—large republic weakens accountability/creates distance from constituents.

1 mark: Brutus—risk of elite domination or consolidated national power.

1 mark: Links Brutus to broad participation (local responsiveness).

1 mark: Links Madison to filtered participation (institutional mediation; group competition).