AP Syllabus focus:

‘Federalist and Anti-Federalist disagreements centered on central power and democracy; concerns about individual rights fueled demands for explicit protections, including a bill of rights.’

The ratification debate over the Constitution exposed competing fears: Federalists prioritized effective national governance, while Anti-Federalists worried concentrated power would erode liberty. The dispute produced a pivotal compromise: explicit constitutional rights protections.

Core Disagreements: Power, Democracy, and Liberty

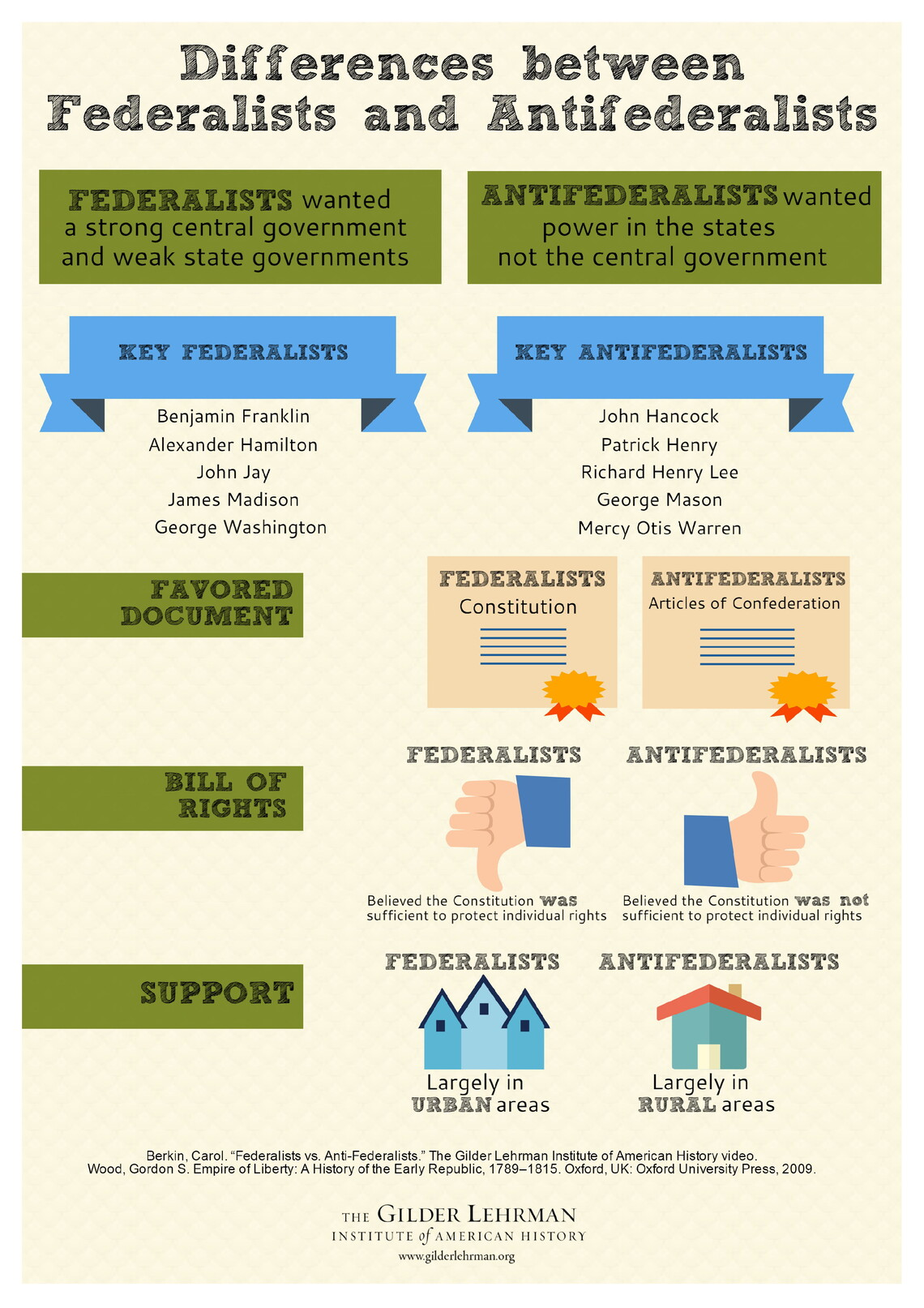

This infographic summarizes the major ratification-era divisions between Federalists and Anti-Federalists, contrasting their views on the strength of the national government, preferred governing framework, and whether a Bill of Rights was necessary. It also highlights representative leaders commonly associated with each side, reinforcing the idea that constitutional design and explicit rights protections were competing strategies for safeguarding liberty. Source

Federalists: Energy in Government, Security for the Republic

Federalists argued the Articles-era experience showed the need for a stronger national government capable of governing a large republic.

Central power: A more capable national structure was necessary to handle collective problems and provide stability.

Democratic design: Federalists defended representation as a way to govern a large nation while avoiding sudden, unstable swings in public opinion.

Liberty through structure: They emphasized that constitutional design—separated institutions, divided authority, and regular elections—could protect freedom without listing every right.

Anti-Federalists: Skepticism of Consolidation and Distant Rule

Anti-Federalists opposed the Constitution as written because they believed it created a consolidated national authority that could overwhelm states and individuals.

Central power as a threat: A distant national government, backed by national taxation and enforcement, could become oppressive.

Democracy concerns: Anti-Federalists argued the new system placed too much decision-making in the hands of elites, weakening direct popular control.

Liberty through explicit limits: They insisted that the Constitution needed clear, enforceable limits to prevent abuses.

Why Individual Rights Became the Flashpoint

The Missing List of Rights

Anti-Federalists highlighted that the Constitution initially lacked an explicit catalogue of individual liberties.

They feared general grants of power (broad authority to govern) could be stretched to justify restrictions on speech, press, religion, or criminal-procedure protections.

They argued that structural constraints alone were not enough; ambitious officials could exploit vague language, emergencies, or national security claims.

Federalists responded that:

Many state constitutions already protected rights, and the federal government was designed as one of limited, delegated powers.

Listing rights could be dangerous if people assumed unlisted rights were unprotected.

Competing Theories of Safeguards

The debate was not simply “rights vs. no rights,” but how liberty is best protected.

Federalist approach: Protect rights primarily through institutional design and limits on enumerated authority.

Anti-Federalist approach: Protect rights through explicit textual guarantees that courts and citizens could invoke against government action.

The Ratification Compromise: Rights Protections as Political Necessity

Conditional Support and the Path to Amendment

As ratification neared, the practical politics of adoption mattered:

Several ratifying conventions proposed amendments as recommended changes, signalling that support depended on additional protections.

Federalists increasingly treated a promise of amendments as the price of securing approval in closely divided states.

This compromise directly reflects the syllabus focus: concerns about individual rights fueled demands for explicit protections, including a bill of rights, even as Federalists and Anti-Federalists continued to disagree about central power and democracy.

The Bill of Rights: What It Was Meant to Do

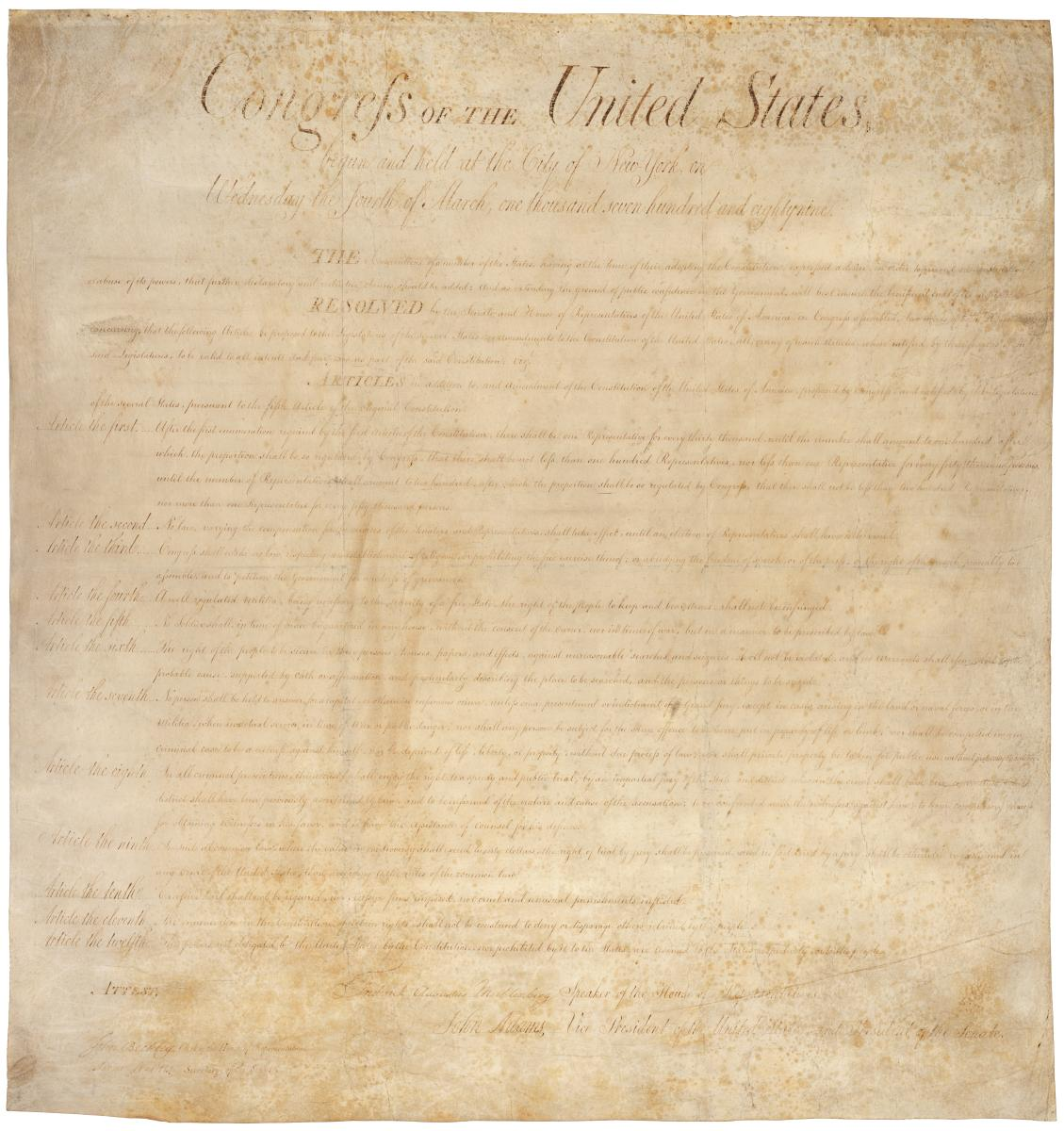

This is a high-resolution image of the U.S. Bill of Rights document held by the National Archives: the enrolled joint resolution passed by the First Congress proposing constitutional amendments. Using the original document helps students connect the abstract idea of “explicit textual guarantees” to the real constitutional language that became the first ten amendments. Source

Bill of Rights: The first ten amendments to the Constitution, adopted to provide explicit protections for individual liberties and to limit potential abuses by the national government.

The Bill of Rights addressed key Anti-Federalist concerns by:

Creating clear prohibitions on certain government actions (for example, restricting Congress in specific liberty-related areas).

Reinforcing procedural fairness in the justice system through protections affecting searches, trials, punishment, and the rights of the accused.

Providing language that citizens and later courts could use to evaluate whether government had exceeded legitimate authority.

Lasting Significance for AP Government

Rights Protections as a Product of Conflict

The Bill of Rights was not an afterthought; it was a direct outcome of the ratification struggle over:

How much power the national government should have

How democratic a large republic could be

How liberty should be protected—by structure, by text, or by both

A Continuing Framework for Debate

The Federalist–Anti-Federalist divide established a recurring pattern in American politics:

Expansions of national capacity often generate renewed demands for clearer rights protections and stricter limits.

Disputes about liberty frequently turn on whether constitutional safeguards should be primarily institutional (design) or explicit (enumerated guarantees).

FAQ

No. Many accepted a national government in principle, but wanted it smaller, closer to the people, and more tightly constrained, with stronger state authority and explicit rights guarantees.

They worried that enumerating some rights could imply others were unprotected, and argued the federal government lacked power to infringe rights unless the Constitution granted it.

Several conventions recommended amendments alongside ratification, signalling conditional support and creating political pressure to add protections quickly after adoption.

They were meant as binding limits, but early impact depended on enforcement and interpretation; their practical force grew as constitutional arguments increasingly relied on textual guarantees.

Common concerns included freedom of expression and religion, protection against arbitrary searches, and criminal-procedure safeguards such as fair trials and limits on excessive punishment.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain one reason Anti-Federalists demanded a bill of rights during ratification.

1 mark: Identifies a valid reason (e.g., fear of an over-powerful national government).

1 mark: Explains how a bill of rights would address that fear (e.g., explicit limits protecting liberties from federal infringement).

(5 marks) Analyse how the Federalist–Anti-Federalist debate over central power and democracy led to the adoption of explicit rights protections.

1 mark: Describes a Federalist argument for stronger national power and/or representative government.

1 mark: Describes an Anti-Federalist concern about centralisation and threats to liberty.

1 mark: Explains why the absence of enumerated rights intensified opposition.

1 mark: Explains the ratification compromise/promise of amendments as necessary to secure support.

1 mark: Links the Bill of Rights to limiting federal power by explicitly protecting liberties.