AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Commerce Clause authorizes national regulation of interstate commerce, but Supreme Court interpretations determine how broadly Congress may use this power.’

The Commerce Clause is a central source of congressional power and a recurring battleground over federalism. Understanding how the Supreme Court has read “commerce” explains major shifts in national policymaking capacity.

Core idea: Congress’s power over interstate commerce

Constitutional basis and key terms

Commerce Clause: Article I, Section 8 power giving Congress authority to regulate commerce “among the several states,” forming a major constitutional basis for federal economic and social regulation.

In practice, disputes arise over whether an activity is interstate (crossing state lines) or intrastate (within one state) but still sufficiently connected to interstate markets to justify federal regulation.

Why interpretation matters

Because the clause’s wording is broad, the Court’s interpretation largely determines:

How far Congress may reach into local economic activity

Whether federal laws preempt or coexist with state rules

The overall balance of power between the national and state governments

Major Supreme Court approaches to “commerce”

Early nationalism: broad federal authority

In the early republic, the Court supported robust federal power to prevent state trade barriers and promote a national economy. A foundational theme is that interstate commerce includes more than just buying and selling goods; it can include commercial activity that crosses borders and requires uniform rules.

Key takeaways from this approach:

Interstate commerce is not limited to the moment of exchange

States cannot use regulation to undermine national commercial unity

Congress has primary authority when interstate trade is affected

New Deal era: the “substantial effects” expansion

During the 1930s–1940s, the Court upheld broad federal regulation to address national economic instability. The key doctrinal move was allowing Congress to regulate:

Activities that are intrastate but have a substantial effect on interstate commerce, especially in the aggregate

This made it constitutionally easier for Congress to regulate wages, production, agriculture, and labor conditions even when the regulated conduct was local, so long as the national economic impact was meaningful.

Civil rights era: commerce power applied to discrimination

In the 1960s, Congress used the Commerce Clause to support civil rights legislation affecting businesses open to the public.

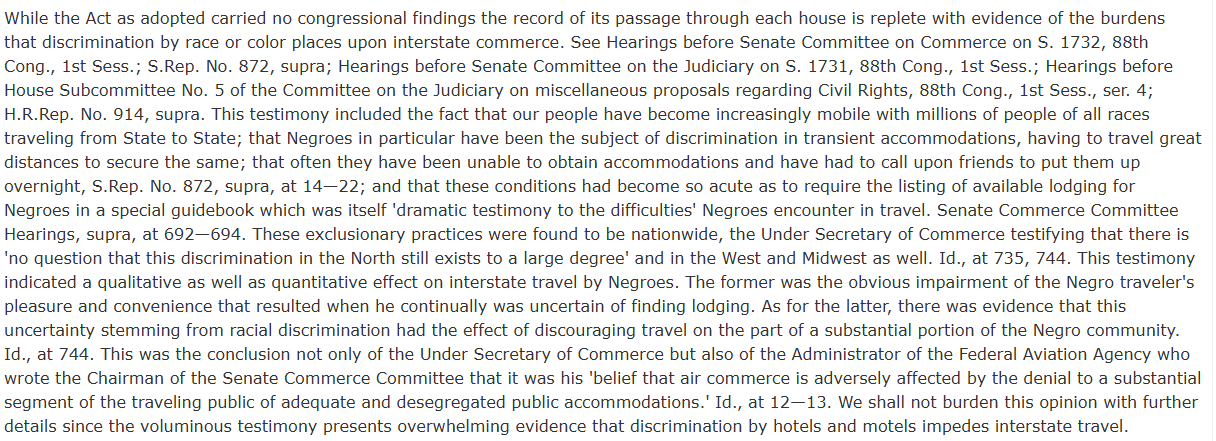

Excerpt from Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States (1964) explaining how a motel’s discriminatory practices were treated as an interference with interstate travel and therefore reachable under Congress’s Commerce Clause power. The passage makes the civil-rights-era logic tangible: local business conduct can be regulated federally when it meaningfully implicates interstate movement and the national marketplace. This supports your point that “commerce” includes channels and instrumentalities of interstate movement, not just buying and selling goods. Source

The Court accepted that discrimination in lodging, dining, and related services could burden interstate travel and the national marketplace.

What students should understand here:

“Commerce” can include the channels and instrumentalities of interstate movement (travel, shipping)

Congress may regulate local business practices when they obstruct interstate economic activity

The clause became a key constitutional foundation for major social policy tied to economic participation

Limits on the Commerce Clause: modern constraints

The “activity” requirement and federalism concerns

From the mid-1990s, the Court signaled that the commerce power is not unlimited. A major limit is that Congress generally must be regulating economic activity or activity closely tied to commerce, not purely noneconomic conduct traditionally handled by states.

Common limiting principles the Court has used:

Distinguishing economic from noneconomic activity

Requiring a clearer link between the regulated activity and interstate commerce

Rejecting arguments that would grant Congress a general “police power” (a power the federal government does not have)

Three categories framework (how laws are evaluated)

In modern doctrine, the Court often analyses whether a federal law fits within one of these categories:

Constitution Annotated (Congress.gov) summary of the Lopez framework, listing the three Commerce Clause categories in an official reference format. This works well as a quick “doctrine box” students can consult when classifying a federal statute. It reinforces the structure behind your bullet list and signals that the categories are now a standard part of modern Commerce Clause analysis. Source

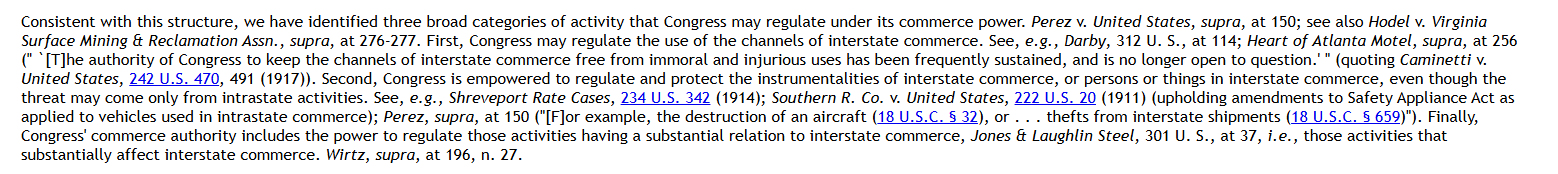

Excerpt from the Supreme Court’s opinion in United States v. Lopez (1995) identifying the three permissible Commerce Clause categories: regulation of channels, regulation of instrumentalities (and persons/things in commerce), and regulation of activities that substantially affect interstate commerce. This primary source is useful for tying your doctrinal bullet list directly to the Court’s own language. It also helps explain why modern cases often turn on whether a statute fits the “substantial effects” category. Source

Regulation of the channels of interstate commerce (e.g., highways, waterways, air routes)

Regulation of the instrumentalities of interstate commerce (e.g., trucks, trains, aircraft) and persons/things in interstate commerce

Regulation of activities that substantially affect interstate commerce (most contested category)

Practical impact on Congress

These interpretations shape how broadly Congress may use the clause:

When the Court reads “substantial effects” broadly, federal policy can reach deep into local markets

When the Court insists on tighter economic connections, states retain more regulatory autonomy

Congress often drafts detailed findings and evidence to show the interstate economic impact of regulated conduct

FAQ

The Court has treated “commerce” as including broader commercial intercourse, such as transportation and movement across state lines.

It may also include local conduct when it meaningfully shapes interstate markets (depending on the Court’s test at the time).

Congress sometimes includes factual findings to document interstate economic effects.

These can support the argument that a regulated activity substantially affects interstate commerce, though the Court may still reject the link if it sees the activity as too noneconomic or too attenuated.

Sometimes, yes. The key question is whether the activity substantially affects interstate commerce, including in the aggregate.

However, modern limits make it harder when the activity is characterised as noneconomic or traditionally state-regulated.

Channels are the pathways of interstate trade (routes and networks).

Instrumentalities are the tools and carriers used in interstate commerce (vehicles and systems), and Congress can protect them even from local threats.

A broad commerce power increases national influence over policy areas states also regulate.

A narrower commerce power preserves state autonomy by limiting federal reach, especially in areas framed as local, noneconomic, or within traditional state responsibility.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Define the Commerce Clause and explain why Supreme Court interpretation affects its scope.

1 mark: Accurate definition of the Commerce Clause (Congress may regulate commerce among the states).

1 mark: Explains that Supreme Court rulings determine how broadly “commerce”/“interstate” is read, shaping the reach of federal laws.

(6 marks) Explain two ways the Supreme Court has interpreted the Commerce Clause differently over time, and for each, describe one consequence for Congress’s policymaking power.

1 mark: Identifies an expansionary interpretation (e.g., “substantial effects”/aggregate impact; broad reading of interstate markets).

1 mark: Explains how that interpretation increases Congress’s regulatory capacity (reaching intrastate activity tied to national markets).

1 mark: Identifies a limiting interpretation (e.g., limits on regulating noneconomic activity; requirement of a tighter nexus to interstate commerce).

1 mark: Explains how that interpretation constrains Congress (reduces ability to legislate in areas traditionally reserved to states).

2 marks: One clear, accurate consequence for each interpretation (must be distinct and linked to Congress’s policymaking reach).