AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Supremacy Clause gives federal law precedence over state law; Supreme Court interpretations help determine when national actions exceed constitutional authority and how conflicts are resolved.’

The Supremacy Clause establishes a hierarchy of law in the federal system. Understanding how courts resolve federal–state conflicts requires knowing when federal law validly preempts state action and when federal officials exceed constitutional limits.

The Supremacy Clause: what it does and what it does not do

Article VI, Clause 2 makes the Constitution, federal statutes, and treaties the “supreme Law of the Land,” binding state judges even when state law conflicts.

Supremacy Clause: The constitutional rule that valid federal law prevails over conflicting state law.

Supremacy does not mean the national government can do anything it wants. Federal law is supreme only when it is constitutional (within the powers granted by the Constitution and consistent with rights protections).

The hierarchy in practice

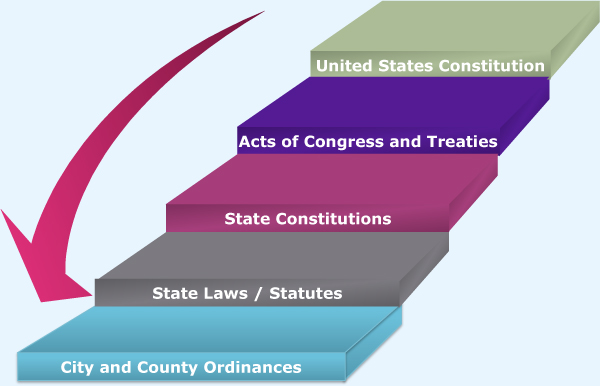

This diagram illustrates the practical hierarchy created by the Supremacy Clause, placing the U.S. Constitution above federal statutes and treaties, which in turn outrank state constitutions, state statutes, and local ordinances. It helps students visualize that federal supremacy operates as a priority rule only when the federal action is valid under the Constitution. Source

If a state constitution conflicts with a valid federal statute, the federal statute controls.

If a federal statute conflicts with the U.S. Constitution, the Constitution controls (the statute can be struck down).

If a state statute conflicts with a valid treaty, the treaty generally controls, though later federal statutes can sometimes supersede earlier treaties (a key complexity in doctrine).

How conflicts are resolved: Supreme Court interpretation

The Supreme Court’s role is central because it interprets:

whether a federal law is valid (constitutional authority and limits), and

whether it displaces state law (preemption).

Judicial review and constitutional boundaries

Courts use judicial review to invalidate:

state laws that interfere with valid federal action, and

federal actions that exceed constitutional authority.

A core idea: the clause answers “which law wins” only after the Court answers “is the federal law valid?”

Preemption: when federal law overrides state law

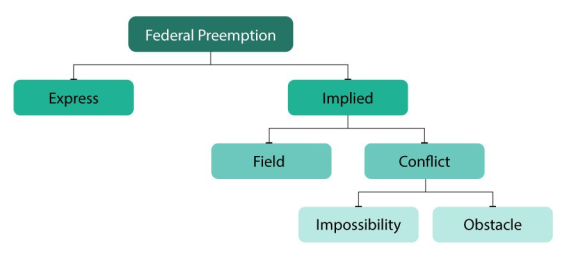

This CRS taxonomy chart organizes federal preemption into the two major categories (express and implied) and then breaks implied preemption into field and conflict preemption, with conflict further divided into impossibility and obstacle preemption. It mirrors the doctrinal structure courts use when deciding whether a federal rule displaces state law under the Supremacy Clause. Source

Preemption describes when federal policy displaces state policy in an area.

Major forms of preemption (how courts think about displacement)

Express preemption: Congress explicitly states that federal law overrides state law in a policy area.

Implied preemption: Congress’s intent is inferred, commonly through:

Field preemption (federal regulation is so pervasive that it “occupies the field”)

Conflict preemption (state law makes it impossible to comply with federal law, or frustrates federal objectives)

Courts look to statutory text, structure, and purpose, and they often weigh federalism concerns (e.g., whether Congress clearly intended to intrude into traditional state domains).

When federal power exceeds limits: common constitutional fault lines

Because federal power is enumerated, the national government must point to constitutional authority for its actions. Supreme Court interpretation determines when federal action goes too far.

Exceeding enumerated powers

Federal laws may be invalidated when Congress relies on a power too broadly (often litigated under the Commerce Clause or other grants of authority). If the Court rules Congress lacks authority, supremacy does not attach because the law is unconstitutional.

Federalism-based limits on implementation

Even when Congress can regulate private conduct, it may face limits on directing states’ machinery:

Anti-commandeering principle: the federal government generally cannot require state legislatures or state executive officials to implement or enforce federal regulatory programs.

Related disputes arise over whether federal funding conditions become unconstitutionally coercive (states must have a real choice).

Practical consequences for federal–state disputes

Supremacy disputes commonly involve:

state “mirror” laws that diverge from federal standards,

state attempts to create additional hurdles to federal policy, or

state efforts to “nullify” federal policy (courts reject unilateral nullification as inconsistent with constitutional supremacy).

Key outcome patterns:

If federal action is valid and preemptive, the state provision is unenforceable to the extent of conflict.

If federal action is beyond constitutional limits, the federal rule is struck down and states may regulate within their reserved authority.

FAQ

State judges must follow the U.S. Constitution and apply controlling Supreme Court precedent.

If constitutionality is unsettled, state courts may address it, but their rulings remain subject to review; they cannot treat their own interpretation as final against later Supreme Court decisions.

Only if the order rests on valid constitutional or statutory authority.

If an executive order conflicts with a statute or exceeds delegated power, courts may block it, and it will not displace state law through supremacy.

Courts sometimes apply a presumption against preemption in areas traditionally regulated by states (e.g., health and safety).

That presumption can be overcome by clear congressional intent, comprehensive federal regulation, or direct conflict.

A court may declare a state law unconstitutional (invalidation), or it may hold the law unenforceable only as applied where it conflicts with federal requirements.

The practical remedy can be narrower than wiping the entire statute.

If an unconstitutional portion can be separated, courts may keep the remainder in force.

Severability depends on statutory design and whether Congress would likely have enacted the remaining parts independently.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Define the Supremacy Clause and state one condition under which federal law is supreme over state law.

1 mark: Accurate definition of the Supremacy Clause (valid federal law prevails over conflicting state law).

1 mark: States a correct condition (e.g., the federal law must be constitutional/within enumerated powers; or there must be a conflict with state law).

(6 marks) Explain how the Supreme Court determines (a) whether a federal statute preempts a state law and (b) when federal action exceeds constitutional limits.

Up to 3 marks (preemption):

1 mark: Identifies express vs implied preemption.

1 mark: Explains field preemption or conflict preemption.

1 mark: Notes Court interpretation of congressional intent/statutory purpose in resolving displacement.

Up to 3 marks (limits):

1 mark: Federal law must be grounded in enumerated constitutional authority to be valid.

1 mark: If beyond authority or unconstitutional, supremacy does not apply and the law can be struck down via judicial review.

1 mark: Mentions a federalism limit on implementation (e.g., anti-commandeering or coercive spending concerns).