AP Syllabus focus:

‘Voting rights have expanded through constitutional amendments that provide legal protections for broader political participation.’

Voting in the United States was not designed as a single, fixed constitutional right. Instead, the Constitution’s rules for elections have been repeatedly revised through amendments that broaden who can participate and limit exclusion.

Constitutional foundations: voting as a regulated practice, not an explicit right

The original Constitution created the basic machinery for elections (offices, terms, and how representation works) but largely left voter qualifications to the states. This meant early access to the ballot could vary widely and could be restricted by wealth, property ownership, sex, race, or other state rules.

Suffrage (franchise): the right to vote in elections.

Key constitutional features that made amendments important later:

Federalism and elections: states administer most election rules, so national expansion of voting access often required national constitutional change.

Structural focus: the Constitution prioritised creating institutions (Congress, presidency) and processes, while leaving many participation rules to politics and state law.

Entrenchment: because the Constitution is supreme law, durable expansions of voting access typically require amendments rather than ordinary statutes alone.

Why amendments are the main tool for expanding voting rights

Amendments matter because they can:

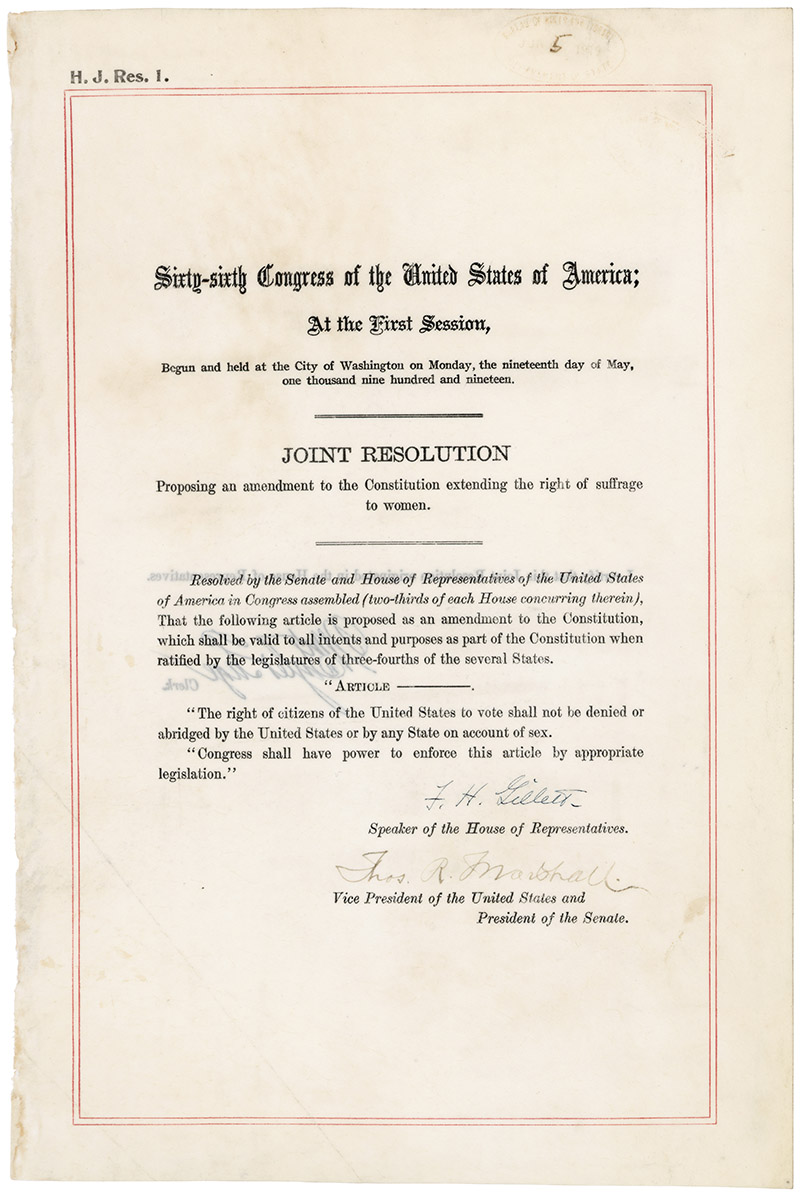

This image shows the joint resolution proposing what became the Nineteenth Amendment, the formal constitutional vehicle used to extend suffrage protections nationwide. It helps students see that voting-rights expansion often occurs through specific Article V text that overrides conflicting state rules and becomes enforceable as supreme law. Source

Override state restrictions by creating nationwide constitutional protections.

Bind all levels of government (state and federal) through the Supremacy Clause.

Provide a stronger basis for judicial enforcement, allowing courts to strike down conflicting state practices.

Signal a national consensus that voting access is a core democratic value.

Constitutional amendment: a formal change to the U.S. Constitution adopted through Article V procedures, carrying the highest legal authority.

Because voting rules were historically decentralised, amendments became the clearest way to nationalise participation standards, especially when some states resisted expanding the electorate.

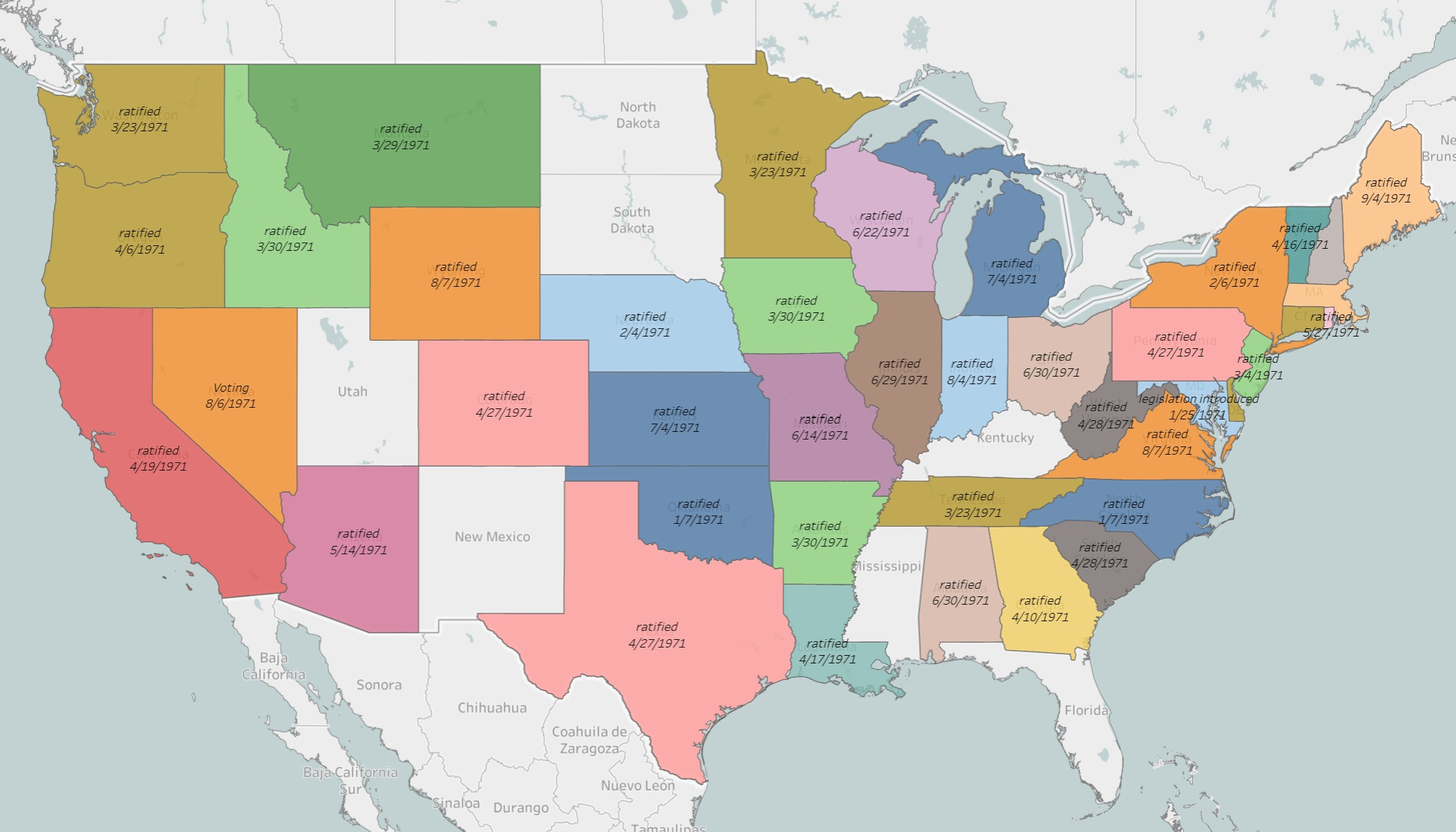

This map depicts state-by-state ratification of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment (1971), showing how a nationwide voting-rights change is implemented through the constitutional ratification process across states. It underscores the federal structure behind amendments: national rules are achieved only after coordinated state approval, producing uniform eligibility standards (here, the voting age of 18). Source

How amendments expand rights: typical constitutional “moves”

Voting-rights amendments tend to expand participation through one or more of these approaches:

1) Anti-discrimination commands

A common strategy is to prohibit denying or abridging voting rights based on a specified status.

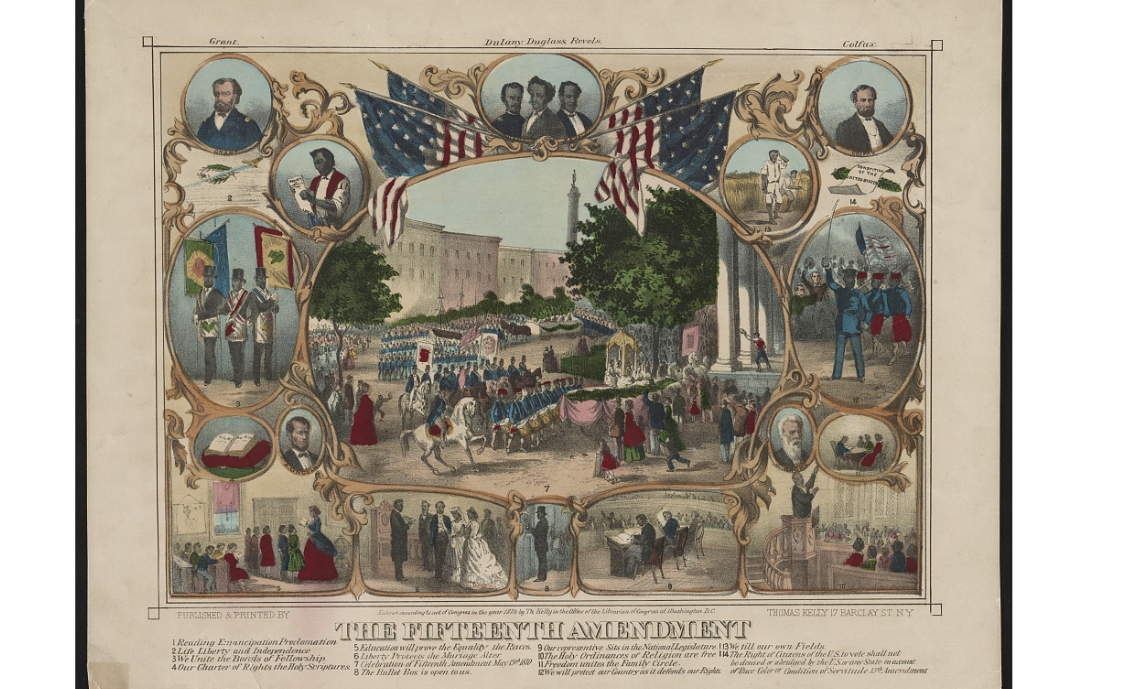

This nineteenth-century print titled “The Fifteenth amendment” illustrates the political meaning of the Fifteenth Amendment by pairing a celebratory scene with vignettes and portraits related to Black civic participation. As a teaching image, it reinforces how some voting-rights amendments are structured as anti-discrimination commands—targeting specific exclusionary criteria and inviting judicial enforcement against conflicting state practices. Source

This approach:

Targets exclusionary criteria that states might use.

Creates a clear constitutional rule courts can apply when reviewing state election laws.

Encourages uniformity while still allowing states to run elections day-to-day.

2) Removing specific barriers to casting a ballot

Another strategy is to eliminate a particular obstacle that blocks access for certain groups. This approach:

Addresses how voting works in practice, not just who is eligible.

Responds to real-world methods of exclusion that developed over time.

Helps equalise participation by reducing “pay-to-vote” or similar burdens.

3) Standardising eligibility across states

Some amendments create a nationwide eligibility baseline. This approach:

Prevents states from maintaining different minimum standards that systematically exclude groups.

Reduces state-by-state disparities in who counts as a full political participant.

Reinforces democratic legitimacy by widening the electorate.

Amendments as “rights plus enforcement”

Voting-rights amendments often do more than announce a principle; they can also empower enforcement. Two mechanisms are especially important for AP Gov analysis:

Judicial interpretation and constitutional review

Once an amendment is adopted, courts interpret:

The scope of the protected voting interest (what counts as denial or abridgment).

The level of scrutiny or intensity of review for challenged laws.

The balance between state authority to regulate elections and constitutional limits on that power.

Court interpretation matters because states may argue that a rule is about election administration, while challengers argue it functions as unconstitutional exclusion.

Congressional enforcement power

Some amendments include or imply that Congress may enforce their guarantees through legislation. This is significant because:

Congress can set national standards for protecting access.

Enforcement laws can target new forms of exclusion that appear after an amendment’s adoption.

The boundary between valid enforcement and overreach is often contested in courts and politics.

Why this approach fits U.S. constitutional design

The amendment-driven expansion of voting rights reflects the Constitution’s broader design:

The system is intentionally difficult to change, so successful amendments typically follow sustained political conflict and coalition-building.

Amendments provide a uniform national rule in an area otherwise shaped by decentralised state control.

Constitutional change can reshape political participation without rewriting the entire electoral system, preserving institutional stability while widening inclusion.

What to be able to do for AP Gov

Students should be able to:

Explain why the original Constitution left voting qualifications largely to states, making later amendments central to expansion.

Describe the general ways amendments expand participation (anti-discrimination rules, barrier removal, eligibility standardisation) without relying on ordinary legislation alone.

Connect amendments to court interpretation and federal enforcement, showing how constitutional protections become real in practice.

FAQ

The framers prioritised creating national institutions and preserving state authority over elections.

Many believed suffrage rules should reflect local conditions, so voter qualifications were treated as a state matter rather than a national entitlement.

Article V requires supermajorities:

Proposal by two-thirds of both houses of Congress (or a convention called by two-thirds of states)

Ratification by three-fourths of states

This structure means broad, cross-regional agreement is usually necessary.

Yes. An amendment can set a participation rule (who cannot be excluded, or what barriers cannot be used) while leaving states free to choose administrative details that comply with the new constitutional limit.

A constitutional protection has higher legal status and is harder to repeal.

A statute is easier to pass and amend, but it must fit within constitutional limits and is more vulnerable to political reversal or being narrowed by courts.

Not automatically. Amendments set constitutional baselines, but:

Implementation often depends on enforcement mechanisms

States may adopt new rules that shift exclusionary effects into administrative details

Courts and Congress play ongoing roles in defining and enforcing the amendment’s reach

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks) Explain one reason constitutional amendments have been important for expanding voting rights in the United States.

1 mark: Identifies that the original Constitution largely left voter qualifications to the states.

1 mark: Explains that amendments create nationwide rules that override conflicting state laws.

1 mark: Develops with a point about durability/supremacy/judicial enforceability (e.g., courts can strike down state restrictions inconsistent with the amended Constitution).

(4–6 marks) Analyse how constitutional amendments can expand political participation while still allowing states to administer elections.

1 mark: Establishes that states run elections day-to-day (registration, polling, administration).

1 mark: Explains that amendments impose constitutional limits on how states may set voter qualifications or access rules.

1 mark: Describes one “expansion mechanism” (e.g., anti-discrimination command OR removal of a barrier OR standardised eligibility).

1 mark: Links amendments to judicial interpretation/review of challenged state rules.

1 mark: Links amendments to congressional enforcement power or national standards derived from constitutional authority.

1 mark: Overall analytical connection showing coexistence: states administer procedures, but amendments set binding participation protections.