AP Syllabus focus:

‘The 14th Amendment granted U.S. citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States, including formerly enslaved people.’

The 14th Amendment (1868) reshaped American democracy by defining national citizenship and limiting state power over individual rights.

Enrolled text of the Fourteenth Amendment as adopted after the Civil War. Seeing the original document helps connect the amendment’s broad guarantees—citizenship, due process, and equal protection—to later constitutional arguments about fair and equal access to political participation. Source

While it did not directly grant voting, it became a central constitutional foundation for expanding and protecting political participation.

What the 14th Amendment Did (and Why It Mattered for Voting)

Citizenship as a baseline for political participation

The 14th Amendment’s first sentence established birthright citizenship, making clear that formerly enslaved people (and their descendants) were U.S. citizens. Citizenship status matters for voting because states historically used legal status to exclude groups from the electorate.

The key constitutional limits on states

The Amendment’s Section 1 contains three major protections that became tools for voting-rights expansion and enforcement against discriminatory state action:

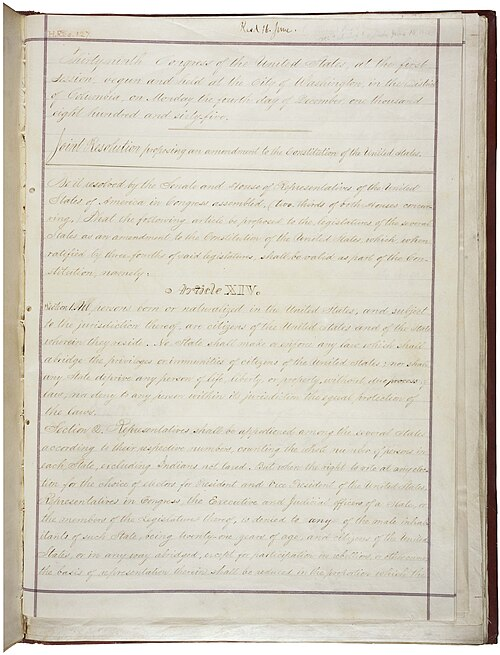

High-resolution scan of the Fourteenth Amendment’s enrolled pages, including the handwritten text and formal layout used for constitutional amendments. This supports close reading of Section 1’s key clauses and emphasizes the amendment as a Reconstruction-era legal instrument later applied to election-law disputes. Source

Citizenship Clause: Establishes national and state citizenship for people born or naturalised in the United States.

Due Process Clause: Bars states from depriving persons of “life, liberty, or property” without fair procedures and lawful justification.

Equal Protection Clause: Requires states to treat similarly situated people alike, limiting arbitrary or discriminatory election rules.

Incorporation: applying federal rights against states

A major voting-rights impact of the 14th Amendment is that it helped apply protections in the Bill of Rights to state governments through the courts.

Incorporation doctrine: The use of the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause to apply most protections in the Bill of Rights to the states.

Incorporation is not a voting right itself, but it strengthens constitutional review of state election practices when they burden protected liberties (for example, political speech and association linked to campaigning and elections).

How the 14th Amendment Expanded Voting Rights Indirectly

Equal protection and the “one person, one vote” principle

The Equal Protection Clause became the constitutional basis for challenging unequal representation and districting schemes that diluted votes. The Supreme Court used equal protection reasoning to require more equal population-based representation, strengthening the practical value of each vote.

Key implications for participation:

Courts could treat severe vote dilution as a constitutional harm.

State election structures became subject to federal judicial review when they undermined political equality.

Due process and fair election administration

The Due Process Clause supports the idea that election administration must meet minimum standards of fairness. While states run elections, the 14th Amendment provides a constitutional backstop against:

Arbitrary or inconsistent application of election rules

Procedures that unfairly burden participation without adequate justification

Section 2: a constitutional signal about voting

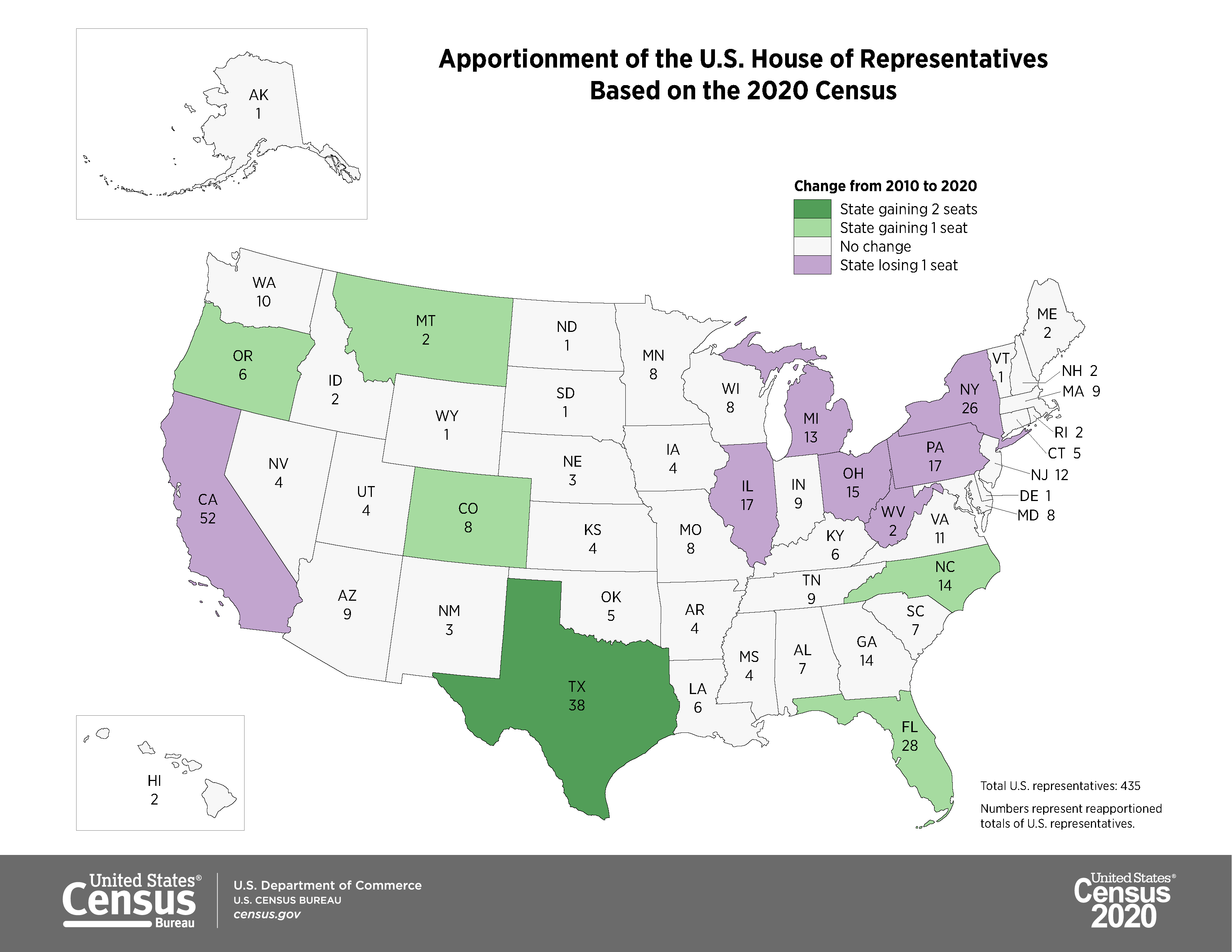

Map visualization of how U.S. House seats shifted among states after the 2020 Census apportionment (compared with 2010). This provides a concrete way to understand why representation formulas—and constitutional provisions about representation—matter for political power and participation. Source

Section 2 ties congressional representation to a state’s voting practices by providing that representation can be reduced if a state denies or abridges voting rights for certain male citizens (as written at the time). Although rarely enforced in practice, it is important because it shows the Reconstruction-era constitutional focus on expanding political participation and discouraging disenfranchisement.

Limits and Controversies

It did not itself guarantee the right to vote

The 14th Amendment made people citizens and constrained discriminatory state action, but it did not create an explicit, universal right to vote. States retained significant power to set election rules, subject to constitutional limits.

“State action” and uneven protection

14th Amendment protections mainly apply to government actions, not purely private conduct. This “state action” requirement has shaped how easily courts can address discrimination connected to elections (for example, when private actors influence access but the state is not directly responsible).

Narrow readings and shifting interpretations

Early Supreme Court interpretations sometimes limited the Amendment’s reach (especially through narrow readings of certain clauses), but later decisions relied heavily on equal protection and due process to scrutinise state election rules. As a result, the 14th Amendment has been a flexible and contested constitutional tool in voting-rights disputes.

FAQ

Yes, through the Citizenship Clause’s “born … in the United States” language, with key debates focusing on the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof”.

Some categories (e.g., children of foreign diplomats) have been treated as exceptions in constitutional practice.

Enforcement would require political will in Congress to reduce a state’s representation.

In practice, Congress has generally relied on other tools (statutes, investigations, and later constitutional developments) rather than invoking Section 2 penalties.

Historically, courts interpreted it narrowly, limiting its use as a broad source of substantive rights.

As a result, most modern rights claims affecting elections have been channelled through Due Process and Equal Protection instead.

A claimant typically must show that the discrimination or burden is attributable to government (state officials, state laws, or state-administered processes).

Private conduct may fall outside the 14th Amendment unless there is substantial government involvement or endorsement.

They are analytically distinct: denial prevents casting a ballot, while dilution reduces the ballot’s practical impact.

Courts have often analysed dilution through Equal Protection frameworks, focusing on whether electoral structures unfairly weaken the political power of certain voters.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks) Explain one way in which the 14th Amendment contributed to the expansion of voting rights.

1 mark: Identifies a relevant feature of the 14th Amendment (e.g., Citizenship Clause, Equal Protection, Due Process).

1 mark: Explains how that feature can be used to challenge state voting restrictions or unequal electoral practices.

1 mark: Applies to voting-rights expansion (e.g., protecting citizens from discriminatory state election laws or supporting equal weighting of votes).

Question 2 (4–6 marks) Assess the extent to which the 14th Amendment expanded voting rights, given that it did not explicitly grant a right to vote.

1–2 marks: Accurate explanation that the 14th Amendment established national citizenship, including formerly enslaved people.

1–2 marks: Explains indirect expansion via Equal Protection and/or Due Process (e.g., constitutional challenges to discriminatory or unequal state election rules; judicial scrutiny).

1 mark: Addresses the limitation that it did not explicitly confer suffrage and states retained control over election rules.

1 mark: Overall judgement about “extent” that weighs indirect protections against the absence of an explicit voting guarantee.