AP Syllabus focus:

‘The 17th Amendment replaced selection of senators by state legislatures with direct election by the people.’

The Seventeenth Amendment (1913) transformed the Senate from a body chosen indirectly by state political elites to one elected by voters.

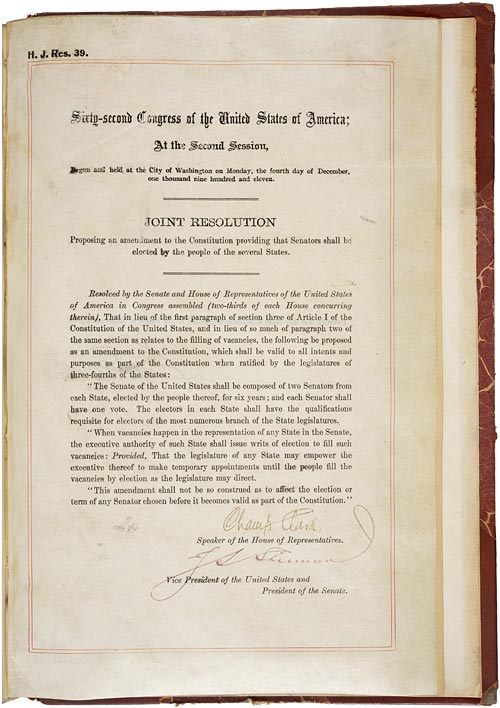

This image shows the National Archives’ enrolled joint resolution associated with the Seventeenth Amendment, the formal document that made direct election of U.S. senators part of the Constitution. Using the original document helps connect the abstract idea of “constitutional change” to the real legal text Congress sent to the states for ratification. Source

This change altered representation, campaign incentives, and the relationship between states and the national government.

Constitutional Change: From Legislative Selection to Popular Election

Before 1913, the Constitution (Article I) had state legislatures choose U.S. senators, an arrangement designed to strengthen state influence in the national government and insulate senators from short-term public pressure.

What the 17th Amendment did

The amendment required that senators be elected by the people of each state, using statewide elections rather than legislative selection.

Direct election: selecting an officeholder through a vote of the eligible electorate, rather than being chosen by an intermediary body (such as a legislature).

In addition to establishing direct election, the amendment also addressed vacancies:

When a Senate seat becomes vacant, a state’s executive authority (governor) issues a writ of election to fill the seat.

A state legislature may authorise the governor to make a temporary appointment until voters fill the vacancy through an election, reflecting continued state discretion over timing and procedures.

Why Reform Happened: Problems with Legislative Selection

The movement toward the 17th Amendment grew from criticisms that the old system produced outcomes seen as undemocratic and unstable.

Key criticisms of pre-1913 selection

Corruption risk: wealthy interests could attempt to influence state legislators to secure a Senate seat for a preferred candidate.

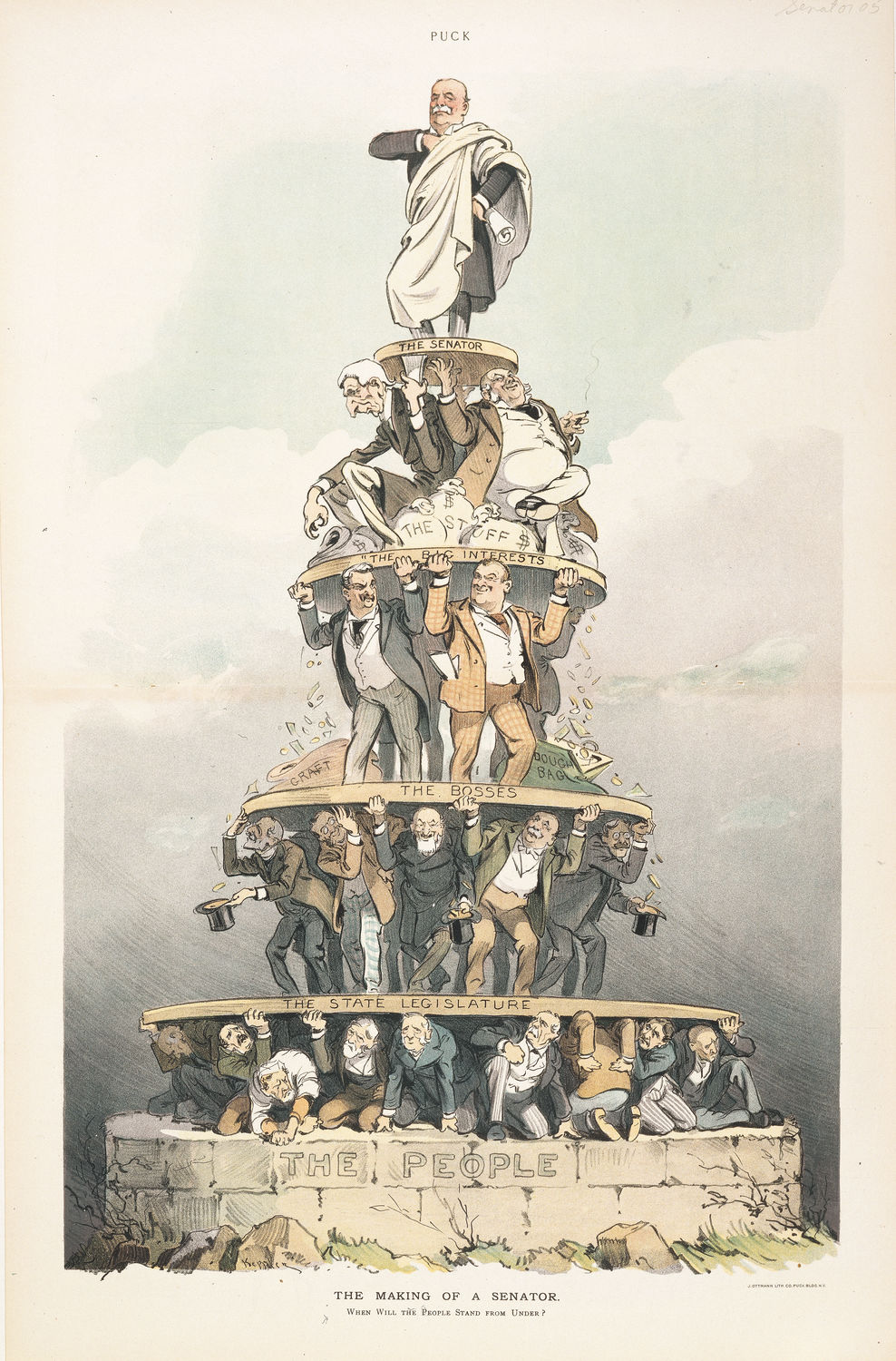

This 1905 cartoon, “The Making of a Senator,” portrays how indirect selection could place multiple intermediaries between voters and U.S. senators. By showing political bosses and corporate interests above the public, it illustrates why reformers argued that legislative selection heightened corruption risk and weakened democratic accountability. Source

Legislative deadlock: state legislatures sometimes failed to agree on a candidate, leaving seats vacant and reducing state representation in Congress.

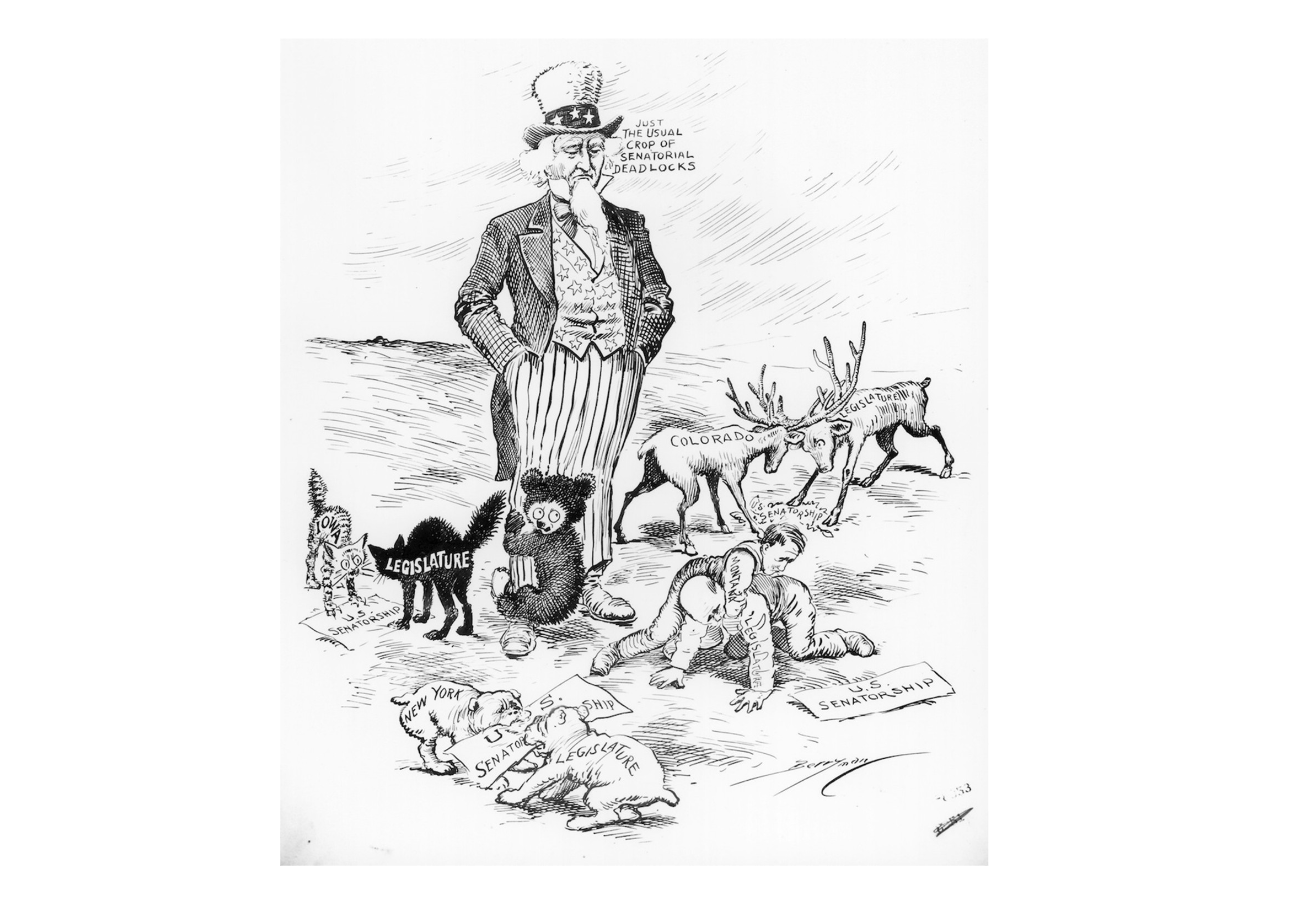

This 1911 cartoon depicts the problem of state legislative deadlocks preventing the selection of senators, a recurring issue under the pre-1913 system. It visually emphasizes how vacancies could persist when parties in a legislature could not agree, strengthening reformers’ arguments for direct election. Source

Reduced accountability: senators could prioritise state party leaders or legislative bargaining over broad public preferences.

Mismatch with democratic norms: as other political offices became more responsive to voters, indirect Senate selection appeared increasingly outdated to reformers.

These arguments became especially prominent during the Progressive Era, when reformers emphasised transparency, popular control, and curbing the power of political machines.

How Direct Election Changed Representation and Incentives

Direct election reshaped how senators build support and how they interpret their representative role.

Increased electoral accountability

Because senators must now win statewide elections:

They are more directly responsive to voters’ preferences and shifting public opinion.

They must develop broader public coalitions rather than relying on a majority inside a state legislature.

Public-facing activities—such as constituent outreach, policy messaging, and statewide visibility—become more central to political survival.

Campaigning and coalition-building

Direct election encourages:

Statewide campaign organisations and broader fundraising efforts.

Greater reliance on mass communication and public image.

Stronger incentives to take positions that appeal to statewide electorates, including independents and cross-pressured voters.

Effects on Federalism and the Senate’s Role

The 17th Amendment is often discussed as a turning point in federalism because it altered state influence over the Senate.

Shifting the state–national relationship

Under legislative selection, state governments had a formal mechanism to shape national policymaking through their chosen senators.

Under direct election, senators remain representatives of their states, but their electoral connection is to the people, not state institutions.

This can reduce the Senate’s function as a direct instrument of state legislative preferences, even while senators still advocate for state interests.

Continuity alongside change

Even with direct election, states retain important roles by:

Administering Senate elections under state election law (within constitutional limits).

Setting procedures for filling vacancies (especially temporary appointments and election timing).

FAQ

Some states adopted informal systems that mimicked direct election.

“Oregon System” style plans let voters indicate their Senate preference, and legislative candidates pledged to respect the result.

This created political pressure on legislatures to follow the popular choice even without a federal constitutional requirement.

No. Vacancy rules vary by state law.

Some states require a special election with no interim appointment.

Others permit a temporary gubernatorial appointment until an election occurs.

Timing can differ depending on how close the vacancy is to the next scheduled election.

It reduced one pathway—bargaining within legislatures—but did not remove incentives for influence.

Corruption risks can shift towards campaign finance, donor access, and political action aimed at shaping voter opinion rather than persuading legislators directly.

The original design reflected concerns about excessive democracy and a desire to protect state power.

The Senate was intended to be more insulated and to represent states as political units, balancing the directly elected House.

Not under current constitutional law.

Because the Seventeenth Amendment mandates popular election, changing back would require another constitutional amendment, not a state statute or state constitutional provision.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Identify two problems associated with the pre-1913 method of selecting U.S. senators that the Seventeenth Amendment was intended to address.

1 mark: Identifies one valid problem (e.g., corruption/bribery, legislative deadlock/vacancies, low accountability to voters).

1 mark: Identifies a second valid problem.

(6 marks) Explain how the Seventeenth Amendment changed (a) the incentives of U.S. senators and (b) the relationship between state governments and the national government.

1–3 marks (incentives): Explains that senators must win statewide popular elections, increasing responsiveness to voters, encouraging statewide campaigning/coalition-building, and changing reliance from legislators to the electorate.

1–3 marks (state–national relationship): Explains that state legislatures lost formal selection power, weakening direct institutional state control over the Senate, while noting states still administer elections and may shape vacancy-filling procedures.