AP Syllabus focus:

‘The 19th Amendment enfranchised women; the 24th eliminated poll taxes; the 26th lowered the voting age to 18.’

These three amendments illustrate how the Constitution has been amended to broaden democratic inclusion while also revealing how legal change can be uneven, contested, and shaped by federalism and enforcement.

The theme: inclusion and barriers

Voting-rights amendments typically do two things at once:

Expand the electorate by prohibiting specific forms of exclusion

Create new conflicts over enforcement because states administer elections and can adapt rules in ways that still discourage participation

A key AP Government takeaway is that constitutional change can remove one barrier while leaving room for others (administrative, social, or political) to persist.

The 19th Amendment: women’s suffrage

Core change

The 19th Amendment (1920) prohibits denying the right to vote on account of sex, meaning states cannot legally exclude voters simply for being women.

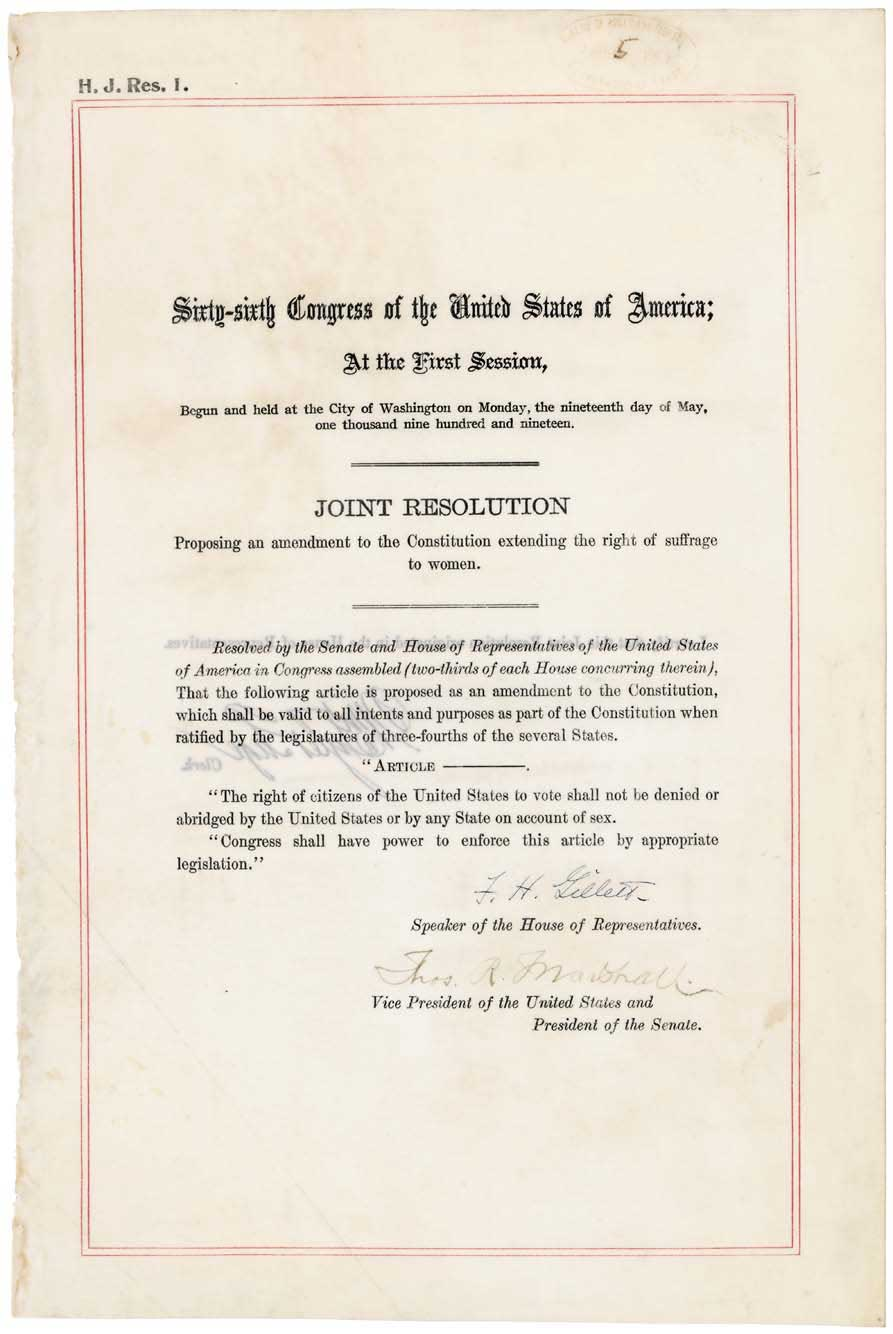

House Joint Resolution 1 proposing the 19th Amendment, shown as an original National Archives document. Using a primary-source image helps connect the abstract idea of “constitutional change” to the real legal text Congress sent to the states for ratification. Source

It transformed women from a largely excluded group into a constitutionally protected voting constituency.

Inclusion effects

Expanded political participation by adding millions of potential voters to the electorate

Increased incentives for parties and candidates to address issues important to women as an organised voting bloc

Reinforced the idea that voting access can be expanded through constitutional amendment, not only through ordinary legislation

Barriers that could remain

Even with formal constitutional protection, participation can still be limited by factors such as:

Registration requirements and complex election administration

Social intimidation or unequal access to information and transportation

Discriminatory practices that affect particular groups of women differently (especially where barriers overlap with race, language, or class)

The 24th Amendment: eliminating poll taxes

Core change

The 24th Amendment (1964) bans poll taxes in federal elections, removing a direct financial hurdle that historically reduced turnout among poorer citizens.

Photograph of President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the newly ratified 24th Amendment banning poll taxes (February 4, 1964). The photo provides historical context for how a constitutional rule change became part of federal law and public governance practice. Source

Poll tax: A required fee a person must pay to be eligible to vote, functioning as a financial barrier to participation.

This change reflects a shift toward viewing voting as a fundamental democratic right that should not depend on ability to pay.

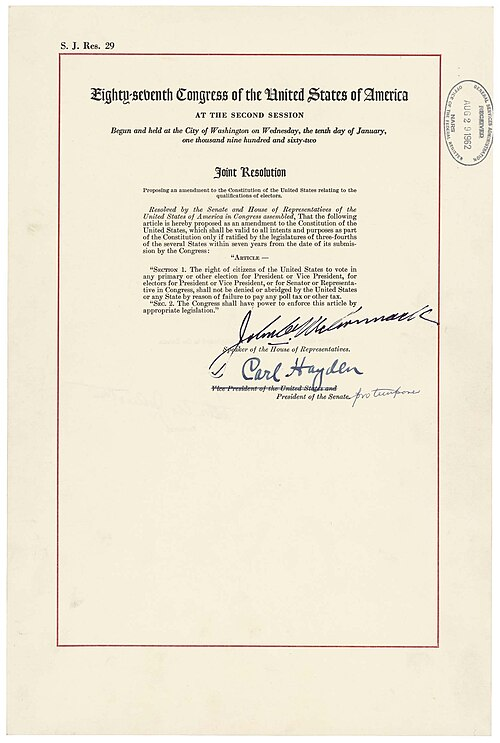

Primary-source scan of the Joint Resolution proposing the Twenty-fourth Amendment. Reading the amendment’s structure and formal wording reinforces the idea that “inclusion” is often achieved through precise constitutional text—yet the notes’ later sections explain how practical barriers can still persist. Source

Inclusion effects

Reduced a clear, predictable obstacle that discouraged turnout

Supported broader participation by limiting state practices that could price citizens out of voting

Signalled that economic barriers can be treated as unconstitutional restrictions on political participation

Barriers and enforcement issues

The amendment’s text addressed federal elections, creating disputes about how quickly and fully similar practices would disappear at the state level

States and localities could still influence participation through other methods (for example, burdensome administrative steps), illustrating that removing one barrier does not end attempts to shape the electorate

The 26th Amendment: lowering the voting age to 18

Core change

The 26th Amendment (1971) prohibits denying the right to vote to citizens 18 years or older on account of age. It constitutionalised youth suffrage nationally and prevented states from maintaining a higher voting age.

Inclusion effects

Immediately expanded the electorate to include millions of younger citizens

Strengthened the democratic principle that those subject to major public decisions should have a voice in selecting leaders

Increased the political importance of issues salient to younger voters (education costs, employment, and public policy affecting young adults)

Barriers that could remain

Lowering the voting age does not guarantee high youth turnout. Obstacles can include:

Frequent moves and unstable housing (making registration harder)

Lower levels of habitual voting and weaker ties to parties or local politics

Administrative burdens that may disproportionately affect first-time voters

Why these amendments matter for AP Government

Constitutional expansion versus practical participation

These amendments show a consistent pattern:

Legal inclusion can be achieved through constitutional rules

Practical access still depends on how elections are administered and how aggressively rights are protected

Federalism and the continuing struggle over rules

Because states run elections, conflicts often shift from “Who is eligible?” to “How easy is it to participate?” Even after constitutional expansion, debates continue over which rules promote election integrity versus which create unnecessary barriers to turnout.

FAQ

It was designed to target a specific, widely criticised barrier while navigating political resistance and constitutional debates about state control of elections.

This limited scope meant later legal and political fights were still needed to fully eliminate the practice everywhere.

They used sustained coalition-building and messaging that linked voting rights to democratic legitimacy.

Common strategies included:

State-by-state campaigning

National lobbying of parties and officeholders

Public demonstrations and persuasion campaigns

No. It prohibits age-based denial for citizens 18+, but it does not mandate particular youth-friendly procedures.

States still shape access through rules on registration, identification, and polling administration (so long as they do not violate constitutional protections).

Formal eligibility does not remove practical obstacles.

Unequal turnout can persist due to:

Administrative burdens

Information gaps

Differential resources (time, transport, childcare)

Social pressures that discourage participation

It authorises Congress to pass laws supporting the amendment’s guarantee.

In practice, enforcement power can involve:

Setting standards or penalties for violations

Authorising federal oversight mechanisms

Creating legal tools that help courts apply the constitutional rule

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Describe one way the 24th Amendment expanded political participation in the United States.

1 mark: Identifies that it banned/eliminated poll taxes in federal elections.

1 mark: Describes how this removed a financial barrier and could increase turnout/participation, especially among poorer voters.

(6 marks) Analyse how the 19th, 24th, and 26th Amendments demonstrate both expanded inclusion and the persistence of barriers to voting.

1 mark: Accurate description of the 19th Amendment (sex cannot be used to deny the vote).

1 mark: Accurate description of the 24th Amendment (poll taxes barred in federal elections).

1 mark: Accurate description of the 26th Amendment (vote extended/protected for citizens aged 18+).

1 mark: Explains inclusion (each amendment enlarges/protects the electorate).

1 mark: Explains persistence of barriers (states can use administrative or practical hurdles even when formal eligibility expands).

1 mark: Uses amendment-linked reasoning to connect constitutional rules to real-world participation (e.g., enforcement/federalism limits or non-financial obstacles).