AP Syllabus focus:

‘Rational choice voting is based on perceived self-interest; retrospective voting judges whether incumbents should be reelected based on recent performance.’

Voting behaviour models help explain how citizens make choices in elections. Two commonly tested approaches are rational choice voting, centred on self-interest, and retrospective voting, which evaluates incumbents by looking back at recent outcomes and performance.

Core idea: models simplify voter decision-making

Voting decisions are complex, so political scientists use models of voting behaviour to highlight a dominant logic behind choices.

A model is not a perfect description of every voter

Different voters may use different logics in different elections

Models can be combined: a voter may weigh self-interest and still “grade” incumbents on results

Rational choice voting model

Rational choice voting assumes individuals act strategically to maximise benefits and minimise costs, given the information they have.

Rational choice voting — a voting decision based on a voter’s perceived self-interest, choosing the option expected to produce the greatest personal benefit.

In this model, voters treat politics like a choice among alternatives and ask, “Which candidate or party helps me most?”

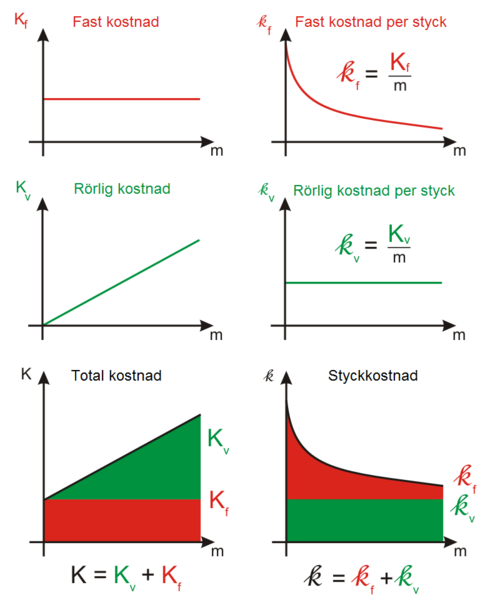

A cost–benefit diagram illustrating how people compare alternatives by weighing costs against benefits to identify a “best” choice. In rational choice voting, students can think of candidates/policies as competing options whose perceived net benefits differ across voters. The key takeaway is not precise math but the logic of trade-offs and maximization under constraints. Source

How rational choice works in practice

Key steps voters may take (explicitly or intuitively) include:

Identify personal priorities (income, taxes, job security, education costs, healthcare access)

Estimate which candidate’s policies will best serve those priorities

Consider trade-offs (a benefit in one area may come with a cost in another)

Choose the option with the highest expected net benefit

Information limits and shortcuts

Rational choice does not require perfect information; it assumes voters use perceptions of self-interest. Because gathering political information has costs (time, attention, expertise), rational choice often relies on shortcuts such as:

Candidate reputations for competence

Simple issue positions (“raises taxes” vs “cuts services”)

Endorsements from trusted groups

Broad labels that signal likely policy direction

What rational choice predicts

Voters should be responsive to policy stakes that affect their lives

Shifts in personal circumstances can change vote choice

Competing messages matter because they change perceived costs and benefits

Retrospective voting model

Retrospective voting focuses less on promises and more on results, treating elections as a performance review of those currently in power.

Retrospective voting — voting based on judging whether incumbents deserve re-election according to their recent performance and outcomes.

A central concept here is the incumbent, meaning the current officeholder (or, more broadly, the party currently governing). Retrospective voters ask: “Are things going well enough to keep them in office?”

Reward–punish logic

Retrospective voting often works as a simple accountability mechanism:

If conditions seem improved or well-managed, voters reward incumbents with re-election

If conditions seem worse or poorly managed, voters punish incumbents by voting them out

What “performance” can mean

Retrospective evaluations may include:

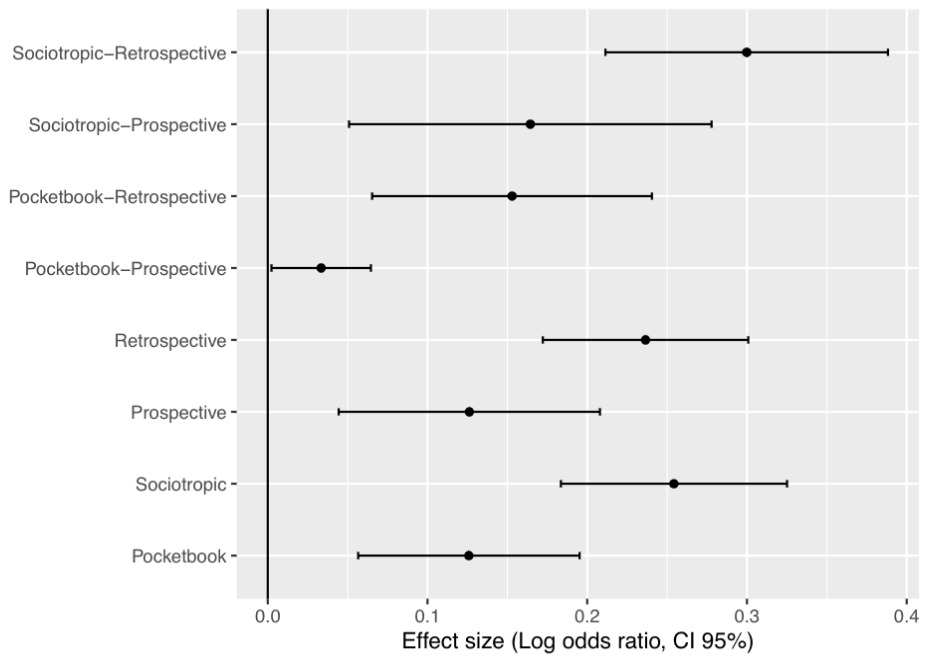

A meta-analysis plot comparing estimated effect sizes across common economic-voting measures (e.g., sociotropic vs. pocketbook; prospective vs. retrospective), with confidence intervals. It illustrates how scholars operationalize retrospective evaluations—often as judgments about recent national economic conditions—and then estimate how strongly those perceptions predict incumbent support. This situates retrospective voting as an evidence-based accountability model rather than just a descriptive idea. Source

Economic conditions (jobs, prices, growth)

Government handling of major events (crises, disasters, conflicts)

Perceived competence, honesty, or responsiveness

Policy outcomes voters notice in daily life

Because it relies on recent experience, retrospective voting can operate even when voters do not know detailed policy proposals.

Strengths and vulnerabilities of retrospective voting

Strength: strengthens democratic accountability by linking outcomes to electoral consequences

Vulnerability: voters may blame incumbents for factors outside government control or credit them for good luck, depending on perceptions

Comparing the models: what to emphasise

Both models describe plausible voter reasoning, but they highlight different questions:

Rational choice: “Which option best advances my interests going forward (as I understand them)?”

Retrospective: “Have the people in power performed well enough to deserve another term?”

In AP terms, focus on how each model explains:

Why a voter might support a candidate despite weak party loyalty (self-interest)

Why incumbents may lose even with strong campaigning (negative evaluations of recent performance)

Why messaging and perceptions matter (both models depend on what voters think is true)

FAQ

They often use indicators such as income level, occupation, reliance on public benefits, or exposure to specific policies.

Researchers may compare:

voters’ material circumstances

their stated policy preferences

their reported vote choice

It can be either, depending on what voters notice and prioritise.

Some voters focus on personal finances, while others judge broader conditions like national economic confidence or government competence.

Yes. Voters may evaluate the incumbent president, the governing party, or the party controlling key institutions.

Attribution varies with visibility: highly visible leaders are more likely to be credited or blamed.

If voters perceive that their self-interest aligns strongly with one side’s policy bundle, cost–benefit reasoning can reinforce consistent support.

Polarisation can also rise when voters see the opposing side as imposing high costs.

Uncertainty affects expectations about benefits (rational choice) and responsibility for outcomes (retrospective).

When uncertainty is high, voters may rely more on simple cues (competence signals, broad impressions) rather than detailed policy knowledge.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Define retrospective voting and explain one way it can affect whether an incumbent is re-elected.

1 mark: Accurate definition: voting based on judging incumbents’ recent performance/outcomes.

1 mark: Explains an effect: voters reward good performance with re-election or punish poor performance by voting the incumbent out.

(6 marks) Compare rational choice voting and retrospective voting as models of voter behaviour. In your answer, explain one strength and one limitation of each model.

2 marks: Comparison

1 mark: Rational choice = perceived self-interest/cost–benefit logic.

1 mark: Retrospective = judging incumbents by recent performance/outcomes.

2 marks: Strengths (1 each)

1 mark: Rational choice strength explained (e.g., links policy stakes to vote choice).

1 mark: Retrospective strength explained (e.g., promotes accountability via reward–punish).

2 marks: Limitations (1 each)

1 mark: Rational choice limitation explained (e.g., limited information leads to imperfect cost–benefit judgements).

1 mark: Retrospective limitation explained (e.g., voters may misattribute outcomes beyond incumbents’ control).