AP Syllabus focus:

‘Communities in the arid Great Basin and the western Great Plains adapted by developing largely mobile lifestyles suited to their environments.’

Indigenous societies in the Great Basin and Great Plains developed highly adaptive, mobile ways of life shaped by arid climates, scarce resources, and shifting ecological conditions before European contact.

Environmental Foundations of Mobility

The Great Basin: Aridity and Resource Scarcity

The Great Basin, stretching across present-day Nevada, Utah, and parts of Idaho and Oregon, was defined by its arid climate, limited rainfall, and unpredictable food availability.

Map of the Great Basin culture area, showing the desert basin between the Sierra Nevada and the Rocky Mountains and locating groups such as the Shoshone, Paiute, Ute, and Washoe. The shaded region illustrates the arid landscapes that encouraged mobile hunting-and-gathering lifeways. Modern political boundaries appear as extra detail not required by the AP syllabus but help orient the region geographically. Source.

These environmental pressures encouraged Indigenous groups such as the Shoshone, Paiute, and Ute to adopt highly flexible subsistence strategies built around mobility.

Seasonal temperature extremes and scarce water sources shaped migration cycles.

Communities prioritized portable material culture to support constant movement.

Hunting and gathering remained central because agriculture was impractical in most areas.

Nomadic lifestyle: A pattern of movement in which communities regularly relocate to access food, water, or other essential resources rather than settling permanently.

Mobility also helped prevent depletion of sensitive ecosystems, reinforcing cultural practices of environmental stewardship.

The Great Plains: Grasslands and Bison Ecology

The Great Plains, extending from Texas to Canada, provided a contrasting environment of broad grasslands, limited woodlands, and large herds of American bison.

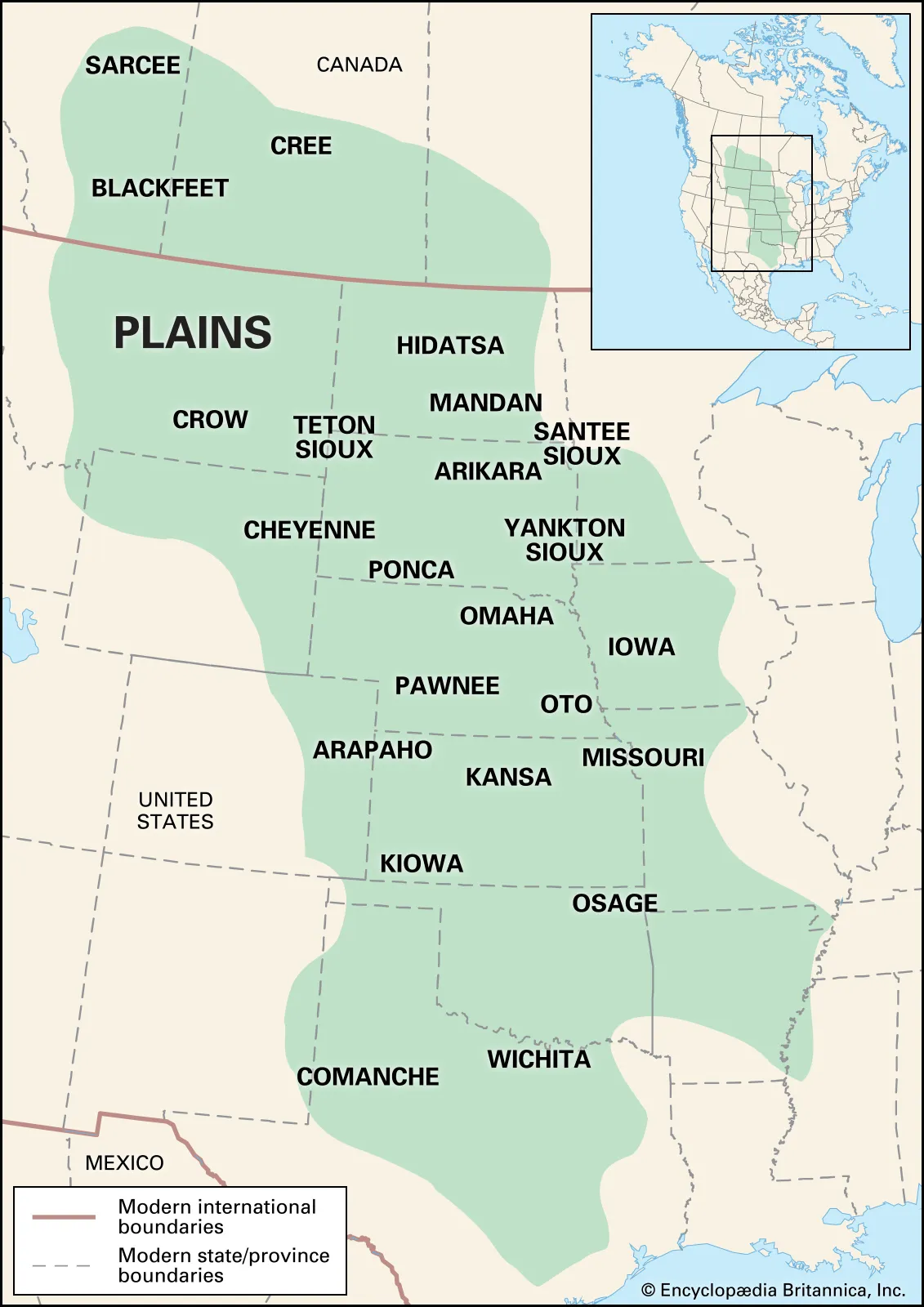

Map of the Plains culture area, showing the vast grassland region from southern Canada to Texas and locating groups including the Crow, Cheyenne, Pawnee, and Kiowa. The highlighted region helps illustrate the ecological conditions that shaped mobile, bison-focused subsistence. Modern borders and an inset locator appear as extra contextual details beyond the AP syllabus. Source.

Before the arrival of the horse, Plains groups such as the Apache, Arapaho, and Lakota were semi-nomadic, following bison herds seasonally while establishing temporary camps.

Bison migrations shaped the timing and direction of travel.

Wood scarcity influenced the development of lightweight shelters, such as early forms of tipis.

These societies demonstrated how ecological knowledge underpinned Indigenous adaptations to diverse landscapes.

Social and Cultural Dimensions of Mobility

Family Structure and Regional Networks

Mobile communities relied on flexible kinship networks that allowed families to disperse or regroup based on seasonal needs. Family units often operated as autonomous bands during migrations but gathered with larger groups for ceremonies or resource-rich seasons.

Decision-making power often rested with small family clusters.

Leadership emphasized consensus and adaptability rather than centralized authority.

Mobility thus reinforced decentralized political structures, enabling rapid movement without disrupting cultural cohesion.

Material Culture and Technological Adaptation

Because constant movement required lightweight, portable tools, both Great Basin and Plains societies developed technologies that maximized efficiency and flexibility.

Basketry thrived in the Great Basin, where baskets served as containers, cooking vessels, and gathering tools.

Spears, atlatls, and later bows and arrows supported hunting across wide territories.

Clothing was designed for durability, temperature variation, and quick travel.

These innovations reveal how cultural development was deeply intertwined with environmental challenges.

Subsistence Patterns Shaped by Mobility

Great Basin Foraging and Seasonal Rounds

Great Basin groups traveled in seasonal cycles to harvest foods that appeared briefly and irregularly.

Key resources included:

Seeds and nuts such as pinyon pine nuts

Small game including rabbits and rodents

Fish from scarce lakes and streams

Wild plant tubers and berries

This pattern of small, dispersed groups moving frequently minimized resource depletion and maximized survival in a harsh landscape.

Great Plains Hunting and Bison Dependence

Bison provided Plains societies with food, clothing, tools, and materials for shelters. Their mobility allowed them to follow herds across long distances.

Bison meat was preserved through drying or pounding to make pemmican, a high-calorie food source.

Skins became clothing, bedding, and coverings for dwellings.

Bones became tools and weapons.

Before horses, hunting required stealth, communal coordination, and intimate knowledge of animal behavior. Mobility allowed communities to remain in proximity to bison herds.

Mobility as an Adaptive Strategy

Environmental Pressures and Flexible Lifestyles

Both regions illustrate how mobility served as a core adaptive strategy, enabling Indigenous peoples to thrive within ecosystems that could not sustain large permanent settlements.

Movement prevented overuse of fragile resources.

Seasonal knowledge ensured communities arrived at the right place and time for specific foods.

Social structures supported rapid relocation without disrupting cultural cohesion.

Diversity Within Mobile Societies

While mobility united these societies, significant variation existed across regions.

Great Basin groups were typically more dispersed and traveled in smaller bands.

Plains groups, even before horses, periodically gathered in larger numbers due to the support of bison-rich environments.

Some Plains communities practiced limited agriculture, blending mobility with semi-sedentary practices.

Mobility therefore represented a spectrum, shaped by the distinct ecological realities of each region.

Mobility and Long-Term Cultural Development

Continuity and Change Before European Contact

By 1491, centuries of adaptation had produced diverse, complex societies whose mobility reflected deep environmental knowledge. Their lifeways were neither primitive nor static; rather, they were dynamic systems optimized for survival in challenging landscapes.

Interregional trade routes connected Basin and Plains cultures.

Seasonal gatherings facilitated cultural exchange, marriage alliances, and spiritual practices.

Mobility fostered resilience, enabling communities to endure climatic shifts, resource fluctuations, and ecological stressors.

These patterns defined Indigenous life in the Great Basin and Great Plains and shaped their responses when Europeans eventually entered the region.

FAQ

Mobility helped Indigenous groups maintain wide-ranging trade relationships by allowing bands to travel long distances to exchange goods such as obsidian, shells, hides, pigments, and plant fibres.

Regular movement also meant that trade routes were flexible rather than fixed, shifting according to seasonal gatherings, environmental conditions, and intertribal diplomacy.

In the Plains, larger seasonal congregations around resource-rich areas facilitated exchanges of tools, clothing, and ceremonial items, strengthening cultural ties across vast regions.

Yes. Both regions used controlled burning to encourage the growth of plants useful for food or game and to maintain open landscapes.

In the Great Basin, burning increased seed-producing plants, which supported foraging cycles.

In the Great Plains, fire helped manage grasslands and attract grazing animals, including bison, creating predictable hunting environments that complemented mobile lifeways.

Gender roles were shaped by practical needs associated with frequent movement.

Men typically carried out long-distance hunting and scouting.

Women often managed gathering, food processing, and the construction and packing of temporary shelters.

Because households moved often, women’s expertise in organising portable domestic life was crucial, and some tasks were shared flexibly depending on season and necessity.

Mobility meant that many ceremonies were tied to seasonal events, resource cycles, or specific landscapes.

In the Great Basin, spiritual practices often centred on springs, lakes, or mountains visited during annual rounds.

In the Plains, communal gatherings for hunts or summer meetings facilitated large-scale ceremonies that reinforced social bonds and transmitted cultural knowledge across bands.

Drought reduced the availability of both plant and animal resources, forcing groups to expand their range or alter seasonal patterns.

In the Great Basin, families sometimes split into smaller units to reduce pressure on resources.

In the Plains, reduced bison numbers could push groups into marginal areas or require increased reliance on small game and gathered foods, intensifying competition with neighbouring tribes.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the environmental conditions of the Great Basin shaped the mobility of Indigenous societies before European contact.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a relevant environmental condition (e.g., aridity, scarce water sources, unpredictable food availability).

1 mark for describing how this condition limited permanent settlement or agriculture.

1 mark for explaining how this led to mobile hunting-and-gathering patterns or frequent seasonal movement.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how the subsistence practices of Great Plains societies contributed to the development of mobile lifestyles before the arrival of the horse.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a key subsistence practice (e.g., bison hunting).

1 mark for explaining why this practice required mobility (e.g., following migratory herds).

1 mark for describing a technological or material adaptation that supported mobility (e.g., lightweight shelters such as tipis).

1 mark for discussing the role of seasonal movement or temporary camps.

1–2 marks for a developed explanation linking subsistence practices to wider social or environmental patterns (e.g., kinship flexibility, resource management, or ecological knowledge).