AP Syllabus focus:

‘The spread of maize cultivation from Mexico into the American Southwest supported settlement, economic development, advanced irrigation, and greater social diversification.’

Before European contact, maize agriculture and irrigation in the Southwest enabled population growth, permanent settlements, and cultural complexity through environmental adaptation and innovative water-management practices.

Maize Cultivation in the American Southwest

The introduction and spread of maize agriculture transformed the societies of the American Southwest long before Europeans arrived. Originating in central Mexico, maize became a reliable, high-yield crop that reshaped daily life, settlement patterns, and social organization among Indigenous peoples such as the Hohokam, Ancestral Puebloans, and Mogollon.

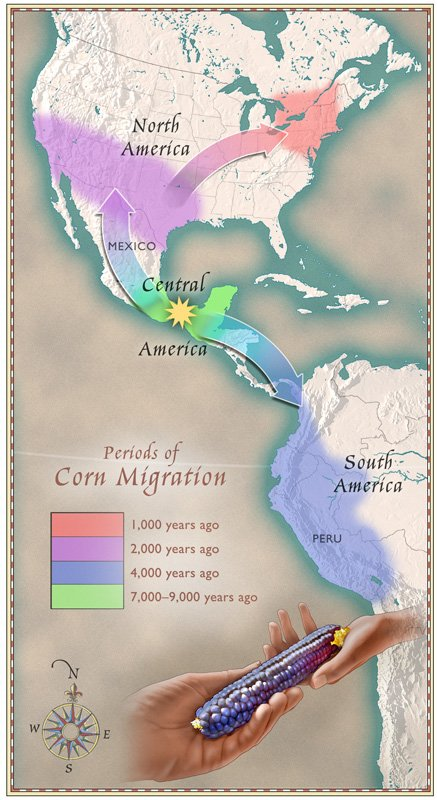

This map illustrates the spread of maize from its Mesoamerican origin into the American Southwest and other parts of North America. The directional arrows show how maize cultivation knowledge moved over centuries. The map also includes maize’s expansion into Central and South America, which exceeds AP requirements but provides broader context. Source.

Its gradual diffusion northward required generations of experimentation, as farmers adapted planting techniques to the region’s arid climate, thin soils, and unpredictable rainfall. By 1200 CE, maize had become central to subsistence strategies, providing the caloric stability necessary for long-term community growth.

Maize: A domesticated grain originating in Mesoamerica, valued for its high productivity and adaptability, making it a foundational crop for many Indigenous societies.

As maize developed into a dietary and cultural cornerstone, Southwestern communities shifted away from purely nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyles. Instead, they invested in permanent or semi-permanent settlements supported by storage facilities, seasonal planning, and increasingly specialized agricultural labor. These changes helped stimulate social diversification, as roles related to crop management, food preservation, architectural construction, and ritual activities became more defined.

Advanced Irrigation and Water-Management Systems

Environmental Challenges in an Arid Landscape

The American Southwest is characterized by sparse rainfall, extreme temperature variation, and limited surface water sources. To make agriculture sustainable, Indigenous farmers engineered innovative irrigation networks that redirected and conserved water in ways unmatched elsewhere in North America at the time. These adaptations demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of hydrology and landscape modification.

Irrigation: A system or method for supplying water to land or crops through channels, ditches, canals, or other artificial means.

These technologies did more than deliver water—they enabled communal planning and collective labor, reinforcing the development of structured societies. The need to maintain canals, distribute water equitably, and schedule planting seasons fostered political cooperation and strengthened community governance.

Major Irrigation Cultures

Hohokam engineers constructed extensive canal systems along the Salt and Gila Rivers in modern-day Arizona.

This photo shows a preserved prehistoric Hohokam canal segment at Park of the Canals in Mesa, Arizona. The defined earthen channel demonstrates how Hohokam irrigation diverted water from nearby rivers onto maize fields. The image focuses on canal engineering without adding information beyond the irrigation emphasis in the syllabus. Source.

These canals stretched for miles, some reaching impressive widths and depths that required coordinated labor forces. Their networks supported crops such as maize, beans, and squash, while allowing communities to thrive in otherwise inhospitable environments.

The Ancestral Puebloans used a different approach, relying largely on check dams, terracing, and water-catchment basins.

This image shows a terraced hillside engineered to slow runoff and retain moisture, enabling crops to grow in arid environments. The stone walls create stable, flat agricultural surfaces, reflecting the strategies used by Ancestral Puebloan farmers. The ORIAS description includes additional context on warmth retention, slightly beyond AP scope but still relevant to water-conserving agriculture. Source.

These structures slowed runoff, preserved moisture, and reduced soil erosion in high desert regions. Puebloan irrigation was often paired with dry farming techniques, which took advantage of natural depressions and floodplains to retain water around planted fields.

Core Components of Southwestern Irrigation

Southwestern irrigation systems varied regionally but generally included:

Canals transporting river or floodwater to fields

Ditches and laterals distributing water across agricultural plots

Reservoirs capturing seasonal runoff for later use

Check dams and terraces slowing water flow and stabilizing soil

Communal maintenance practices ensuring long-term viability

These components enabled consistent crop yields even during periods of low rainfall, making maize agriculture a dependable foundation for community life.

Settlement Patterns and Population Growth

Permanent Villages and Architecture

The dependable productivity of maize supported the formation of permanent villages and increasingly complex architectural structures. The Ancestral Puebloans built multi-story dwellings, kivas, and room blocks from stone and adobe. Their large communities, such as Chaco Canyon, relied on extensive planning and resource coordination—possible only with agricultural surplus.

In Hohokam areas, settlements expanded around major canal systems. Villages were often spaced methodically to ensure equitable access to water. Social structures emerged around canal management, ritual obligations, and trade networks that connected communities across the broader region.

Demographic and Social Diversification

Reliable maize harvests contributed to population growth, which in turn encouraged occupational specialization. Societies began to exhibit greater social diversification, including divisions of labor tied to agriculture, construction, pottery, trade, and ceremonial leadership. Surplus food freed some individuals to engage in craft production or religious activity, enhancing cultural complexity.

Economic Development and Regional Exchange

Agricultural Surplus and Trade

Maize production and irrigation allowed Southwestern societies to generate agricultural surplus, which facilitated trade both within the region and with distant peoples. Exchange networks carried items such as:

Pottery and textiles

Turquoise and shell ornaments

Obsidian, stone tools, and maize products

Ritual objects and cultural goods

These networks connected the Southwest to Mesoamerica and the Great Plains, enabling cultural and technological exchange. Trade also reinforced political alliances and helped stabilize economies during periods of environmental stress.

Agricultural Innovations and Long-Term Impact

Over time, farmers selected maize varieties suited to local climates, improving drought resistance and yield. Rotational planting, soil-management strategies, and the combination of maize with beans and squash (the “Three Sisters”) enriched soils and diversified diets. These practices highlight an advanced ecological knowledge that contributed to long-term sustainability.

Social and Cultural Dimensions of Maize Agriculture

Ritual Significance

In many Southwestern cultures, maize held profound religious meaning. Ceremonies marking planting, rainfall, and harvest reaffirmed community bonds and expressed gratitude to spiritual forces believed to sustain life. Agricultural success was closely tied to cosmological beliefs, reinforcing maize’s importance beyond mere subsistence.

Political Organization

The need to organize irrigation labor and allocate water rights contributed to the development of leadership structures. Community councils or ritual specialists often oversaw water distribution, coordinated maintenance, and mediated disputes. These responsibilities demonstrated how environmental adaptation encouraged more complex political systems.

Transformative Effects on Indigenous Societies

The spread of maize cultivation into the American Southwest reshaped communities by enabling stable food supplies, population growth, and enduring settlements. Advanced irrigation systems showcased remarkable engineering skill and collective organization. Together, these developments supported economic growth, long-term social diversification, and cultural complexity among Indigenous societies well before European arrival.

FAQ

Maize spread gradually through a combination of trade, migration, and cultural exchange among interconnected Indigenous communities. Its movement northward was not a single event but a long process involving experimentation and adaptation to new climates.

Farmers refined planting techniques as maize entered cooler and drier environments, selecting varieties that matured more quickly or used water more efficiently. This incremental adaptation allowed maize to become a dependable staple in regions far from its tropical origins.

The Southwest’s extreme aridity and limited rainfall created a strong incentive for technological innovation. Communities had to manipulate scarce water resources if they wished to sustain agriculture.

The presence of major rivers such as the Salt and Gila also made large-scale canal engineering possible. In regions without these waterways, other Indigenous groups relied more heavily on dry farming or seasonal mobility.

Maize agriculture created new labour demands throughout the year, including planting, tending, harvesting, and storing crops. This encouraged more structured divisions of labour.

Women often played central roles in processing maize, while men typically undertook large-scale construction projects such as canal maintenance. These distinctions were not rigid but reflected the expanding range of tasks created by agricultural production.

Reliance on a single major crop made communities vulnerable to drought, flash flooding, and seasonal unpredictability. Poor water years could sharply reduce yields.

To limit risk, communities used strategies such as building surplus storage pits, planting fields in multiple locations, and maintaining extensive irrigation networks. These methods helped buffer communities against natural fluctuations.

Shared water sources created both opportunities for cooperation and potential for conflict. Canal maintenance required coordinated labour, which encouraged alliances between neighbouring groups.

At the same time, disputes over water access or canal routes sometimes led to tensions, particularly in periods of drought. As a result, many communities developed governance structures or ritual frameworks to manage water rights and reduce conflict.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the spread of maize cultivation supported the development of permanent settlements in the American Southwest prior to European contact.

Question 1

1 mark: Identifies a valid effect of maize cultivation (e.g., stable food supply, increased agricultural productivity).

2 marks: Shows a clear link between maize cultivation and settlement (e.g., ability to sustain larger populations in one place).

3 marks: Provides accurate detail or an example from a specific Southwestern culture (e.g., Ancestral Puebloans building permanent dwellings; Hohokam villages forming along canal systems).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how irrigation systems contributed to social and economic change in Indigenous societies of the American Southwest before 1607. In your answer, refer to specific cultural groups and agricultural practices.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks.

1–2 marks: Provides general statements about irrigation or agriculture with limited detail.

3–4 marks: Describes specific irrigation methods (e.g., canals, terraces, check dams) and links them to changes in society or the economy.

5–6 marks: Offers well-developed analysis using named groups (e.g., Hohokam, Ancestral Puebloans) and explains multiple consequences (e.g., labour organisation, population growth, increased trade, social diversification).