AP Syllabus focus:

‘In the Northeast, Mississippi River Valley, and Atlantic seaboard, some societies mixed agriculture with hunting and gathering, encouraging permanent villages.’

Eastern Native American societies blended agriculture, hunting, and gathering in ways that encouraged sustained settlement, supporting complex communities shaped by regional environments, seasonal needs, and diverse cultural practices before European contact.

Mixed Subsistence Economies in the Eastern Woodlands

Eastern North America hosted some of the most diverse and densely populated Indigenous societies in pre-contact America. The region’s vast forests, rich soils, and abundant waterways supported an economic pattern in which communities combined agriculture, hunting, and gathering to meet food needs, build social structures, and develop long-term settlements. Unlike fully agricultural societies in Mesoamerica or highly mobile groups of the Great Basin, Eastern societies embraced an adaptable, mixed subsistence economy that evolved over centuries.

The Three Sisters and Agricultural Foundations

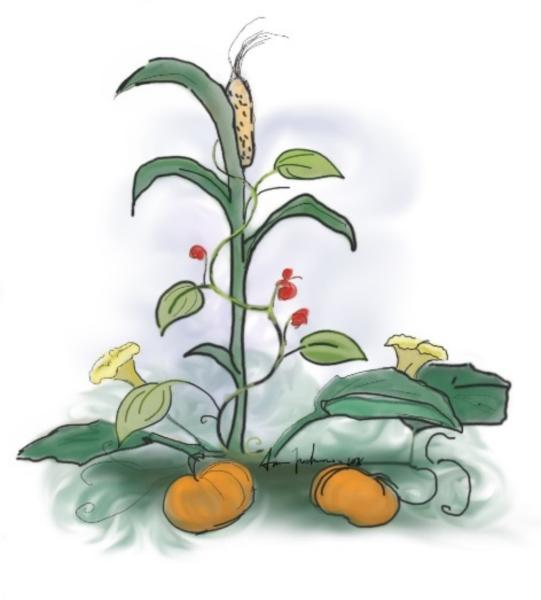

A defining feature of Eastern agriculture was the cultivation of the Three Sisters: maize, beans, and squash.

This illustration shows the Three Sisters system, with maize growing upright, beans climbing the stalk, and squash spreading along the ground. It visually explains how these crops supported one another and created a productive, resilient agricultural base for many Eastern Indigenous societies. The drawing focuses on plant relationships and does not add content beyond the level of detail needed for this subtopic. Source.

These crops were typically grown together in a single mound, using a complementary system in which maize provided a structure for beans to climb, while squash leaves shaded the soil and reduced weed growth. This agricultural triad produced reliable yields and supported population growth in several cultural regions, especially in the Mississippi River Valley and the Northeast.

Mixed Subsistence Economy: An economic system combining farming, hunting, gathering, and sometimes fishing to ensure a stable and diverse food supply.

Agriculture did not eliminate mobility entirely. Communities adjusted planting and harvesting cycles according to seasonal rhythms, yet they increasingly developed year-round or semi-permanent settlement patterns. This shift toward stability created opportunities for political centralization, ceremonial practices, and craft specialization.

Regional Variations in Eastern Mixed Economies

Although Eastern Indigenous societies shared broad subsistence strategies, each region adapted its economy to local environmental conditions and cultural traditions.

Northeast Woodlands

The Northeast Woodlands, home to groups such as the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) and various Algonquian-speaking peoples, maintained a balanced mix of agriculture and forest-based food sources. Communities planted staples in the warmer months but relied heavily on hunting deer, fishing in rivers and lakes, and gathering berries, nuts, and wild plants. Forest resources were abundant, and the ability to supplement agriculture helped reduce risks from crop failure.

Agricultural villages often featured longhouses or wigwams constructed from wood and bark.

Seasonal rounds continued, but communities returned to central villages throughout the year.

Food storage in pits and containers allowed societies to keep surpluses for winter months.

Mississippi River Valley

In the Mississippi River Valley, especially among descendants of the Mississippian culture, agriculture played a more dominant role than in the Northeast.

This reconstruction painting depicts a Mississippian town with earthen platform mounds, wooden buildings, and surrounding farmed land. It highlights how maize-based agriculture, along with other crops, sustained dense populations in permanent villages and ceremonial centers. The image also shows elite structures on mound tops and everyday activity, which provides extra context about Mississippian social hierarchy beyond the minimum required by the syllabus. Source.

Fertile floodplains encouraged the development of intensive maize agriculture, supporting larger populations and promoting permanent settlements.

Mississippian societies built platform mounds, organized labor, and developed hierarchical political structures. Even with these advances, hunting and gathering remained essential, supplementing diets with wild game, nuts, and riverine resources. The region’s mixed economy supported some of the most complex pre-contact societies north of Mexico.

Atlantic Seaboard

Along the Atlantic seaboard, communities took advantage of both agricultural fields and rich marine ecosystems. Groups such as the Powhatan and Wampanoag cultivated maize, beans, and squash but also harvested shellfish, caught fish with weirs and nets, and collected coastal plants.

Coastal abundance reduced the need for frequent relocation.

Agricultural fields were often cleared using controlled burns, a practice that improved soil fertility and hunting conditions.

Interactions between farmland and coastline created diverse food sources that supported stable villages.

Permanent Villages and Social Development

The combination of agriculture with hunting and gathering encouraged the rise of permanent villages, a hallmark of Eastern Indigenous societies before European arrival. Permanent or semi-permanent settlement enabled cultural growth, political innovation, and strengthened kinship networks.

Settlement Structure and Housing

Permanent settlements required sturdy housing, storage systems, and community planning. Longhouses, multifamily dwellings associated with the Iroquois, symbolized the extended kin networks and matrilineal social structures of the region.

This photograph shows the interior of a reconstructed Iroquoian longhouse, with central hearths, wooden support posts, and raised sleeping platforms. It illustrates how multiple related families lived together in a single elongated dwelling, reflecting the kin-based structure of many Northeastern villages. The reconstruction includes some interpretive details for museum visitors, but the layout closely matches what students need to understand about longhouses and permanent settlement. Source.

Other groups used wigwams, earthlodges, or constructed towns with central plazas and ceremonial spaces, as seen in Mississippian areas.

Social and Political Organization

Because food production was stable and diversified, communities could support specialized roles, including leaders, artisans, and religious figures. In some regions, confederacies such as the Iroquois Confederacy emerged, linking multiple nations through diplomacy and shared governance. Mixed economies provided the resources necessary for these political innovations.

Environmental Stewardship and Land Use

Eastern societies actively shaped their environments. Controlled burns, selective planting, and careful forest management increased the availability of edible plants and game. This environmental knowledge helped sustain both agricultural and wild resources, reinforcing the mixed economic system.

Cultural Significance of Mixed Economies

Economy and culture were deeply intertwined. The seasonal rhythms of planting, hunting, and gathering shaped ceremonies, gender roles, and community life. Women often oversaw agricultural production, granting them substantial authority in many Eastern societies. Men typically hunted, fished, or engaged in diplomatic and warfare activities, but both roles were vital to community identity and survival.

Mixed economies also influenced trade networks, linking Eastern societies with distant groups and facilitating the exchange of goods such as furs, copper, shells, and crafted items. These interactions enriched cultural traditions and helped maintain regional stability.

Through their adaptation to diverse environments, Eastern Indigenous societies built thriving communities that integrated agriculture with hunting and gathering. This combination created the foundation for permanent villages and supported the cultural vibrancy characteristic of the region before European contact.

FAQ

Seasonal climate shifts shaped when communities planted crops, gathered wild plants, and carried out hunting expeditions. Spring and summer were devoted to maize, bean, and squash cultivation, while autumn brought nut-gathering and intensified hunting.

Winter months emphasised food storage and crafting activities conducted within permanent or semi-permanent dwellings.

Climate variability also encouraged communities to diversify their subsistence strategies to reduce the risks of poor harvests.

Women typically oversaw agricultural production, including planting, weeding, and harvesting, and held considerable influence over stored food supplies.

Men often focused on hunting, fishing, and diplomatic or military tasks, ensuring communities had access to high-protein foods and trade relationships.

These complementary roles helped stabilise food systems and reinforced the social organisation of permanent villages.

Stable settlements allowed artisans and specialised workers to refine tools, pottery, and agricultural equipment.

Villages promoted experimentation with:

improved maize storage vessels

more efficient fishing traps and weirs

durable stone and bone tools

Permanent living arrangements also supported the transmission of these skills across generations

Permanent villages became hubs for exchanging regional resources such as furs, freshwater pearls, copper, and crafted goods.

Communities specialising in certain items traded with distant groups, creating extensive networks that linked the Northeast, Great Lakes, and Mississippi regions.

These exchanges helped spread agricultural knowledge and reinforced alliances between different societies.

Eastern Indigenous groups actively managed landscapes to increase yields from both farming and wild resources. Techniques included:

controlled burning to clear undergrowth and improve hunting conditions

selective harvesting of plants to encourage regrowth

maintaining soil fertility through crop rotation or field shifting

Such practices enhanced long-term sustainability and supported growing populations in permanent settlements.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which mixed subsistence economies contributed to the development of permanent villages among Indigenous societies in the Eastern Woodlands before European contact.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks for:

1 mark for identifying a valid feature of mixed subsistence economies (for example, combination of agriculture, hunting, gathering, or fishing).

1 mark for linking this feature to increased food stability or reliability.

1 mark for explaining how this stability supported or encouraged permanent or semi-permanent settlement.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how regional environmental differences shaped the mixed economies of Indigenous societies in the Northeast, the Mississippi River Valley, and the Atlantic seaboard before European contact. In your answer, use specific examples from at least two regions.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks using the following criteria:

1 mark for identifying that environmental diversity shaped different economic practices across regions.

1–2 marks for explaining how the Northeast relied on a balance of agriculture, hunting, and forest resources, with a clear example (such as longhouse villages or reliance on deer and fishing).

1–2 marks for explaining how the Mississippi River Valley supported more intensive agriculture due to fertile river floodplains, enabling larger, permanent settlements and mound-building societies.

1–2 marks for explaining how Atlantic seaboard societies combined agriculture with marine resources, such as fishing and shellfish collection, using an accurate example of coastal subsistence.

Answers must cover at least two regions for full marks.