AP Syllabus focus:

‘European–American Indian interactions produced both accommodation and conflict; colonists formed alliances and supplied arms as Indigenous groups sought European partners against rival Native nations.’

European–American Indian interactions in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries reflected shifting patterns of cooperation, conflict, diplomacy, and resource competition, shaping the development of North American colonial societies.

Patterns of Accommodation

European settlers and American Indian nations frequently pursued strategies of accommodation to secure trade, military assistance, and territorial stability. These arrangements varied widely across regions, revealing the diverse interests of all groups involved.

Mutual Trade Relationships

Trade formed a foundation for accommodation. European colonists depended on Native knowledge of the land and sought access to resources such as furs, food supplies, and geographic intelligence. In return, Indigenous groups looked for reliable trading partners who could supply metal tools, firearms, textiles, and manufactured goods unavailable in North America.

American Indians selectively incorporated European goods into their existing economies.

Colonists relied on Native agricultural support during early settlement periods.

Both sides recognized that trade could reduce the risk of immediate conflict.

The exchange of goods also supported cultural learning. Many Europeans adapted Native hunting techniques, while Indigenous communities integrated new materials into social and political life.

French, Dutch, and some English traders exchanged metal tools, cloth, and firearms for Native furs, reshaping Indigenous economies and tying villages into Atlantic markets.

French traders barter European goods for furs trapped by Native Americans. This scene captures how exchange of tools, textiles, and weapons underpinned diplomatic relationships and fostered limited accommodation between the groups. Although the source page includes later fur-farming context, the image itself reflects early modern trade patterns that supported Native–European alliances. Source.

Diplomacy and Negotiated Agreements

Diplomacy allowed Europeans and Indigenous groups to manage intergroup relations while protecting their interests.

Treaties were often used to formalize boundaries or secure safe passage.

Diplomatic councils relied on gift-giving, an established Indigenous practice that Europeans learned to adopt.

Interpreters and cultural brokers—often individuals of mixed ancestry—helped maintain alliances.

These diplomatic practices reduced tensions in many regions, although misunderstandings over land ownership concepts remained frequent.

Sources of Conflict

Despite periods of accommodation, competition for resources, territory, and political power frequently escalated into violence. The AP specification emphasizes how such tensions shaped ongoing interactions between colonists and American Indians.

Land Pressure and Settlement Expansion

The expansion of colonial settlement was one of the most consistent causes of conflict. European beliefs in private land ownership clashed with Indigenous understandings of land as a shared resource.

Private Land Ownership: A legal concept in which individuals or groups hold permanent, exclusive rights to land and its use.

Settlers’ demand for farmland led to encroachment onto Native hunting grounds and village sites, sparking confrontations and punitive expeditions. These conflicts increased as colonial populations grew and agricultural exports became more profitable.

Resource Competition

Both Indigenous groups and Europeans competed for access to valuable resources—especially furs, arable land, and strategic waterways.

European rivalry, particularly between the French, Dutch, and English, intensified tensions because each power sought alliances with Indigenous nations.

Native nations also competed among themselves to control trade routes and preserve political influence.

When trade shifted or alliances changed, conflicts often erupted, destabilizing entire regions.

The struggle for economic advantage frequently overlapped with political disputes, making conflict difficult to avoid.

Alliance Formation

Alliances were central to European–American Indian relations and shaped the geopolitical landscape of the period. The AP specification highlights that Indigenous groups actively sought European partners to gain advantages over rival Native nations, while colonists used alliances to bolster security.

Indigenous Goals in Alliance Building

American Indian nations pursued alliances to advance their own strategic interests.

Alliances offered access to weapons, which significantly altered the balance of power in intertribal warfare.

Tribes such as the Iroquois Confederacy leveraged relationships with Europeans to maintain a dominant regional position.

Diplomatic partnerships helped Indigenous leaders negotiate territorial agreements from a position of strength.

The Iroquois Confederacy used diplomacy to play French and English rivals against each other, bargaining for trade goods, guns, and recognition of their territorial claims.

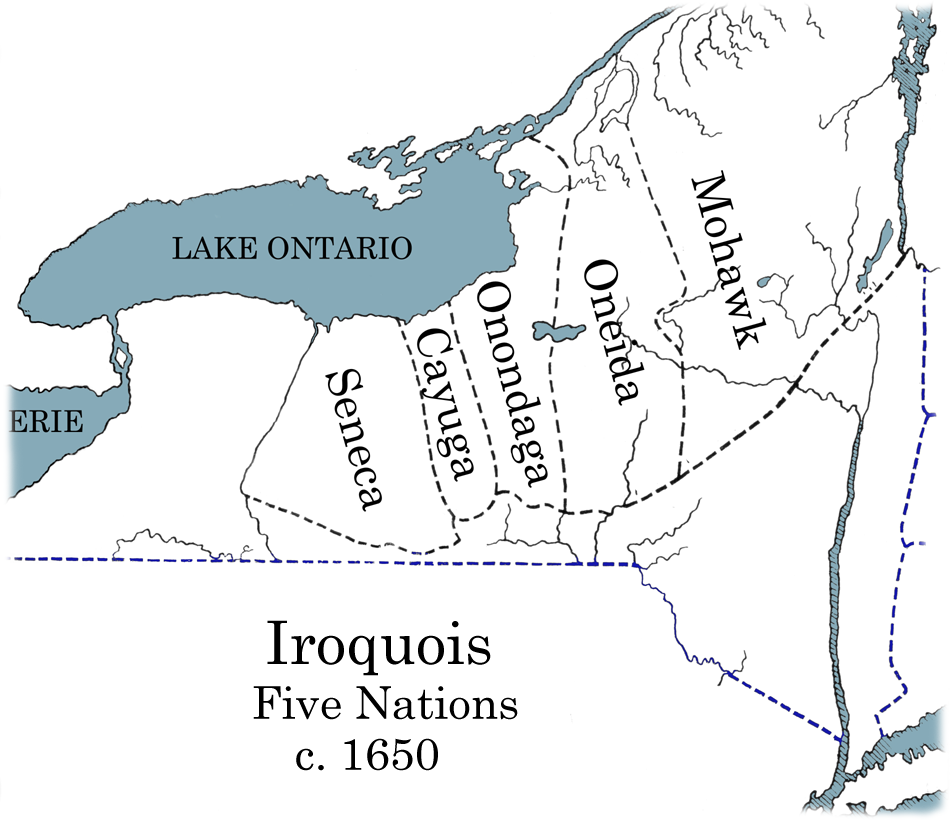

This map shows the territories of the Iroquois Five Nations around 1650. Their strategic location between French and English spheres of influence helped them leverage alliances and maintain autonomy. The map provides geographic context for the Confederacy’s role as a major diplomatic power in the colonial Northeast. Source.

Colonial Motives for Alliances

European colonists valued alliances with Native nations for reasons of defense, diplomacy, and economic advantage.

Colonists relied on Indigenous military support against rival European settlements.

Alliances enabled safer trade and exploration through unfamiliar territory.

Settlers viewed Native alliances as a means of stabilizing frontier regions.

Armed cooperation often played a role in conflicts between European empires, such as in borderland skirmishes where Indigenous fighters were essential allies.

Arms, Warfare, and Shifting Power

The AP syllabus notes that colonists supplied arms to allied Indigenous groups, a practice that had significant consequences.

The introduction of European firearms intensified intertribal conflicts.

Indigenous warriors adapted European military technologies to local warfare traditions.

Colonists used arms trading to strengthen favored alliances, deepening rivalries among Native nations.

As weapons became central to diplomacy and conflict, European powers increasingly regulated the arms trade, attempting—often unsuccessfully—to control Indigenous access to guns and ammunition.

Long-Term Impacts of Accommodation, Conflict, and Alliances

Interactions between Europeans and Indigenous groups during this period set enduring patterns in North American history.

Accommodation facilitated trade networks that tied Native communities into the Atlantic economy.

Conflict over land and resources contributed to cycles of violence that reshaped demographics.

Alliances created diplomatic precedents and military strategies that persisted into later colonial wars.

These dynamics illustrate how European–American Indian relationships were complex and reciprocal, involving negotiation, adaptation, and strategic decision-making on all sides.

In New England, the Wampanoag alliance with the Pilgrims at Plymouth involved mutual defense and trade, at least for a generation.

This illustration shows the Pilgrims concluding a peace treaty with Massasoit, leader of the Wampanoag Confederacy. The agreement established mutual defense and structured trade, demonstrating how diplomacy shaped early colonial–Indigenous relations. Although the page emphasizes epidemic disease, the image itself represents a key moment of alliance and accommodation. Source.

FAQ

European settlers believed land could be privately owned, permanently enclosed, and bought or sold as a commodity. Many American Indian nations viewed land as a shared resource whose use could be negotiated but not permanently alienated.

These contrasting worldviews meant that agreements Europeans interpreted as land sales were often understood by Indigenous leaders as temporary or conditional usage rights, creating long-term friction that fed into later conflicts and broken alliances.

Shifting alliances reflected Indigenous efforts to preserve autonomy rather than loyalty to a European empire.

Indigenous nations sometimes switched alliances to:

• Access better trade terms

• Acquire more reliable supplies of weapons

• Exploit rivalries between Europeans

• Prevent any one European power from becoming dominant in their region

Such flexibility allowed Native communities to navigate a fluid geopolitical landscape.

Intermediaries helped bridge linguistic and cultural gaps that could otherwise derail diplomacy.

They often came from multilingual Native backgrounds, mixed-heritage families, or frontier communities, making them trusted by both sides. They guided negotiations, clarified gift-giving protocols, and helped sustain alliances during periods of tension or misunderstanding.

Their presence could mean the difference between a lasting diplomatic relationship and a breakdown in communication.

American Indian warfare was often characterised by mobility, ambush tactics, and targeting of small groups rather than large-set piece battles. Europeans quickly recognised that these tactics were highly effective in frontier environments.

As a result, alliances with Indigenous fighters gave European colonists strategic advantages in navigating terrain, conducting raids, and defending settlements. In return, Native nations leveraged European weaponry to strengthen their own military objectives.

Firearms altered the balance of power among Indigenous nations, making access to weapons a major diplomatic incentive.

Because European suppliers controlled the flow of guns and ammunition, they could:

• Reward loyal allies

• Punish hostile nations

• Influence intertribal conflicts

• Shape regional power structures

This created a cycle in which Indigenous groups sought European partnerships to maintain military parity, while Europeans used arms distribution to advance strategic interests.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which trade shaped relations between European colonists and American Indian nations in the period 1607–1754.

Question 1

1 mark

• Identifies a valid way trade shaped relations, e.g., exchange of furs for European goods.

2 marks

• Provides a basic explanation of how trade influenced interactions, such as promoting accommodation or reducing initial conflict.

3 marks

• Offers a developed explanation that directly links trade to broader patterns of diplomacy or competition, e.g., how access to firearms altered Indigenous power dynamics or encouraged alliances.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which alliances between European settlers and American Indian nations were driven by mutual strategic interests in the period 1607–1754. In your answer, consider both Indigenous and European motivations

Question 2

4 marks

• Provides a clear argument addressing the extent to which alliances were based on mutual interests.

• Describes at least one European motive (e.g., defence, territorial security, access to trade routes).

• Describes at least one Indigenous motive (e.g., acquiring weapons, gaining advantage over rival Native nations).

5 marks

• Develops the argument by explaining how these interests shaped actual alliances, such as those involving the Iroquois Confederacy or Wampanoag.

• Uses historically accurate and relevant evidence to support claims.

• Shows some awareness of differences across regions or over time.

6 marks

• Presents a well-structured and well-reasoned evaluation of the degree of mutuality in these alliances, showing how both groups used diplomacy strategically.

• Integrates multiple pieces of specific evidence, e.g., arms trading, treaty-making practices, shifting alliances between French, English, and Indigenous nations.

• Demonstrates a nuanced understanding that alliances were often temporary, conditional, and shaped by changing geopolitical pressures.