AP Syllabus focus:

‘After the Pueblo Revolt, American Indian resistance pushed Spain to accommodate some Indigenous cultural practices in the Southwest while continuing efforts to colonize the region.’

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 reshaped Spanish-Indigenous relations in the Southwest, forcing Spain to reconsider colonial practices and accommodate Pueblo culture while still pursuing imperial control.

Background to the Spanish Borderlands

The Structure of Spanish Rule in the Southwest

Spain’s northern frontier—known as the Spanish Borderlands—included present-day New Mexico, Arizona, Texas, and parts of Colorado.

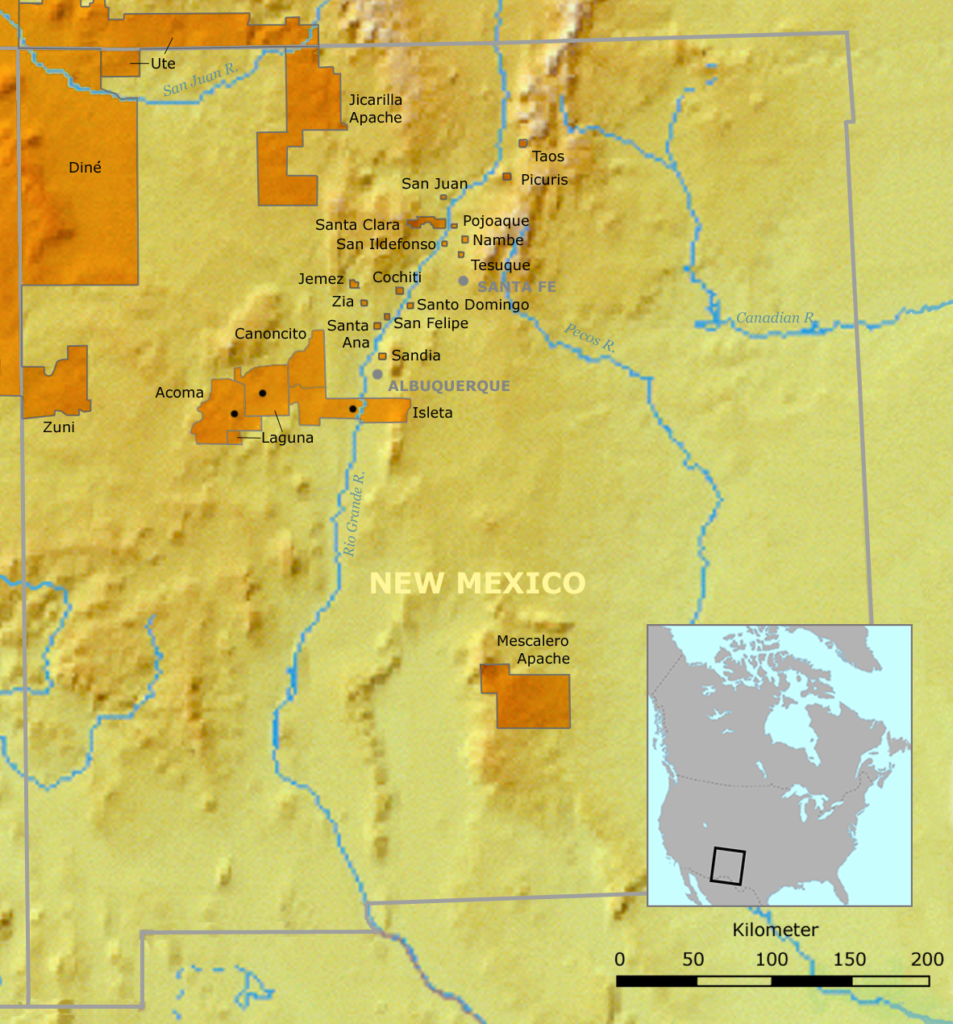

Map of Pueblo communities in present-day New Mexico, illustrating the concentration of settlements along the Rio Grande corridor. This geography shaped Spanish colonization strategies and influenced the coordinated nature of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. The map includes modern labels and more detail than required by the syllabus, but all information reinforces the historical context of the topic. Source.

These regions were characterized by dispersed settlements, a limited Spanish population, and reliance on Indigenous labor and cooperation. Spanish authority rested on three main institutions: missions, presidios, and civilian towns. Together they aimed to convert, control, and integrate Native communities into colonial society.

Spanish Demands and Pueblo Vulnerabilities

Before 1680, Spain imposed tribute, labor requirements, and religious restrictions on Pueblo peoples. Efforts to suppress Indigenous ceremonies and enforce Catholic orthodoxy created intense cultural pressure. At the same time, drought, famine, and deadly epidemics generated instability, deepening Pueblo frustrations and weakening traditional structures of authority.

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680

Coordinated Indigenous Resistance

In 1680, the Pueblo peoples launched one of the most successful Indigenous uprisings in North American history. The revolt—organized under the leadership of Popé, a Tewa religious leader—sought to expel the Spanish and restore Indigenous autonomy.

Popé: A Tewa Pueblo religious leader who organized and coordinated the 1680 uprising against Spanish rule in New Mexico.

The rebellion unified multiple Pueblo communities, who coordinated attacks on missions, isolated settlements, and colonial officials. Approximately 400 Spaniards were killed, including missionaries, and survivors fled south to El Paso.

Temporary Restoration of Pueblo Independence

For more than a decade, the Pueblos lived free from Spanish rule. They revived religious ceremonies, rebuilt kivas, redistributed land, and reestablished traditional leadership.

Ruins of a great kiva at Chetro Ketl in Chaco Canyon, illustrating the form and function of subterranean ceremonial spaces in Pueblo religious life. Such structures reveal why Spanish missionaries targeted kivas before 1680 and why their survival afterward symbolized renewed cultural autonomy. The site predates the Pueblo Revolt chronologically but accurately represents the architectural tradition discussed in the notes. Source.

Spanish Return and the Shift in Colonial Policy

The Spanish Reconquest of 1692

Spain, motivated by imperial competition and the desire to restore authority, reentered New Mexico in 1692 under Governor Diego de Vargas. Although his initial reoccupation involved negotiation and promises of clemency, resistance resurfaced periodically, and military action accompanied Spain’s return. Nevertheless, the reconquest was far less coercive than pre-1680 colonization, reflecting lessons learned from the revolt.

Accommodation and Cultural Flexibility

The AP syllabus emphasizes that American Indian resistance pushed Spain to accommodate some Indigenous cultural practices. After 1692, Spanish authorities modified their approach in several ways:

Reduced religious repression, allowing certain ceremonies and permitting the rebuilding of kivas.

Less intrusive missionary presence, with friars instructed to avoid harsh punishments and forced labor.

Local self-governance, as Pueblo leaders retained more authority over internal affairs.

Land protections, including recognition of Pueblo land grants that secured communities from encroaching settlers.

These accommodations were pragmatic, meant to stabilize Spain’s position in a contested region rather than representing ideological change. Still, they created a colonial system that blended Spanish and Pueblo practices more than before.

Continued Colonial Goals

Even with accommodations, Spain continued efforts to colonize the region, maintaining missions, presidios, and tribute systems.

Mission San Francisco de la Espada illustrates the architectural and institutional presence of Spanish missions in the broader Southwest. Such structures represent the persistent role of Catholicism and Spanish authority even after Indigenous uprisings like the Pueblo Revolt. This particular mission is in Texas and dates slightly later, providing a regional variation of the mission system discussed in the notes. Source.

The Spanish Crown viewed the Southwest as a defensive buffer against French and later American expansion, keeping political and military control a top priority. Cultural accommodation coexisted with ongoing demands for labor, trade cooperation, and political allegiance.

Long-Term Legacies of the Pueblo Revolt

Transformation of Spanish-Indigenous Relations

The revolt fundamentally altered Spanish strategies in the Borderlands. Officials recognized that harsh repression could trigger widespread resistance and therefore adopted policies built on negotiation, compromise, and shared practices. This helped sustain Spanish presence in New Mexico for more than a century afterward.

Strengthening Pueblo Cultural Autonomy

Pueblo communities gained more room to maintain religious rituals, communal landholding, and traditional governance. The blending of Catholicism with Indigenous spiritual practices resembled forms of syncretism, a cultural fusion shaped by both survival and adaptation.

Broader Regional Significance

The Pueblo Revolt influenced other Indigenous groups by demonstrating that colonial powers could be successfully resisted. It also shaped Spanish frontier policy across the Southwest, encouraging more diplomatic strategies with groups such as the Apache, Navajo, and Comanche. Spain increasingly relied on trade, alliances, and negotiated agreements—an approach rooted in what the revolt had revealed about the limits of coercion.

Enduring Cultural and Political Impact

The coexistence of Spanish and Pueblo traditions that emerged after 1680 endures in the Southwest today. Architectural forms, agricultural practices, religious ceremonies, and linguistic exchanges reflect the more flexible colonial order developed after the revolt. Politically, Pueblo land rights—supported by Spanish land grants and later confirmed by U.S. legal frameworks—trace their origins to post-revolt accommodation.

FAQ

The revolt relied on cooperation between Pueblo groups that historically maintained distinct languages, leadership structures, and rivalries. Shared grievances against Spanish rule helped unify them temporarily.

However, coordination varied by community, and some Pueblos participated more actively than others.

• The Tewa and Tiwa communities were among the most central in organising the uprising.

• Divergent local conditions influenced the level of commitment, contributing to challenges in sustaining unity after the Spanish fled.

Severe droughts and crop failures in the late seventeenth century intensified pressure on Pueblo communities. These hardships were made worse by Spanish demands for labour and tribute.

Environmental stress also undermined traditional religious practices tied to agriculture, heightening conflict with missionaries who banned ceremonies intended to restore balance.

The resulting instability made communities more receptive to Popé’s message of restoring spiritual and ecological harmony.

New Mexico lacked the mineral wealth of central New Spain, but it served key strategic purposes.

• It acted as a northern defensive buffer against French encroachment.

• Control of the region reinforced Spain’s territorial claims and imperial prestige.

Missionaries also argued that abandoning New Mexico would represent a retreat from Spain’s spiritual mission, strengthening the case for reconquest.

The revolt revealed the vulnerability of Spanish authority, prompting officials to reconsider relationships with neighbouring groups such as the Apache and Navajo.

After re-establishing control, Spain:

• pursued trade diplomacy to reduce hostilities,

• offered peace agreements in exchange for settlement near missions,

• and sought to prevent alliances between these groups and the Pueblos.

These policies reflected broader frontier adjustments shaped by the lessons of 1680.

Post-revolt accommodation fostered hybrid cultural forms visible in architecture, religious expression, and community governance.

Examples include:

• Pueblo Catholicism that incorporated Indigenous rituals alongside Christian observances,

• building styles combining Spanish masonry with Pueblo spatial designs,

• and communal landholding integrated into the colonial legal system.

These adaptations allowed Pueblo communities to retain core traditions while navigating renewed Spanish rule.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 changed Spanish colonial policy in the Southwest.

Question 1

• 1 mark for identifying a valid change in Spanish colonial policy (e.g., reduced religious repression, recognition of Pueblo leaders, or accommodation of Indigenous practices).

• 1 mark for describing how this change differed from pre-1680 policies (e.g., contrast with previous harsh missionary control or suppression of ceremonies).

• 1 mark for explaining why Spain adopted such policies (e.g., to prevent future uprisings, maintain stability, or rebuild alliances).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of the period 1607–1754, evaluate the extent to which the Pueblo Revolt represented a turning point in relations between the Spanish and Indigenous peoples in the Southwest.

Question 2

• 1–2 marks for a clear argument about the extent to which the Pueblo Revolt constituted a turning point (e.g., significant change vs. limited continuity).

• 1–2 marks for accurate and relevant evidence (e.g., Spanish accommodation of cultural practices, return under de Vargas, continued colonial ambitions).

• 1–2 marks for explanation linking evidence to the argument, showing how the revolt reshaped or failed to reshape Spanish–Indigenous relations.

Answers addressing both change (post-revolt accommodation and recognition of Pueblo autonomy) and continuity (Spain’s continued efforts to colonise the region) may score at the top of the range.