AP Syllabus focus:

‘Religious and ethnic diversity fostered pluralism and intellectual exchange in the colonies, creating a foundation for new cultural and political ideas in British North America.’

Early British America witnessed growing religious and ethnic diversity, encouraging cross-cultural interaction and expanding the exchange of ideas that shaped emerging political and cultural identities.

Pluralism in the British Colonies

Pluralism—the coexistence of multiple cultural, ethnic, and religious groups within a society—developed unevenly but significantly across British North America. Colonists encountered Indigenous peoples, Africans (both enslaved and free), and a widening array of European migrants, which generated new forms of social negotiation.

Pluralism: A social condition in which diverse cultural, religious, or ethnic groups maintain their unique practices while participating in a shared society.

This pluralistic environment encouraged colonists to rethink assumptions about authority, identity, and community belonging. While not all groups enjoyed equal status or freedom, the very presence of diversity required colonists to engage with unfamiliar beliefs and customs.

Sources of Religious Diversity

Religious variety expanded due to both intentional migration and the loosening enforcement of religious conformity.

Puritans, Anglicans, Quakers, Baptists, and Presbyterians brought differing theologies and worship practices.

Tolerance policies in colonies such as Rhode Island and Pennsylvania attracted dissenters from more restrictive regions.

Encounters with Indigenous spiritual traditions broadened colonists’ awareness of non-Christian cosmologies.

African religious practices, often blended with Christianity, persisted despite enslavement.

These varied traditions created an environment where debates over doctrine, morality, and community norms became part of everyday life.

Ethnic Diversity and Cultural Exchange

Ethnic pluralism deepened through continuous migration. Groups such as the Scots-Irish, Germans, Dutch, French Huguenots, and enslaved Africans added linguistic, cultural, and social complexity to colonial settlements.

Diverse languages and customs generated new hybrid practices in foodways, architecture, and communal life.

Trade relationships among different groups required negotiation across cultural boundaries.

Family networks, intermarriage in certain regions, and shared labor systems shaped distinctive local cultures.

The cumulative effect was a colonial society that relied increasingly on interaction rather than uniformity.

Intellectual Exchange in a Transatlantic World

Pluralism provided fertile ground for growing intellectual vitality. Colonists accessed ideas circulating across the Atlantic while also contributing local experiences to broader debates.

Print Culture and the Spread of Ideas

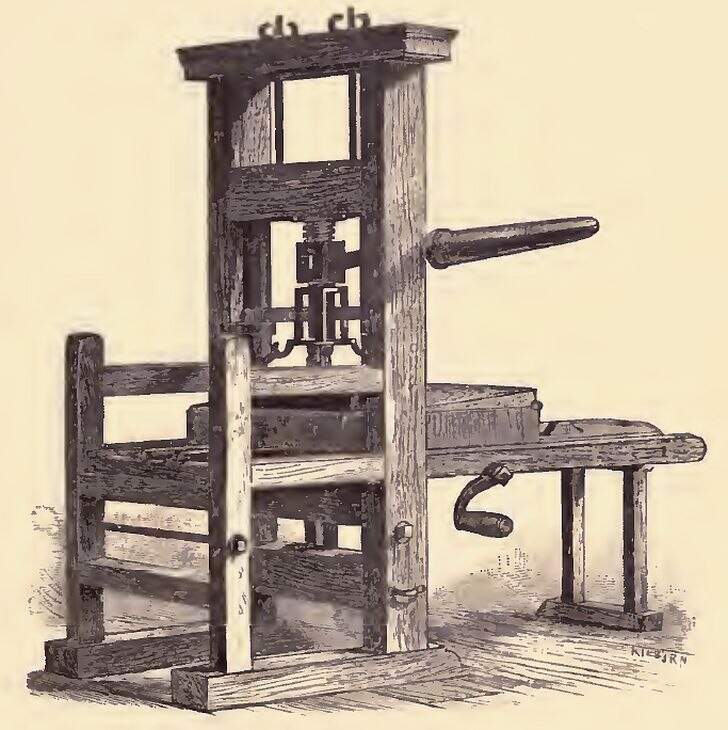

The expansion of printing presses, newspapers, pamphlets, and public libraries enabled ideas to circulate widely.

Newspapers reported on political developments, scientific discoveries, and religious controversies.

Pamphlets offered platforms for theological disputes, civic debates, and reform proposals.

Printed sermons and tracts allowed ministers and laypeople to participate in transcolonial discussions.

These networks strengthened colonists’ sense of belonging to a wider intellectual community.

Exchanges Through Trade, Travel, and Institutions

Beyond print, everyday interactions fostered intellectual growth.

Merchants shared news and innovations acquired through Atlantic trade.

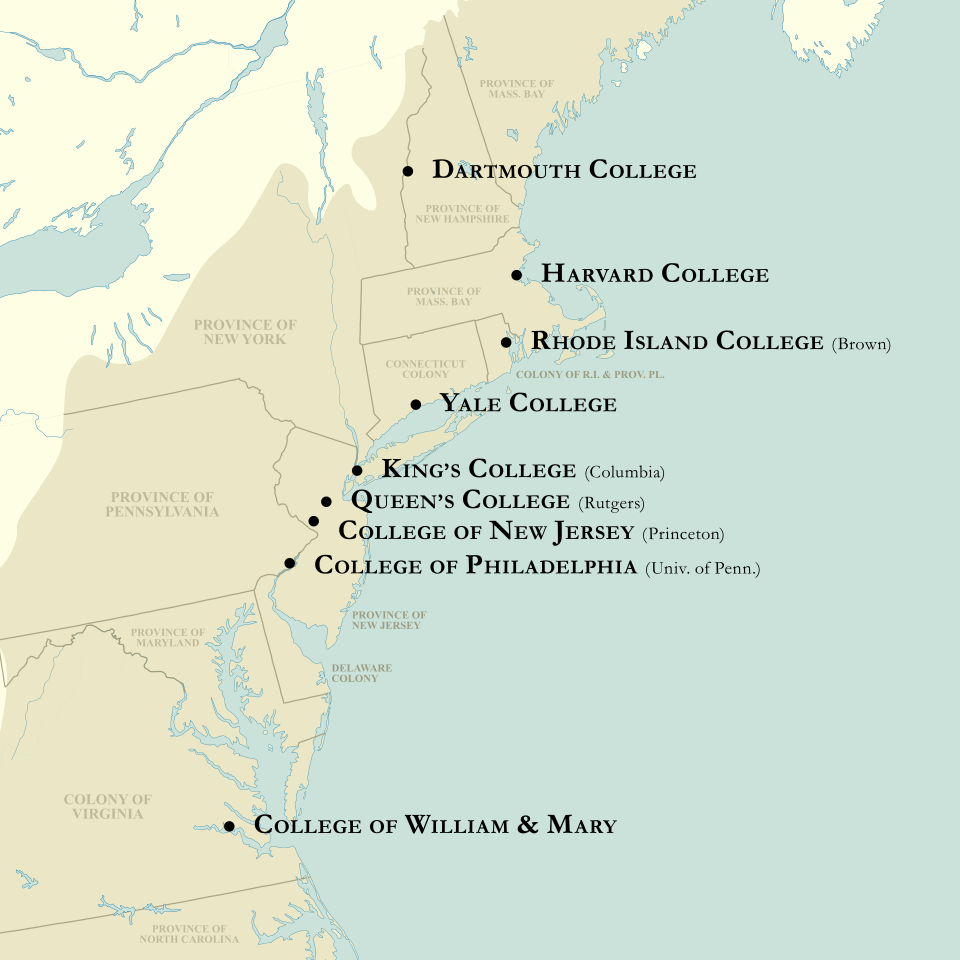

Colleges such as Harvard, Yale, and William & Mary promoted classical learning and stimulated scholarly discussion.

Urban centers like Boston, Newport, Philadelphia, and Charleston became hubs where artisans, merchants, and thinkers met.

This circulation of people and information accelerated the development of shared cultural frameworks.

Intersections of Diversity and Intellectual Life

Pluralism did not operate separately from intellectual exchange; instead, each reinforced the other.

Religious Debates and New Social Ideas

As colonists encountered theological diversity, they developed new approaches to authority and belief.

Dissenting groups challenged established churches, encouraging ideas about religious liberty and freedom of conscience.

Dialogue among competing denominations fostered a more participatory religious culture.

Minority groups’ demands for recognition influenced emerging conceptions of rights.

These exchanges gradually shaped political thought, even long before revolutionary tensions arose.

Ethnic Pluralism and Adaptation

Ethnic diversity influenced intellectual life by introducing alternative worldviews and practical knowledge.

German and Scots-Irish settlers contributed agricultural, artisanal, and communal traditions that differed from English norms.

African cultural retention—through music, oral traditions, and spirituality—created new cultural forms and contributed to evolving American identities.

Indigenous knowledge systems shaped colonial understandings of environment, diplomacy, and trade.

Such encounters demonstrated that intellectual exchange was not limited to elite institutions but was embedded in daily interactions.

Emerging Foundations for New Ideas

The combination of pluralism and intellectual exchange generated conditions under which new cultural and political ideas could emerge.

The presence of multiple religious groups undermined the assumption that a single established church should dominate civic life.

Interethnic interactions challenged rigid hierarchical assumptions and prompted discussions about inclusion, governance, and representation.

Increasing access to print culture encouraged colonists to compare their experiences with European debates on liberty, natural rights, and governance.

As communities became more accustomed to diversity and open argumentation, they established patterns of discussion, debate, and civic participation that later proved essential to the development of British North American political culture.

This map shows major institutions of higher learning in British North America by 1776, including Harvard, Yale, the College of New Jersey (Princeton), and William & Mary. These colleges served as regional centers for advanced study and intellectual exchange across the colonies. The map includes a few institutions founded slightly after 1754 but accurately reflects the developing college network that underpinned colonial intellectual life. Source.

Pluralism and Intellectual Exchange Continued

These patterns formed a cultural infrastructure that supported the later spread of Enlightenment and evangelical ideas, as well as early political thought about rights and government, shaping the trajectory of British North America well before independence.

Continued Print Culture and Broader Exchange

“Newspapers, pamphlets, and almanacs printed in towns such as Boston, Philadelphia, and New York allowed colonists to share news, argue about politics and religion, and participate in a growing colonial public sphere.”

This nineteenth-century illustration depicts James Franklin’s Ramage hand printing press, similar to presses used in early eighteenth-century Boston. Presses like this produced newspapers, almanacs, sermons, and political pamphlets that circulated across the colonies. Although the illustration dates from 1881, it portrays an earlier style of press typical of colonial British America and helps visualize the technology behind expanding print culture. Source.

Cross-Cultural Religious Engagement

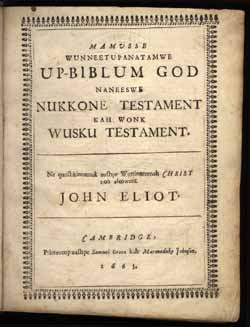

“Missionaries and Indigenous communities sometimes met in a shared intellectual space, as when Christian texts were translated into Native languages to spread scripture and debate belief.”

This image shows the title page of the 1663 Eliot Indian Bible, printed in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with text in the Massachusett (Wôpanâak) language. As the first Bible printed in British North America, it illustrates how religious ideas crossed linguistic boundaries and how Indigenous languages became part of the colonial print world. The page includes additional bibliographic detail beyond the AP syllabus but highlights the link between religious pluralism, translation, and intellectual exchange. Source.

FAQ

Urban centres acted as concentrated hubs where printers, merchants, clergy, and artisans interacted daily, allowing ideas to circulate faster than in rural areas.

These towns hosted coffeehouses, reading rooms, and bookshops where newspapers and pamphlets were shared and debated.

They also attracted migrants from diverse backgrounds, increasing exposure to different cultural and religious perspectives, which in turn stimulated discussion and experimentation in political and social thought.

Multilingualism expanded access to information by enabling the translation and circulation of texts across cultural groups.

It also encouraged colonists to adopt or adapt vocabulary, diplomatic terms, and concepts from Indigenous, African, and non-English European languages.

In areas like the middle colonies, multilingual environments required negotiation across linguistic boundaries, fostering skills in mediation and cross-cultural communication that strengthened intellectual interaction.

Women often engaged indirectly through domestic reading circles, religious gatherings, and household-based instruction.

Some acted as printers, booksellers, or contributors to family-run presses, influencing what material reached colonial audiences.

In diverse communities, women exchanged cultural knowledge—such as healing practices, childrearing methods, and religious traditions—creating informal intellectual networks not visible in official institutions.

Yes. Legal systems in pluralistic colonies sometimes accommodated multiple customs, particularly in commercial and land-use disputes involving non-English groups.

Courts in places like New York and Pennsylvania occasionally recognised linguistic differences, using interpreters or allowing translated testimony.

Over time, exposure to varied legal traditions contributed to broader colonial debates about rights, toleration, and the limits of authority.

Indigenous knowledge informed colonial understanding of governance, diplomacy, and environmental management.

Some colonists observed the political structures of nations such as the Haudenosaunee, which influenced debates about confederation and collective decision-making.

Indigenous ecological knowledge—seasonal cycles, land stewardship, and resource management—challenged European assumptions and enriched colonial intellectual life in subtle but enduring ways.

Practice Questions

Explain one way in which religious diversity contributed to intellectual exchange in the British colonies during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. (1–3 marks)

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark

Identifies a valid way religious diversity contributed to intellectual exchange.

(e.g., presence of multiple denominations encouraged debate; dissenters promoted discussions about liberty of conscience; varied beliefs increased circulation of printed theological material.)

2 marks

Provides a clear explanation of how this diversity fostered intellectual exchange.

(e.g., competing denominations published sermons and pamphlets that engaged wider audiences in discussions of doctrine and governance.)

3 marks

Develops the explanation with accurate supporting historical detail.

(e.g., citing colonies such as Pennsylvania or Rhode Island; noting how religious dissent contributed to broader conversations about authority and rights.)

Evaluate the extent to which ethnic and religious pluralism shaped the development of new cultural and political ideas in the British North American colonies before 1754. (4–6 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks

Presents a valid argument evaluating the impact of pluralism on cultural and political developments.

Provides at least some relevant supporting evidence.

(e.g., German, Scots-Irish, and African cultural influences; growth of colonial print culture; challenges to established churches.)

5 marks

Demonstrates a clearer, more sustained line of reasoning.

Uses well-selected evidence showing how pluralism shaped ideas (e.g., religious liberty, freedom of conscience, community governance, shared intellectual networks).

May reference specific examples such as Pennsylvania’s tolerance policies or the influence of colonial colleges.

6 marks

Offers a well-developed and balanced evaluation of the extent of pluralism’s impact.

Uses specific, accurate, and relevant evidence throughout.

Shows awareness of nuance or limitations (e.g., pluralism varied regionally; not all groups enjoyed equal freedoms; coexistence could also create tension).