AP Syllabus focus:

‘War between France and Britain after the French Revolution challenged U.S. free trade and foreign policy, and it intensified political disagreement at home.’

The French Revolution and resulting European wars forced the young United States to confront difficult diplomatic choices, shaping foreign policy debates, economic challenges, and emerging political divisions in the 1790s.

The French Revolution and Its Global Reverberations

The outbreak of the French Revolution (1789) transformed European politics and unsettled international economic systems.

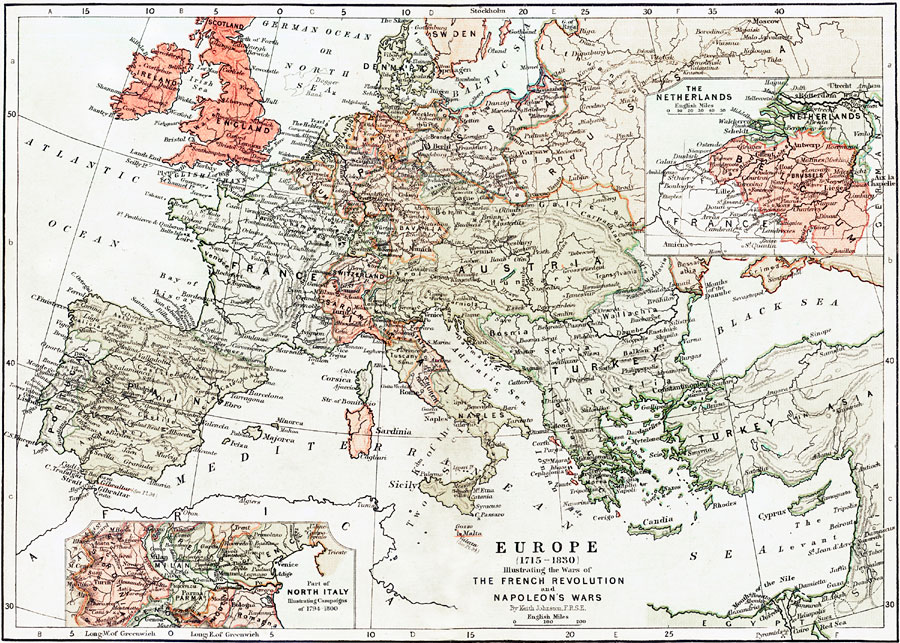

Map of Europe showing the major states and political boundaries during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars. It highlights the great-power alignments that shaped the global context influencing U.S. neutrality. The map contains additional geographic detail beyond AP requirements, but students should focus on the alignment of major powers. Source.

For the United States, the revolution created both ideological sympathy and strategic uncertainty, because Americans recognized parallels between French revolutionary ideals and their own recent struggle for independence. At the same time, escalating conflict between France and Britain, especially after 1793, threatened to draw the United States into a broader imperial war. As the nation lacked a strong military and depended heavily on Atlantic trade, such involvement posed significant risks.

U.S. Neutrality and Diplomatic Challenges

President George Washington adopted a policy of neutrality, asserting that the United States would maintain friendly relations with all nations while avoiding entanglement in their conflicts. Neutrality represented an effort to protect American commerce and prevent diplomatic crises that the fragile republic was ill-equipped to handle.

Neutrality: A foreign policy stance in which a nation avoids taking sides in conflicts between other states, seeking to preserve peace and economic stability.

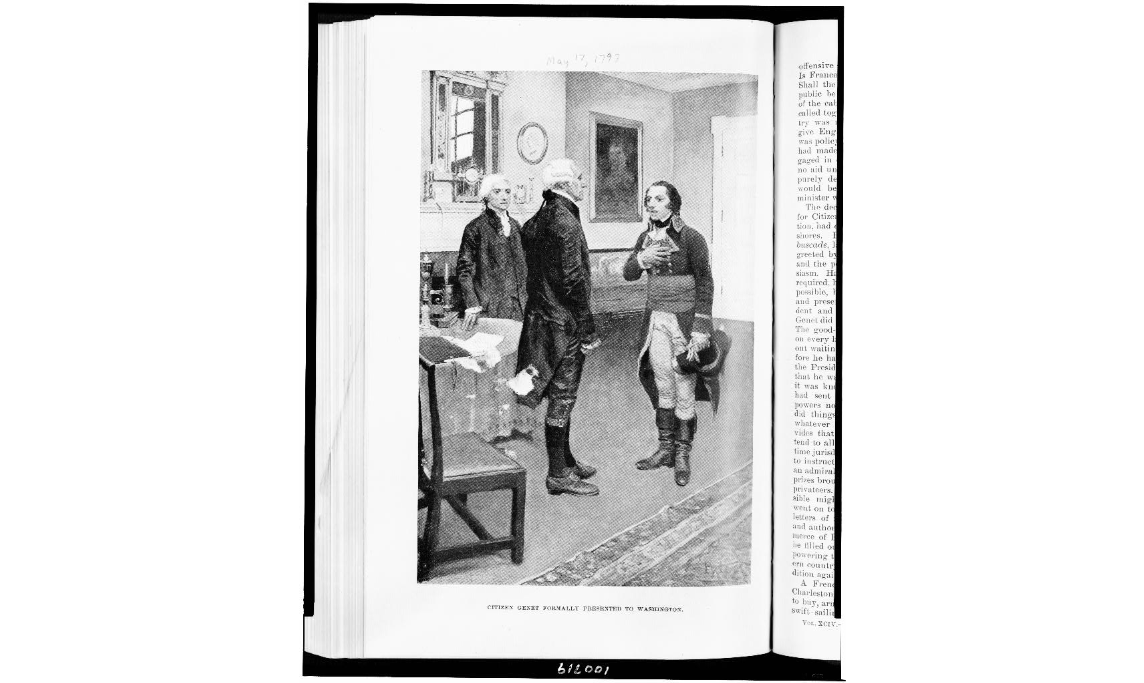

Washington’s Proclamation of Neutrality (1793) declared that the United States would not support either France or Britain in their ongoing war. Despite its clarity, the proclamation sparked intense debate, especially because France had helped the United States win independence and believed earlier treaties obligated American support. One key challenge emerged in the mission of Citizen Edmond Genêt, the French envoy who attempted to recruit American privateers, thereby violating U.S. sovereignty and testing the authority of the new federal government.

Howard Pyle’s illustration depicts French envoy Citizen Genêt being formally presented to President George Washington in 1793. The scene captures how revolutionary France attempted to influence American policy despite Washington’s neutrality. The artistic style includes embellishments beyond AP expectations, but the focus on Washington and Genêt remains historically useful. Source.

The Strain on American Trade and Commercial Rights

Neutrality was difficult to uphold because Britain and France each sought to disrupt the other’s trade. The British Royal Navy seized American ships suspected of carrying goods to France or its colonies. These seizures angered American merchants and threatened the nation’s economic welfare, as overseas commerce constituted a major portion of federal revenue.

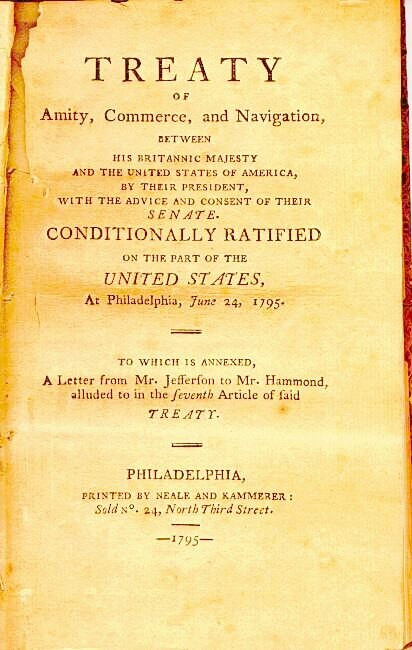

To address these tensions, Washington sent John Jay to negotiate a treaty with Britain. The resulting Jay’s Treaty (1794) secured limited commercial concessions and a British promise to evacuate forts in the Northwest Territory, but it failed to protect American neutral shipping rights fully.

Title page of the 1795 printing of Jay’s Treaty, formally named the “Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation” between the United States and Great Britain. The document symbolizes the controversy surrounding Federalist diplomacy and the struggle to preserve American neutrality. The page includes printer details not required for AP study but helps contextualize the treaty as a published public document. Source.

While the treaty kept the United States out of war, it deepened domestic divisions and intensified accusations that Federalists favored Britain over France.

Political Disagreement and the Rise of Party Conflict

The French Revolution became a defining issue in the emergence of America’s first political parties. Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, generally opposed the radical turn of the French Revolution and supported closer ties with Britain to promote trade and national stability. Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, viewed the French Revolution as a continuation of global struggles for liberty and accused Federalists of betraying republican principles.

Key Sources of Political Conflict

Foreign Policy Orientation

Federalists emphasized order and commercial ties with Britain.

Democratic-Republicans emphasized support for republican movements abroad and sympathy for France.

Domestic Power and Constitutional Interpretation

Disputes about neutrality contributed to broader disagreements over executive power and constitutional limits, as critics argued that the president lacked authority to issue such a proclamation without congressional approval.

Public Opinion and the Press

Newspapers affiliated with each party amplified disputes, portraying the opposing side as either dangerously radical or insufficiently committed to American independence.

The Whiskey Rebellion (1794) further shaped these debates by highlighting how domestic dissent and foreign affairs intersected. Many Democratic-Republicans suggested that Federalist leaders used foreign threats to justify stronger federal authority, while Federalists blamed unrest partly on French revolutionary ideas influencing American society.

The Broader Impact on U.S. Foreign Policy

The conflicts of the 1790s established foundational principles of American diplomacy. Washington’s neutrality stance signaled the desire to remain independent from European alliances, a theme echoed in later presidential addresses and diplomatic doctrines. Neutrality also forced the United States to define its commercial rights in a world dominated by European empires, laying the groundwork for future disputes involving maritime law and embargoes.

A normal sentence must appear here between definition blocks to satisfy formatting rules.

Free Trade: The ability of a nation’s merchants to conduct commerce without interference, seizure, or discriminatory restrictions imposed by foreign powers.

Continuing Tensions and the Path Toward Partisanship

Although neutrality kept the young republic out of war, it did not resolve its underlying diplomatic vulnerabilities. When John Adams became president, French anger over Jay’s Treaty led to the Quasi-War (1798–1800), an undeclared naval conflict that further divided Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. These tensions revealed how profoundly the French Revolution and European warfare shaped internal U.S. political culture.

The controversies of the 1790s demonstrated that foreign affairs could generate intense domestic conflict, influence party development, and challenge the limits of federal authority. The struggle to balance neutrality, free trade, and political unity became a defining feature of early American governance, firmly rooted in the context of the French Revolution and transatlantic warfare.

FAQ

Early support stemmed from parallels with the American Revolution: opposition to monarchy, belief in popular sovereignty, and gratitude for French aid during the War of Independence.

As the revolution grew more radical, especially during the Reign of Terror, Federalists argued it threatened stability and order. Democratic-Republicans continued to emphasise shared republican ideals, deepening ideological divides in the United States.

Both Britain and France expanded their naval blockades, searching and seizing neutral vessels suspected of aiding the enemy. American ships were often caught in these escalating maritime restrictions.

This disruption increased insurance costs, slowed transatlantic shipping times, and forced merchants to modify trade routes. Some ports experienced temporary commercial decline due to uncertainty at sea.

Citizen Genêt actively attempted to recruit American privateers and organise military expeditions without Washington’s consent. This undermined the executive’s authority to determine foreign policy.

The incident prompted the administration to clarify diplomatic protocol, assert control over foreign agents, and reinforce the idea that the president—not individual states or private citizens—directed international relations.

For many citizens, the treaty appeared too conciliatory toward Britain, which had recently seized American ships and still occupied frontier forts.

Public protests reflected fears that the United States might drift back into economic or political dependence on Britain. Additionally, secrecy surrounding the negotiations fuelled suspicion that national interests were being compromised.

Neutrality debates encouraged politicians and activists to use newspapers to defend their positions and attack opponents.

This expanded the press’s political role and stimulated a surge in explicitly partisan publications.

Federalist papers stressed the need for order and alignment with Britain.

Republican papers emphasised liberty, civic virtue, and sympathy for France.

The result was a more engaged—but also more polarised—public sphere.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the French Revolution influenced political divisions within the United States during the 1790s.

Mark Scheme:

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a valid influence (e.g., the French Revolution intensified divisions between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans).

1 mark for describing how a specific issue or event contributed to these divisions (e.g., disagreements over whether to support France or maintain neutrality).

1 mark for explaining the broader political impact (e.g., the rise of organised parties as each side accused the other of endangering the nation’s security or republican values).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which the United States’ policy of neutrality in the 1790s was a successful response to the challenges posed by the war between France and Britain.

Mark Scheme:

Award up to 6 marks:

1 mark for a clear statement of judgement about the success or limitations of neutrality.

1 mark for explaining how neutrality helped avoid direct involvement in European conflict.

1 mark for referencing specific diplomatic actions (e.g., Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation, Jay’s Treaty).

1 mark for explaining how British or French interference with American trade created difficulties despite neutrality.

1 mark for discussing domestic consequences, such as increased party polarisation.

1 mark for a developed explanation showing balance or nuance (e.g., neutrality preserved peace but failed to protect neutral shipping fully and intensified political disputes).