AP Syllabus focus:

‘Conflicts over states’ rights, economic and foreign policy, and the balance between liberty and order led to political parties, including Hamilton’s Federalists and Jefferson and Madison’s Democratic-Republicans.’

The emergence of political parties in the 1790s reflected deep ideological clashes over federal power, economic development, and America’s position in a turbulent international environment.

Origins of Factional Division

The early republic did not initially expect formal political parties, which many leaders associated with corruption and disunity. Yet competing visions of national development created persistent disagreements. Key debates over the scope of federal authority, the structure of the economy, and the direction of foreign policy generated distinct political identities that solidified into two major groups.

After independence, leaders confronted new challenges: war debts, diplomatic uncertainty, regional differences, and the need to implement the Constitution’s flexible framework. These pressures pushed policymakers to articulate sharply different interpretations of national priorities and constitutional powers.

Hamilton’s Federalist Vision

Economic Policy as a Source of Conflict

Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton advanced plans to stabilize and strengthen the new nation.

This portrait by John Trumbull depicts Alexander Hamilton, the leading Federalist whose financial program helped define early partisan conflict in the 1790s. It visually anchors Hamilton’s central role in shaping a strong national government and commercial economy. The portrait does not show policy details but provides essential historical context for understanding Federalist leadership. Source.

His proposals—funding national debt at face value, assuming state debts, creating a national bank, and supporting manufacturing—sparked intense controversy.

Federalists: Supporters of a strong national government, commercial development, and Hamilton’s economic programs.

Hamilton’s system encouraged close ties between government and finance, which he believed would promote long-term national stability. Critics argued that these initiatives enriched wealthy speculators and expanded federal authority beyond constitutional limits. The resulting disputes revealed divergent interpretations of the necessary and proper clause, with Federalists favoring a broad, flexible reading.

One sentence of normal text appears here to follow formatting rules.

National Bank: A federally chartered institution designed to hold government funds, issue currency, and regulate financial activity.

Federalists contended that America required such an institution to manage credit and bind economic interests to the national government. Opposition centered on fears that the bank threatened state authority and favored urban elites.

Social and Political Characteristics

Federalists drew support from:

Northern merchants and financiers

Urban commercial centers

Individuals favoring energetic federal governance

They emphasized order, stability, and economic modernization, often aligning with British trading interests in foreign affairs.

Jefferson and Madison’s Democratic-Republican Vision

Commitment to Limited Federal Power

In response to Hamilton’s programs, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison articulated a competing ideology prioritizing agrarian independence and restrained federal authority.

This official portrait of Thomas Jefferson presents the central figure of the Democratic-Republican Party. It reinforces Jefferson’s ideological commitment to limited federal power, agrarianism, and strict constitutional interpretation. The portrait itself focuses on likeness rather than political ideas but offers essential visual context for the party’s leadership. Source.

Democratic-Republicans: Advocates of limited central government, agricultural interests, and strict adherence to the Constitution.

Jefferson argued that concentrated power threatened the liberty won in the Revolution. He believed that a republic depended on widespread landownership and the political virtue of independent farmers. Democratic-Republicans opposed policies that, in their view, privileged financial capitalism over agrarian citizens.

Regional and Social Support

Their base included:

Southern planters

Western farmers

Americans wary of centralized economic policies

These groups favored states’ rights and feared that Federalist programs imposed uniform national structures insensitive to local needs.

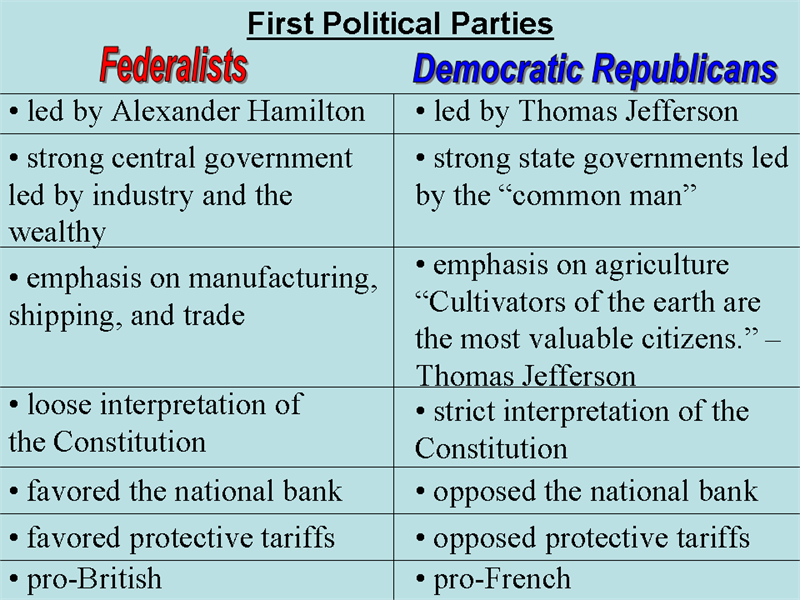

This chart compares Federalists and Democratic-Republicans across leadership, governmental power, economic priorities, and foreign policy alignment. It clearly illustrates how conflicts over states’ rights, economic direction, and international orientation shaped the first U.S. party system. The chart includes a quotation and minor extra detail not required by the syllabus but fully consistent with AP-level understanding. Source.

Foreign Policy Tensions and Their Partisan Impact

The French Revolution’s Polarizing Effects

Events abroad intensified domestic divides. The French Revolution, with its republican rhetoric and escalating violence, provoked conflicting reactions. Federalists condemned the revolution’s radicalism and leaned toward Britain, the United States’ largest trading partner. Democratic-Republicans welcomed the French movement as an extension of American revolutionary ideals and resented British restrictions on U.S. maritime trade.

Key foreign policy flashpoints included:

The Neutrality Proclamation (1793), which angered Democratic-Republicans

Jay’s Treaty (1795), seen by opponents as pro-British and overly conciliatory

Increasing maritime tensions with France, culminating in the Quasi-War

These disputes sharpened partisan identities and encouraged more organized political action.

Political Mobilization and the Institutionalization of Parties

Public Participation and Print Culture

The 1790s saw expanded political engagement. Citizens expressed partisan loyalties through:

Newspapers and pamphlets aligned with Federalist or Democratic-Republican interests

Political societies and informal campaign networks

Public meetings, petitions, and debates

The growth of a vibrant print culture enabled rapid circulation of political ideas and accusations. Partisan newspapers routinely attacked opponents’ motives, fostering a new, combative political climate.

The Election of 1796 and the Adams Presidency

By the mid-1790s, political parties had become essential components of national politics. The election of 1796—the first with competing party candidates—featured John Adams for the Federalists and Thomas Jefferson for the Democratic-Republicans. Adams’s presidency intensified polarization, especially through the Alien and Sedition Acts, which Democratic-Republicans condemned as assaults on civil liberties and partisan attempts to silence dissent.

Growing outrage encouraged Democratic-Republican organization at local and state levels, deepening party structures that would endure into the nineteenth century.

Balancing Liberty and Order

Conflicts over states’ rights, economic regulation, and foreign alignment drove the formation of the first American political parties. The 1790s demonstrated that divergent interpretations of constitutional authority and national purpose could not be resolved without formal political organization. Federalists emphasized order, national power, and commercial expansion, while Democratic-Republicans defended individual liberty, state sovereignty, and agrarian democracy.

FAQ

Many Americans associated political parties with corruption, instability, and the factional strife they believed had weakened earlier republics such as Rome.

They also feared that organised political groups would prioritise sectional or elite interests over the common good, undermining the unity necessary for the young nation’s survival.

George Washington’s public warnings against faction reinforced this cultural suspicion, making the rapid rise of parties seem both unexpected and concerning.

The North’s growing commercial and financial sectors tended to support Federalist policies, which promised stable credit, investment, and closer ties with Britain.

In contrast, the South and West, dominated by agriculture, preferred Democratic-Republican ideas that emphasised landownership, local autonomy, and suspicion of centralised finance.

These economic contr

Newspapers became powerful vehicles for partisan messaging, often funded or encouraged by leading figures in both parties.

Editors routinely published essays attacking opponents’ motives or portraying policies in highly ideological terms.

This created a national environment in which party identity became easier for ordinary voters to adopt, as political information was increasingly framed through partisan lenses.

Federalists tended to view political decision-making as a responsibility best handled by educated elites, whom they believed were less vulnerable to demagoguery.

Democratic-Republicans, although not democratic by modern standards, were more open to broader public involvement and believed that civic virtue resided widely among independent farmers.

These differing assumptions shaped debates over how inclusive the new political system should be.

The United States faced unresolved issues with both Britain and France, including trade restrictions, frontier tensions, and maritime rights.

Each diplomatic challenge forced leaders to articulate different visions of how the nation should navigate global power struggles.

Because these foreign pressures demanded clear strategic choices, they pushed American political leaders into more organised ideological camps, hastening party formation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which Alexander Hamilton’s financial programme contributed to the emergence of political parties in the 1790s.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a relevant aspect of Hamilton’s programme (for example, creation of the national bank, assumption of state debts, funding the national debt, or support for manufacturing).

1 mark for explaining why this aspect was controversial (for example, perceived expansion of federal power, privileging financiers, undermining states’ rights).

1 mark for linking the controversy to the rise of political parties (for example, explaining how opponents coalesced into the Democratic-Republicans while supporters formed the Federalists).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which disagreements over foreign policy were responsible for the development of Federalist and Democratic-Republican political identities in the 1790s.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks:

1–2 marks for correctly identifying relevant foreign policy issues (for example, the French Revolution, neutrality debates, Jay’s Treaty, maritime tensions with France).

1–2 marks for explaining how these issues divided political leaders or the public (for example, Federalist support for Britain, Democratic-Republican sympathy for France, disagreements over whether the United States should engage in European conflicts).

1–2 marks for analysing the extent of foreign policy’s role in shaping party identities, which may include a balanced argument acknowledging additional factors (such as economic policy disagreements, constitutional interpretation, or sectional interests).

Top-mark answers will provide a clear analytical judgement about the degree to which foreign policy disputes, compared with other factors, drove the formation of the first party system.