AP Syllabus focus:

‘An unclear relationship between the federal government and American Indian tribes produced disputes over treaties and legal claims connected to the seizure of Indigenous lands.’

Federal–Indigenous relations after independence were shaped by ambiguous legal status, competing land claims, and expanding settlement pressures, creating conflict over sovereignty, treaties, and the federal government’s authority to regulate territorial expansion.

Federal Authority, Tribal Sovereignty, and Legal Ambiguity

The early republic confronted major tensions as the federal government attempted to define its relationship with Indigenous nations while settlers pushed aggressively westward.

Map showing major Native nations in the Northwest Territory around 1792, illustrating the complex distribution of Indigenous homelands in a region contested by the United States. It highlights overlapping territorial claims that contributed to diplomatic tensions. The map includes some additional tribal labels beyond those required by the syllabus. Source.

The Constitution granted the federal government authority over diplomacy and Indian affairs, yet it did not clearly define tribal sovereignty or the limits of federal versus state control. This ambiguity allowed different political actors to interpret Indigenous rights according to their economic or political interests.

Tribal Sovereignty: The inherent authority of Indigenous nations to govern themselves and manage their internal affairs.

Although the federal government generally recognized tribes as distinct political communities capable of making treaties, many states rejected this framework. Georgia and other southern states, for example, challenged federal authority by asserting that Indian lands lay within their boundaries and were therefore subject to state jurisdiction. This conflict over sovereignty destabilized negotiations and contributed to inconsistent policy enforcement.

Following this, U.S. leaders increasingly viewed Native land as necessary for national growth. The pressure to satisfy settlers and land speculators often outweighed treaty commitments, creating a pattern in which federal–Indigenous relations became entangled with expansionist goals.

Treaties, Diplomacy, and Conflicts over Land

Treaty-making was the federal government’s primary method of managing relations with Indigenous nations, but treaty agreements often reflected unequal power dynamics. Many treaties followed military conflicts or were negotiated under coercive circumstances, reinforcing U.S. advantage. Even when treaties pledged to protect Indigenous territorial rights, these commitments frequently eroded under political and economic pressure.

Treaty: A formal agreement between sovereign powers; in this context, between the U.S. government and an Indigenous nation outlining land ownership, boundaries, and mutual obligations.

Treaties also varied widely in clarity and enforcement. Because treaty language sometimes contradicted previous agreements or ignored established land use, Indigenous leaders faced constant challenges to defend territorial claims. Disputes intensified when multiple tribes claimed overlapping rights to regions targeted by American settlers.

The Treaty of Greenville (1795), signed after conflicts in the Northwest Territory, illustrated these dynamics.

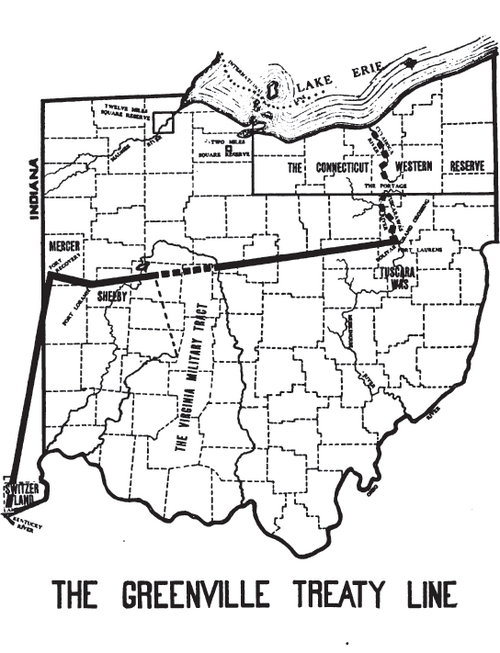

Map of Ohio after the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, showing how the treaty divided Indigenous land from areas newly opened to U.S. settlement. The visual boundary clarifies the scale of land cession required by the agreement. The map focuses specifically on Ohio and does not depict all regions involved in broader federal–Indigenous conflicts. Source.

It forced major land cessions after Native defeat but also acknowledged limited Indigenous control over remaining territory. Although intended to stabilize relations, the treaty ultimately encouraged further settlement, setting off additional demands for land.

Land Seizures and the Expansionist Context

As migration westward increased after independence, federal–Indigenous tensions escalated, driven by U.S. desires to secure land for agriculture, commerce, and national development.

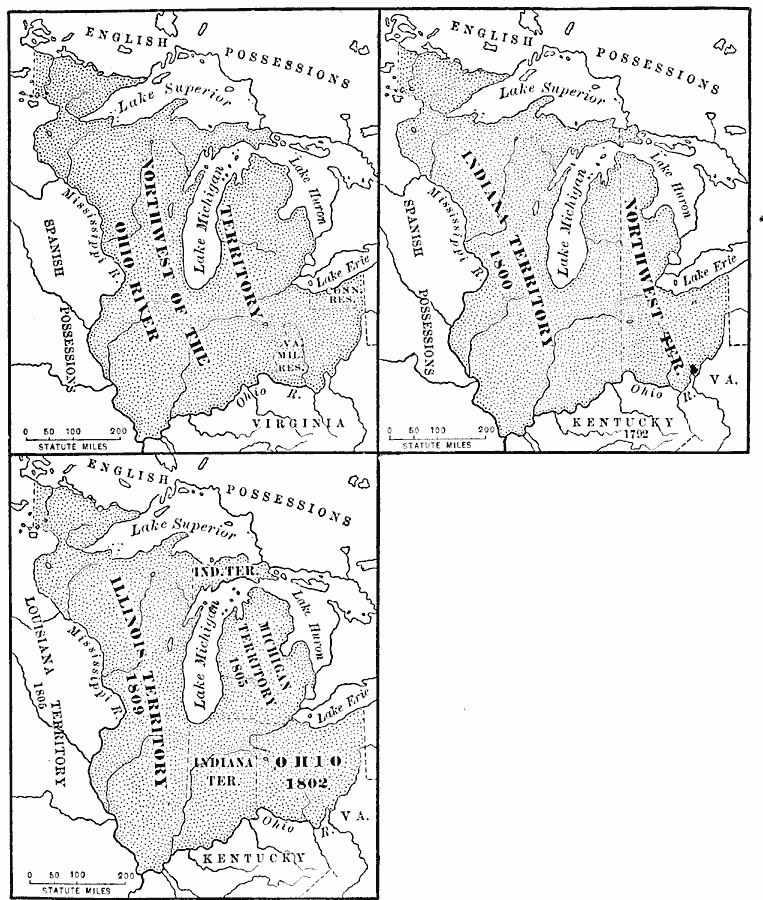

Three-panel map showing territorial changes in the Northwest Territory from 1790 to 1810, illustrating how U.S. administrative boundaries expanded across Indigenous homelands. It provides visual context for how federal policies, migration, and treaty-making shaped western territory. Some geopolitical details extend slightly beyond the strict AP focus but support understanding of regional transformation. Source.

Land seizures took multiple forms:

Treaty cessions obtained through coercion, military pressure, or negotiations that favored U.S. interests.

Illegal settlement, in which frontier settlers occupied Native land prior to federal approval, forcing authorities to decide whether to remove settlers or negotiate new land transfers.

State-level claims, especially in the South, where officials argued that tribes could not hold land independently within state boundaries.

Military campaigns, used when Indigenous resistance was framed as a threat to U.S. security or commerce.

These processes blurred the distinction between diplomatic agreements and forceful dispossession. The absence of a consistent legal framework for Indigenous land rights enabled federal and state governments to treat Native occupation as temporary or negotiable. The drive for land, rather than stable relations, often dictated policy outcomes.

Federal Policy Experiments and Their Consequences

The Washington administration attempted to impose greater order on federal–Indigenous relations by emphasizing diplomacy and regulated trade. Policies aimed to centralize control of negotiations and reduce conflicts caused by local officials or settlers. Despite these efforts, federal enforcement remained uneven, especially when political leaders sought to appease expansion-minded constituents.

Key features of early policy included:

The Trade and Intercourse Acts, which required federal approval for land cessions and attempted to regulate interactions between settlers and tribes.

Boundary lines, drawn to protect Native territory but frequently violated or redrawn as new treaties were negotiated.

Military interventions, used when diplomacy failed or when the government sought to compel compliance with U.S. demands.

Promotion of “civilization” programs, which encouraged Indigenous adoption of Euro-American farming practices and gender roles in hopes of transforming tribal societies and facilitating land acquisition.

While officials described these policies as protective or benevolent, they often undermined tribal autonomy. Programs aimed at cultural transformation created additional pressure for Indigenous communities to conform to U.S. expectations or risk further land loss.

Legal Claims, Sovereignty Disputes, and the Path Toward Removal

The uncertain legal relationship between tribes and the federal government shaped ongoing disputes over land claims. Because Indigenous nations were not clearly recognized as fully sovereign foreign powers or as domestic dependents with protected rights, they lacked secure legal standing. This ambiguity made it easier for U.S. policymakers to reinterpret obligations as political circumstances changed.

Conflicts over sovereignty and land during this period laid the groundwork for more aggressive 19th-century policies. Although the formal removal era came later, the patterns of treaty violation, territorial pressure, and contested authority established in the 1790s normalized the idea that Indigenous land could be seized whenever deemed necessary for national development.

FAQ

Many Indigenous nations viewed treaties as agreements between equal sovereign powers that established mutual obligations and affirmed long-term territorial rights.

U.S. officials, however, often treated treaties as temporary arrangements subject to revision when political or economic goals shifted.

Because Indigenous diplomacy emphasised kinship, reciprocity, and negotiated coexistence, the federal government's more rigid legalistic approach frequently caused misunderstandings and disputes.

Land companies and private investors lobbied federal leaders to open western territory, presenting expansion as vital to national prosperity.

Their influence mattered because:

They helped finance early American political figures.

They shaped public narratives portraying Indigenous land as underused.

They pressured Congress to approve treaties favourable to private land acquisition.

This economic lobbying undermined diplomatic commitments to Indigenous nations.

States such as Georgia feared that recognising Indigenous sovereignty would limit their own territorial expansion and weaken their political authority.

They also argued that, since tribes lived within state borders, states had the right to regulate land sales and legal matters.

This resistance created a structural conflict between state claims and the Constitution’s assignment of Indigenous diplomacy to the federal government.

Many tribes formed confederacies to coordinate diplomacy, share intelligence, and resist land loss more effectively.

For example:

Councils brought together leaders from different nations to agree on unified strategies.

Confederacies attempted to insist that no land could be ceded without joint approval.

Shared military action increased leverage in negotiations.

These efforts reflected long-standing traditions of intertribal alliances.

Garrisons acted as symbols of federal authority, providing logistical bases for diplomacy, surveillance, and enforcement.

They also:

Facilitated trade regulation by monitoring goods moving through frontier regions.

Protected settlers, encouraging further migration into contested territory.

Pressured Indigenous nations by demonstrating the federal government’s ability to mobilise force.

Their presence often escalated tensions even when no active conflict occurred.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one reason why relations between the federal government and Indigenous nations were unclear in the early United States, and briefly explain how this contributed to land disputes.

Question 1

Award marks as follows:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason for unclear federal–Indigenous relations.

Examples:The Constitution did not clearly define tribal sovereignty.

Conflicts between federal and state authority over Indigenous affairs.

Overlapping land claims by settlers and tribes.

1 mark for explaining how this lack of clarity contributed to disputes.

Examples:States challenged federal authority, creating competing claims.

Ambiguous sovereignty made treaty enforcement inconsistent.

1 additional mark for specific or developed explanation.

Examples:Mention of Georgia or southern states asserting control over Indigenous lands.

Reference to settlers occupying land illegally due to weak federal enforcement.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how federal policies and settler expansion shaped the seizure of Indigenous lands between 1783 and 1800. In your answer, refer to both federal attempts to regulate relations with Indigenous nations and pressures that undermined those efforts.

Question 2

Award marks as follows:

1–2 marks for explaining how federal policies attempted to manage relations with Indigenous nations.

Examples:Reference to the Trade and Intercourse Acts.

Federal treaty-making efforts intended to regulate land cessions.

Washington administration attempts at diplomacy.

1–2 marks for explaining how settler expansion pressured land loss.

Examples:Illegal settlement forcing new treaties.

Rising demands for farmland in the Northwest Territory.

Military conflict leading to coerced cessions.

1–2 marks for integrating both federal policy and settler actions into a coherent argument or for providing specific historical evidence.

Examples:Treaty of Greenville (1795) as an example of land cession following military defeat.

Discussion of conflicting state and federal priorities.

Demonstrating how federal attempts at control were undermined by expansionist pressures.