AP Syllabus focus:

‘Delegates from the states met at the Constitutional Convention and, through negotiation and compromise, proposed a new constitution to replace the Articles of Confederation.’

Delegates gathered in Philadelphia in 1787 to address the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, ultimately forging an innovative constitutional framework through debate, negotiation, and strategic compromise.

The Constitutional Convention Begins

The Constitutional Convention convened in May 1787 in Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania State House, with fifty-five delegates representing twelve states (Rhode Island abstained).

This painting depicts George Washington presiding over the Philadelphia Convention as delegates gather to sign the Constitution. It conveys the atmosphere of formal debate and collective decision-making that defined the meeting. The artwork includes more figures and artistic detail than required by the syllabus but effectively visualizes the convention environment. Source.

with fifty-five delegates representing twelve states (Rhode Island abstained). These delegates, later known collectively as the Framers, met originally to revise the Articles of Confederation. However, widespread agreement emerged that the Articles’ structure—particularly its weak central authority—was inadequate for governing a growing and economically strained nation.

Many delegates arrived with differing regional interests, political philosophies, and visions for the republic’s future. Their ability to reach common ground depended on shared commitments to republicanism, the rule of law, and preserving the Union. Still, conflict was unavoidable, necessitating significant negotiation.

Key Proposals and the Emergence of Debate

Early in the convention, the Virginia Plan and the New Jersey Plan revealed deep divisions over representation and the scope of national power.

Virginia Plan: A proposal favoring large states by calling for a bicameral legislature with representation based on population.

After this proposal initiated extensive debate, delegates from smaller states sought alternatives.

New Jersey Plan: A proposal maintaining a unicameral Congress with equal representation for each state, preserving more authority for state governments.

These competing plans illustrated the convention’s fundamental problem: how to balance state and national power while ensuring fair representation for both large and small states. Delegates recognized that unity required compromise on these competing visions.

The Great Compromise

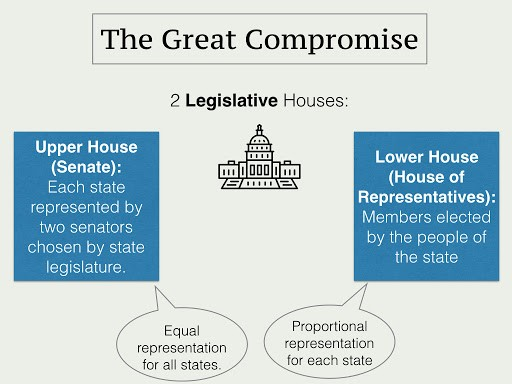

The Great Compromise (also known as the Connecticut Compromise) became one of the convention’s most crucial achievements.

This diagram illustrates the bicameral structure created by the Great Compromise, with equal state representation in the Senate and proportional representation in the House. It clarifies how elements of both the Virginia and New Jersey Plans were blended to resolve conflict between large and small states. The diagram includes additional historical details, such as selection methods, which extend slightly beyond the syllabus but help contextualize the compromise. Source.

Crafted primarily by Roger Sherman of Connecticut, it blended the competing proposals and eased sectional tensions. Its major components included:

A bicameral legislature

House of Representatives with representation based on population

Senate with equal representation for each state (two senators per state)

Direct election of House members, with state legislatures initially selecting senators

This structure struck a balance between populous and smaller states, preventing domination by either group. It also laid the foundation for a stronger federal government while preserving state influence.

A single legislative structure might have doomed the new government, making this compromise essential to forming a workable constitutional system.

Debates over Executive Power

Another key area of negotiation centered on establishing a national executive. Delegates debated whether the executive should be a single individual or a committee, how long the term should last, and who should elect the executive. Many worried about creating a position that resembled monarchical authority.

The resulting agreement established:

A single executive titled the President

A renewable four-year term

Selection through an Electoral College, balancing popular input with state influence

Powers including commander-in-chief authority, treaty negotiation (with Senate approval), and veto capability

These negotiations reflected concerns about preventing tyranny while ensuring the government possessed enough energy and leadership to function effectively.

Judicial Structure and Federal Authority

Delegates also needed to determine the nature of the national judiciary and how federal laws would interact with state laws. Disputes arose over the extent of judicial review, the creation of lower federal courts, and the role of state courts.

Compromises included:

Establishing a Supreme Court with authority over federal questions

Allowing Congress to create inferior federal courts

Granting federal law supremacy over state laws through the Supremacy Clause

These measures strengthened the national government but preserved important roles for state legal systems, reflecting the spirit of federation.

Compromise as a Mechanism for Unity

Negotiation at Philadelphia extended across issues too numerous for detailed examination here, but all reflected the central reality: the Constitution was built on compromise. Delegates repeatedly balanced ideology, state interests, and political practicality, shaping a new governmental framework through iterative discussion.

Major patterns in their negotiation included:

Balancing sectional interests between northern and southern states

Blending federal and state sovereignty through federalism

Ensuring popular and institutional checks within the new system

Retaining flexibility to adapt to future challenges

The Final Document

After months of debate, drafting, and revision, the delegates voted on September 17, 1787, to approve the proposed Constitution. Although several delegates refused to sign, the majority agreed that the document embodied the best achievable balance of principles and pragmatism. The Constitution’s creation marked a profound shift from the Articles of Confederation to a stronger, more dynamic central government, achieved entirely through negotiation and compromise among the states’ representatives.

FAQ

Debates were conducted under strict rules designed to promote open discussion without external pressure. All proceedings were kept secret, and delegates were prohibited from disclosing debates outside the chamber.

This secrecy encouraged candid negotiation, allowing delegates to propose, revise, and abandon ideas freely.

Key procedural features included:

Each state delegation receiving one vote

Delegates allowed to revisit and amend earlier decisions

George Washington presiding to maintain order and neutrality

Delegates arrived with growing consensus that the Articles created a government too weak to handle national issues such as taxation, interstate conflict, and economic instability.

Experiences under the Articles—including trade barriers between states, foreign policy weakness, and unrest like Shays’ Rebellion—convinced many that piecemeal amendments would not suffice.

This predisposed the convention towards creating an entirely new constitutional framework.

Delegates often negotiated in blocs reflecting shared regional concerns.

Northern interests commonly centred on commerce and stronger federal regulation.

Southern delegates prioritised agricultural economies, local autonomy, and protection for state-level control.

These blocs influenced:

Representation debates

Executive election methods

Allocation of federal powers

Informal gatherings outside the official chamber were crucial for building trust and brokering deals.

Delegates frequently met in taverns, boarding houses, and private lodgings to clarify misunderstandings and test alternative proposals.

These private networks helped soften rigid positions and prepared the ground for formal agreements inside the convention.

Dissenting delegates believed the final document granted too much power to the central government and lacked sufficient protections for individual rights.

Concerns included:

Absence of a bill of rights

Broad executive authority

Fear that states would lose sovereignty

These objections foreshadowed later Anti-Federalist arguments during the ratification debates.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the Great Compromise resolved a major dispute at the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

Mark Scheme

1 mark for identifying the dispute (e.g., disagreement between large and small states over representation).

1 mark for describing the solution (e.g., creation of a bicameral legislature).

1 mark for accurately explaining how the compromise balanced competing interests (e.g., proportional representation in the House and equal representation in the Senate).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which negotiation among delegates at the Philadelphia Convention shaped the structure of the new federal government.

Mark Scheme

1 mark for a clear opening statement addressing the extent of negotiation (e.g., “Negotiation was central to forming the new structure”).

1–2 marks for discussing specific compromises (e.g., Great Compromise, Electoral College, creation of the judiciary).

1–2 marks for explaining how these compromises shaped governmental structure (e.g., balancing state and national power, preventing dominance by any one group or region).

1 mark for a developed evaluative judgement (e.g., weighing negotiation against other influences such as pre-existing political theory or shared republican ideals).