AP Syllabus focus:

‘Federalists secured ratification by promising a Bill of Rights that listed individual liberties and explicitly restricted the powers of the federal government.’

The ratification of the Constitution sparked intense national debate, ultimately resolved when Federalists promised a Bill of Rights to safeguard liberties and limit federal authority, securing support.

The Road to Ratification

Efforts to ratify the newly drafted Constitution in 1787 confronted deep divisions among Americans. Federalists, who supported the document, argued that a stronger national government was essential for stability, economic development, and effective diplomacy. Their opponents, the Anti-Federalists, feared centralized power and warned that the proposed Constitution lacked sufficient protections for individual rights and for the sovereignty of the states. This conflict made ratification uncertain in several key states whose approval was necessary to ensure widespread legitimacy.

Federalist Arguments and Strategic Communication

The Federalists organized a coordinated campaign to defend the Constitution. They emphasized that the document created a limited government, constrained by checks and balances and separation of powers, which would prevent tyranny. Their most influential defense appeared in the Federalist Papers, a series of essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay.

Federalist Papers: A collection of 85 essays published between 1787 and 1788 advocating for the ratification of the Constitution and explaining its foundational principles.

Although persuasive, Federalist arguments alone could not overcome widespread public concern that the Constitution omitted explicit protections for fundamental rights such as freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and protections for the accused.

Anti-Federalist Opposition

Anti-Federalists maintained that without a clear statement of liberties, the new federal government could threaten the very freedoms Americans had fought to secure during the Revolution. They preferred revising the Articles of Confederation or adopting a new constitution only if it included a bill of rights from the start. Their position drew strong support among rural populations, small farmers, and individuals wary of distant authority.

Key Concerns Raised by Anti-Federalists

Anti-Federalists highlighted several vulnerabilities they perceived in the proposed Constitution:

Lack of explicit rights protecting personal freedoms

Fear of consolidated power in the executive and national government

Insufficient representation, particularly for small farmers and local communities

Absence of term limits, which they believed might enable entrenched political elites

Potential erosion of state sovereignty, raising concerns about federal dominance

These critiques created formidable obstacles for ratification in states such as Virginia, New York, and Massachusetts, each possessing large populations and considerable political influence.

The Promise of a Bill of Rights

Recognizing that opposition could derail the entire ratification project, leading Federalists committed to adding a Bill of Rights after ratification. This strategy became the pivotal move that turned the tide. By promising amendments that would specify individual liberties and restrict federal power, Federalists reassured skeptical voters and delegates that the new government would remain accountable and limited.

Bill of Rights: The first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution, guaranteeing individual liberties and restricting the powers of the federal government.

The promise of a Bill of Rights shaped several state ratifying conventions, where delegates voted to approve the Constitution while simultaneously proposing lists of recommended amendments. These proposals, though varied, consistently emphasized freedoms such as speech, assembly, religion, and due process.

After ratification, James Madison took primary responsibility for drafting the amendments. Although initially skeptical about the necessity of a bill of rights, Madison came to view it as an essential safeguard that would protect civil liberties and build public trust in the new government.

Ratification in the States

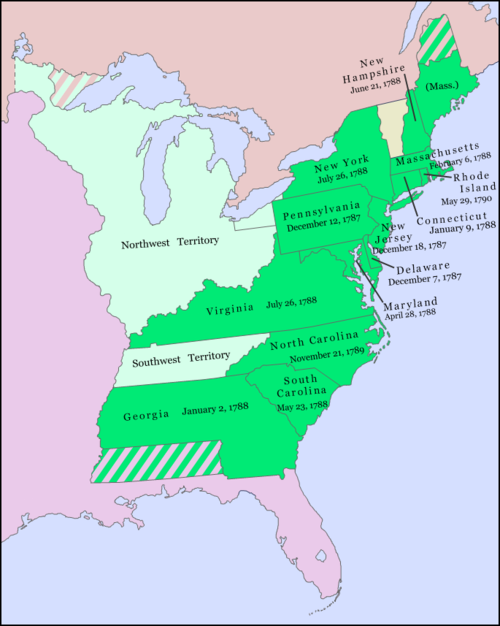

Ratification required approval from nine of the thirteen states, but Federalists sought broader consensus to avoid a fragmented union.

Map depicting the dates when each of the thirteen original states ratified the Constitution, illustrating the gradual spread of support. The shading highlights early adopters like Delaware and later ratifiers such as North Carolina and Rhode Island. The inclusion of only dates provides focused contextual detail aligned with the ratification sequence. Source.

Early successes in smaller states encouraged momentum, but several major states remained undecided. The promise of a Bill of Rights proved decisive in the following ways:

Massachusetts Compromise: Anti-Federalists agreed to ratify in exchange for recommended amendments.

Virginia and New York: Fierce debates ended with narrow votes in favor, heavily influenced by Federalist assurances of future rights protections.

North Carolina and Rhode Island: These states initially refused to ratify but joined after the new government advanced the promised amendments.

By 1788, enough states had ratified to secure the Constitution’s adoption, though political pressure continued to push for rapid introduction of the amendments.

Implementation of the Bill of Rights

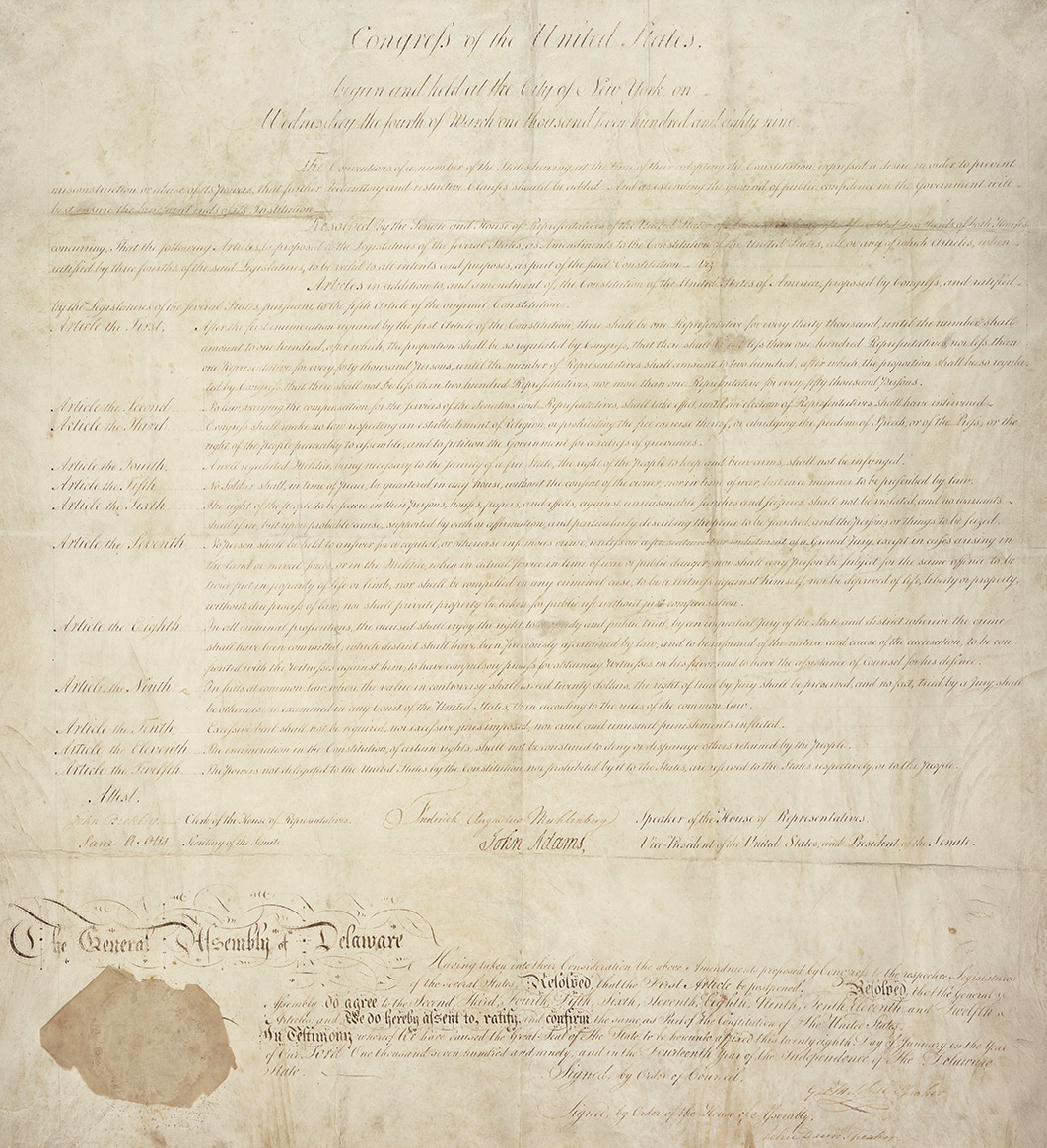

In 1791, the Bill of Rights was formally ratified, fulfilling the Federalists’ central promise.

Delaware’s parchment copy of the Bill of Rights with its certificate of ratification and state seal, illustrating how states formally approved the amendments. This document represents the tangible fulfillment of the Federalist promise that secured support for the Constitution. Additional signatures and formatting extend beyond syllabus requirements but enrich understanding of the ratification process. Source.

These amendments:

Protected freedoms such as speech, press, religion, and assembly

Ensured protections for the accused, including jury trials and safeguards against unreasonable searches

Affirmed that powers not delegated to the federal government remained with the states and the people

This development reassured Americans that the new federal system would not replicate the abuses of centralized power they associated with British rule.

Long-Term Significance

The ratification process and the creation of the Bill of Rights established foundational principles of American political culture. It demonstrated that constitutional design could be both adaptable and responsive to public concerns. The inclusion of the Bill of Rights strengthened support for the new federal system while embedding enduring protections that would shape American legal and political life for centuries.

FAQ

States with strong traditions of local autonomy, such as Virginia and Massachusetts, were more inclined to demand explicit rights protections before accepting a stronger national government.

In contrast, smaller states like Delaware and New Jersey, which feared being overshadowed by larger neighbours, were quicker to support the Constitution without insisting on extensive amendments.

These differing political cultures shaped whether the promise of a Bill of Rights became a decisive factor in gaining ratification.

Madison initially believed that structural safeguards in the Constitution were sufficient to prevent tyranny, but political reality shifted his view.

He recognised that Anti-Federalist scepticism threatened the new government's legitimacy and that amendments would unify factions.

Madison also saw an opportunity to control the amendment process himself, ensuring the additions strengthened—not weakened—the new national framework.

State conventions submitted long lists of recommended amendments, many of which influenced the final text.

Common proposals included:

Freedom of religion

Rights of the press and assembly

Protections against standing armies in peacetime

Limits on taxation powers

Jury trial guarantees

These suggestions created a broad template that Madison refined into the eventual Bill of Rights.

Anti-Federalists used widely circulated pamphlets and newspaper essays to warn readers that the new Constitution lacked protections against government overreach.

Their messaging gained particular traction in rural communities, where fears of distant authority were strongest.

This pressure helped force Federalists to adopt the promise of a Bill of Rights as a political concession necessary for ratification.

Congress received hundreds of amendment proposals from states, creating a need to consolidate overlapping or contradictory suggestions.

Key challenges included:

Selecting amendments that had broad support

Ensuring the list did not limit unenumerated rights

Maintaining coherence with the existing structure of the Constitution

Madison streamlined the proposals into twelve amendments, ten of which were ultimately ratified.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which Federalists attempted to secure ratification of the Constitution in 1787–1788.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark: Identifies a valid Federalist strategy (for example, promising a Bill of Rights, publishing the Federalist Papers).

• 2 marks: Provides a brief explanation showing how the strategy helped promote ratification.

• 3 marks: Provides a developed explanation explicitly linking the strategy to overcoming Anti-Federalist concerns or influencing key state conventions.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate the extent to which the promise of a Bill of Rights was the decisive factor in securing the Constitution’s ratification.

Mark scheme

• 1–2 marks: Provides general statements about ratification or Federalist and Anti-Federalist positions with limited relevance to the Bill of Rights.

• 3–4 marks: Explains the role of the Bill of Rights promise and offers at least one additional factor (such as Federalist communication, political pressures, or state-by-state debates).

• 5–6 marks: Provides a balanced, well-supported evaluation that assesses the relative importance of the promise of a Bill of Rights compared with other influences, making clear judgements about its significance across multiple states.