AP Syllabus focus:

‘Ratification debates pitted Anti-Federalists against Federalists, whose ideas were expressed in the Federalist Papers, especially by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison.’

Debates over the Constitution’s ratification revealed contrasting visions for American governance, as Federalists and Anti-Federalists contested national authority, individual rights, and the future shape of the new republic.

The Landscape of Ratification Debates

The struggle between Federalists and Anti-Federalists emerged in 1787–1788 after delegates at the Constitutional Convention proposed replacing the Articles of Confederation with a stronger national framework. The Constitution required approval from specially elected state conventions, making public persuasion central to the ratification process. This environment fostered vigorous political dialogue about the nature of republican government, the scope of federal authority, and the protection of personal liberties. Although both sides claimed to defend the ideals of the American Revolution, they differed fundamentally over how to secure liberty and ensure stable governance.

Federalist Arguments and Political Philosophy

Federalists advocated ratification and emphasized the necessity of a more effective central government capable of addressing national challenges such as interstate conflict, trade instability, and diplomatic weakness. They argued that the Articles had created a confederation too weak to preserve the union.

The Federalist Papers

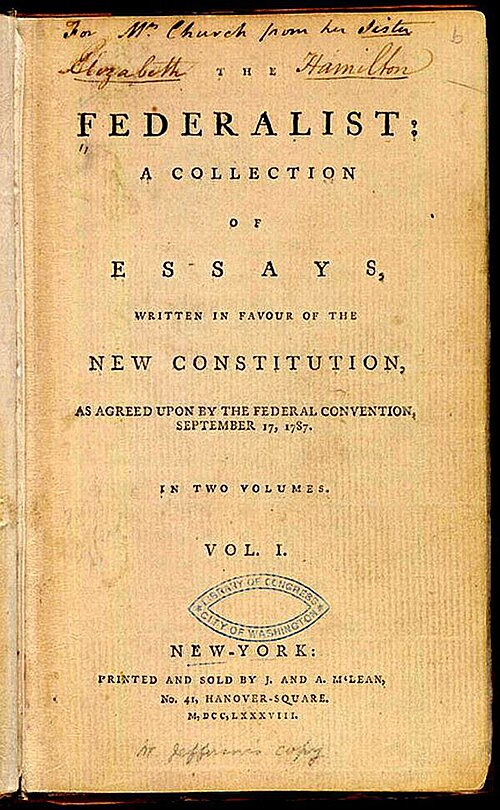

To strengthen public support, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay wrote the Federalist Papers, a collection of essays explaining and defending the new Constitution.

Title page of the 1788 first edition of The Federalist, the essay collection written under the pseudonym Publius by Hamilton, Madison, and Jay. The volume explained the principles of the Constitution and defended stronger national authority. The image includes historical typography but no additional content beyond the original title information. Source.

Federalist Papers: A series of 85 essays arguing for the Constitution’s ratification by explaining its principles and addressing criticisms of centralized authority.

The essays clarified key constitutional mechanisms such as checks and balances, separation of powers, and federalism. They asserted that liberty would be best protected not by weak government but by a system in which ambition would counteract ambition.

One of the most influential essays, Federalist No. 10, written by Madison, argued that a large republic would dilute the power of factions, preventing any single group from dominating government. Federalist No. 51 further explained how divided powers and institutional checks would prevent tyranny.

Core Federalist Claims

Federalists stressed several interconnected themes:

Need for national unity to prevent foreign interference and domestic disorder.

Balanced government structure capable of controlling abuses of power.

Representation that filtered public opinion through elected officials, promoting stability over sudden shifts in popular sentiment.

Economic coordination through federal regulation of commerce and taxation.

Federalists insisted that the Constitution preserved state authority through federalism while still empowering the national government to operate effectively across the continent.

Anti-Federalist Concerns and Visions of Liberty

Anti-Federalists opposed ratification because they feared the concentration of political power and the potential erosion of individual freedoms. Many had recently fought Britain’s centralized imperial authority and worried that the new federal government resembled the very system Americans had resisted.

Diverse but Connected Objections

Anti-Federalist viewpoints were diverse, but several common themes emerged:

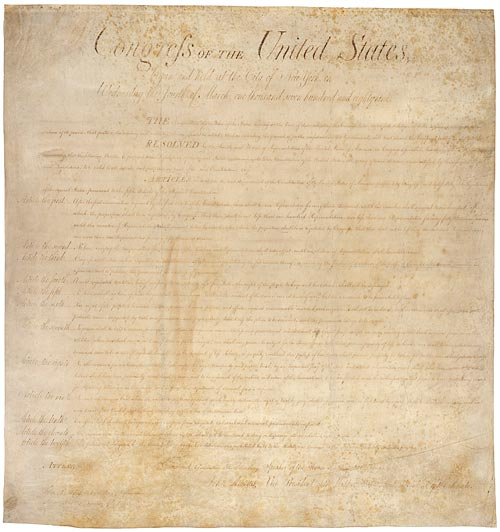

The Constitution lacked a Bill of Rights, leaving fundamental liberties unprotected.

The proposed national government could become distant from the people, weakening local control.

Broad federal powers over taxation, the military, and commerce threatened state sovereignty.

The executive branch, particularly the presidency, appeared dangerously monarchical.

Large republics were prone to corruption because citizens could not adequately oversee distant representatives.

These critiques echoed long-standing colonial traditions of self-rule and suspicion of centralized authority.

Leading Anti-Federalist Voices

Influential Anti-Federalists included Patrick Henry, George Mason, and Mercy Otis Warren, each of whom warned that the Constitution endangered the hard-won principles of the Revolution. They emphasized that republican government worked best in small, closely connected communities where civic participation was strongest.

Republicanism: A political philosophy emphasizing government by elected representatives, civic virtue, and the protection of natural rights.

Although Anti-Federalists lacked a coordinated publication like the Federalist Papers, they produced numerous pamphlets and essays—often under pseudonyms—that shaped public debates in state conventions.

Normal civic engagement remained vibrant throughout these exchanges, reinforcing expectations that the nation’s political system should be grounded in public consent.

Ratification, Compromise, and the Bill of Rights

The Constitution was ultimately ratified in 1788, but the debates revealed widespread concern about safeguarding individual freedoms. To secure support from hesitant states, Federalists promised to add a Bill of Rights, addressing the Anti-Federalists’ most powerful objection.

Engrossed copy of the U.S. Bill of Rights, created in response to Anti-Federalist concerns about centralized authority. It outlines protections for speech, religion, due process, and other liberties absent from the original Constitution. The document also includes two proposed amendments not immediately ratified, slightly exceeding the specific content of this subtopic. Source.

The Impact of the Ratification Debates

This ideological confrontation transformed American political culture by establishing patterns of organized debate, public persuasion, and constitutional interpretation. The exchange also reflected early struggles over how to balance liberty and order, a tension that would continue shaping national governance.

The debates strengthened expectations for written protections of rights.

They demonstrated the importance of compromise in American political development.

They provided key constitutional interpretations through prominent Federalist essays.

They elevated the principle that governmental power must remain accountable to the people.

State ratifying conventions became the main arenas where Federalists and Anti-Federalists clashed over whether to accept the new Constitution drafted in Philadelphia in 1787.

Howard Chandler Christy’s painting depicts the 1787 signing of the Constitution in Independence Hall. Leaders such as Washington, Franklin, Hamilton, and Madison appear prominently, visually linking the drafting process to the later Federalist–Anti-Federalist debates. Although it illustrates the signing rather than the ratification struggle, it anchors the document at the center of the controversy. Source.

The ratification debates between Federalists and Anti-Federalists thus became a foundational moment in defining American constitutionalism and political identity.

FAQ

Support often reflected local economic interests. Commercial centres in the North, dependent on trade regulation and stable currency, tended to favour the stronger national government advocated by Federalists.

Rural and backcountry regions, particularly in the South and West, were more suspicious of centralised authority and leaned toward Anti-Federalist critiques.

Local political culture also mattered: states with strong traditions of legislative dominance, such as Virginia, produced influential Anti-Federalist voices.

Confusion stemmed from the Constitution’s novelty. It created a federal system that was neither a pure confederation nor a centralised state, forcing voters to interpret an unfamiliar political arrangement.

Citizens also had limited access to the full text. Newspapers often printed excerpts or summaries, allowing Federalists and Anti-Federalists to frame its meaning selectively.

Many Americans associated power concentration with British tyranny, so judging whether the new system avoided this risk required weighing abstract principles rather than existing precedents.

Some Anti-Federalists suggested revising the Articles of Confederation rather than abandoning them altogether. Their alternatives typically included:

Maintaining stronger state sovereignty

Granting Congress limited authority to raise revenue or regulate trade

Adding explicit protections for individual liberties

A minority supported calling a second constitutional convention to draft a more decentralised plan. However, Anti-Federalist proposals lacked the unified structure and persuasive coordination of the Federalist Papers.

Federalists coordinated their messaging more effectively, using a consistent pseudonym—Publius—and circulating their essays widely across state newspapers.

Anti-Federalists wrote under a variety of pseudonyms, including Brutus, Centinel, and Federal Farmer. This diversity reflected a broader coalition but made their arguments less uniform.

Federalists also had advantages in urban printing networks, giving their essays quicker and wider distribution, especially in states where ratification was uncertain.

The Constitution bypassed state legislatures and relied on elected conventions, forcing candidates to campaign directly on their stance toward the new framework.

This design reduced legislative biases and placed decision-making in temporary bodies focused solely on ratification.

Conventions allowed for extended public debate, amendment proposals, and negotiations. In closely divided states like Massachusetts and Virginia, convention compromises—such as recommending a Bill of Rights—were decisive in securing narrow Federalist victories.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why Anti-Federalists opposed the ratification of the United States Constitution in 1787–1788.

(1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks for a clear and accurate explanation of one reason for Anti-Federalist opposition.

1 mark: Identifies a valid Anti-Federalist concern (e.g., lack of a Bill of Rights, fear of centralised power).

2 marks: Provides a brief explanation showing why this concern led to opposition.

3 marks: Offers a developed explanation showing clear understanding of Anti-Federalist political principles and how they related to the Constitution’s proposed structures.

Indicative content:

Concerns about the absence of explicit protections for individual rights; belief that a strong national government threatened state sovereignty; fear that the presidency resembled monarchical authority; worry that representatives in a large republic would be too distant from the people.

(4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of the ratification debates, evaluate the extent to which the Federalist Papers were effective in shaping public opinion in favour of the Constitution

(4–6 marks)

Award up to 6 marks for an evaluation of the effectiveness of the Federalist Papers in shaping support for ratification.

1–2 marks: Demonstrates general knowledge of the Federalist Papers or the ratification debates but with limited detail or analysis.

3–4 marks: Provides accurate explanation of the role and arguments of the Federalist Papers, with some assessment of effectiveness.

5–6 marks: Offers a well-developed evaluation with specific references to Federalist arguments (such as those in Federalist Nos. 10 and 51), balanced analysis of their impact, and recognition of contextual factors (e.g., state-by-state debates, Anti-Federalist responses).

Indicative content:

Arguments that a large republic would control factions; explanations of checks and balances; reassurance that liberty would be protected under the new system; widespread printing and distribution of the essays; limitations, such as uneven readership and the continuing influence of Anti-Federalist criticisms; ultimate contribution to securing ratification in key states.