AP Syllabus focus:

‘Use evidence from Period 4 to evaluate how expanding democracy, political parties, and federal power debates shaped American identity from 1800 to 1848.’

Between 1800 and 1848, expanding democratic participation, intensifying party competition, and debates over federal authority reshaped Americans’ political expectations, contributing to a distinct national identity grounded in civic involvement and ideological conflict.

Expanding Democracy and Emerging Political Identity

The early nineteenth century witnessed major shifts in political participation that redefined Americans’ sense of themselves as citizens. States steadily eliminated property qualifications for voting, broadening access to political life for adult White men and creating new expectations of popular sovereignty—the principle that legitimate authority derives from the people.

Election Day in Philadelphia (1815) shows a bustling crowd gathered around public buildings on voting day, highlighting how elections became major civic occasions. The mix of social interaction, political activity, and visible symbols of government illustrates how participation in elections reinforced a shared sense of national belonging. The painting includes additional social details—such as street vendors and bystanders—that go beyond the syllabus but help contextualize voting as part of everyday urban life. Source.

Popular sovereignty: The belief that political authority originates from the collective will of the people, expressed through participation in elections and civic processes.

As suffrage expanded, Americans increasingly conceptualized citizenship as tied to active political engagement, not merely social status or economic independence. This shift encouraged widespread interest in elections, campaigns, and public policy. Politicians responded by developing strategies to appeal to ordinary voters, reinforcing the idea that the public itself was central to shaping the nation’s direction. The transformation of voting into a mass activity promoted a shared national culture in which political participation became a defining element of American identity.

Key Processes in Democratic Expansion

Removal of most property-based voting requirements for White men

Growing emphasis on direct campaigning and candidate outreach

Increased use of political rallies, newspapers, and partisan messaging

Enhanced expectations that all White male citizens deserved a voice in government

These developments strengthened the connection between individual political involvement and national belonging, though they also highlighted enduring exclusions.

Political Parties and the Formation of National Identity

The rise of mass political parties profoundly influenced how Americans understood themselves and their nation. After 1800, competition between evolving party coalitions—first Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, then Democrats and Whigs—encouraged Americans to identify with partisan visions of national purpose.

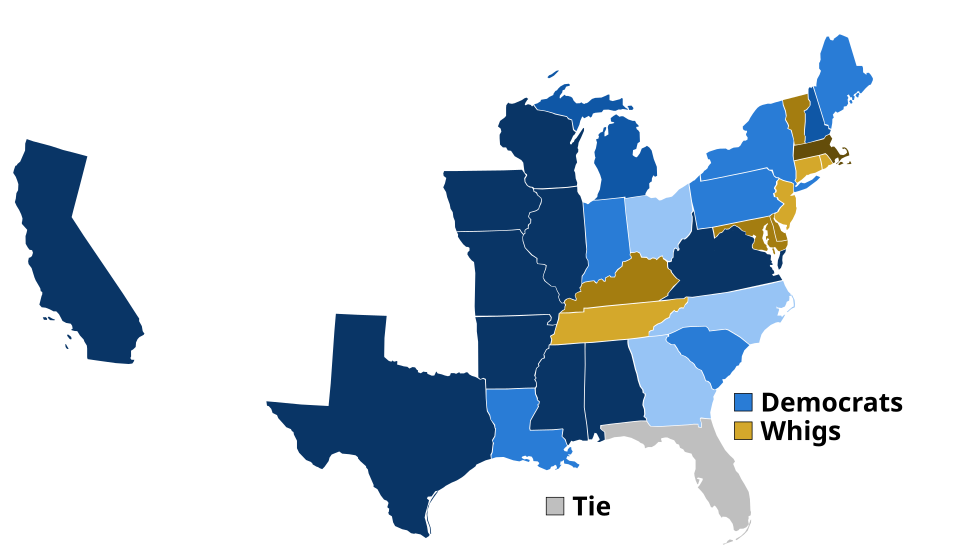

This map summarizes U.S. presidential election outcomes from 1828 to 1852, shading states according to whether they usually supported Democrats or National Republican/Whig candidates. It highlights how the Second Party System turned national elections into truly national contests, reinforcing partisan identities across multiple regions. The map includes data through 1852, slightly beyond the 1800–1848 focus, but the patterns visible for elections up to 1848 align directly with the syllabus’ emphasis on party competition and participatory democracy. Source.

Parties as Vehicles for Political Belonging

Political parties broadened participation by:

Coordinating national and state-level campaigns

Producing newspapers that shaped public debate

Mobilizing voters through meetings, parades, and organizations

Offering ideological frameworks for interpreting national issues

Through these mechanisms, parties provided the structure through which millions of Americans engaged with national politics. Partisan identity became a common feature of everyday life, shaping how citizens viewed government power, economic policy, and regional interests.

As parties recruited mass followings, they fostered a sense of national community grounded in political participation. Even divisive debates contributed to a shared political culture by normalizing disagreement and competition within the democratic process.

Federal Power, Constitutional Interpretation, and Identity

During Period 4, debates over the proper extent of federal authority became central to American political life. Supreme Court decisions, presidential policies, and legislative disputes all contributed to a broader national conversation about how the Constitution should guide governance.

Federal authority: The power exercised by the national government, particularly in areas such as commerce, taxation, judicial review, and interstate relations.

Supreme Court decisions under Chief Justice John Marshall—such as McCulloch v. Maryland and Gibbons v. Ogden—asserted federal supremacy and clarified constitutional interpretation. These rulings strengthened the legitimacy of national institutions, contributing to a shared American identity rooted in the stability of federal law. Yet they also fueled opposition from those who favored states’ rights, reinforcing ideological divides that shaped political affiliations and regional identities.

A sentence of normal text separates this from further content on political conflict without introducing another definition. Americans increasingly viewed their national belonging through the lens of these constitutional struggles, defining themselves as supporters or opponents of an energetic federal government.

Federal Power Debates as Drivers of Identity

Disputes over the national bank highlighted contrasting visions of economic governance

Tariff conflicts revealed tensions between regional interests and national policy

Arguments over internal improvements raised questions about constitutional limits

Political and judicial decisions shaped public expectations for federal leadership

These conflicts anchored national discourse, making constitutional interpretation a key marker of political identity.

Participatory Democracy and the Shaping of American Ideals

The growing emphasis on political participation encouraged Americans to associate national identity with civic engagement and ideological commitment. Voting, debating, and joining political organizations became expressions of belonging in the republic. As newspapers expanded and literacy increased, more Americans followed national events, reinforcing a shared political consciousness.

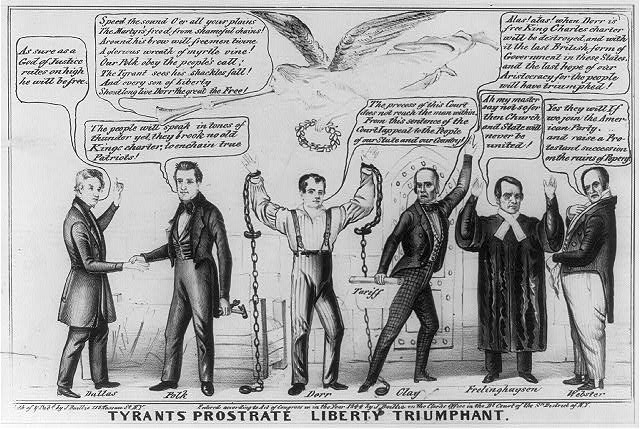

This mid-19th-century cartoon, titled “Tyrants prostrate liberty triumphant,” depicts Thomas Dorr and his supporters breaking political chains and appealing to “the people” against an old royal charter. The imagery dramatizes conflicts over suffrage and constitutional authority, embodying the era’s belief that legitimate power should flow from broad popular consent. The cartoon includes additional figures and slogans tied specifically to the Dorr Rebellion and 1840s party politics, which go beyond the syllabus but still reinforce themes of expanding democracy and contested authority. Source.

The Cultural Meaning of Citizenship

Citizenship became linked to the right and duty to participate

Partisan involvement shaped social networks and community identity

Democratic rhetoric celebrated equality among White men while excluding others

National ideals increasingly drew from the principles of popular involvement

Even as the era’s democratic expansion excluded women, Indigenous peoples, and African Americans, it laid foundations for future reform movements. The belief that ordinary people shaped the republic became central to how Americans understood their nation during Period 4.

FAQ

Expanding participation made politics more visible in daily life. Citizens increasingly attended rallies, read partisan newspapers, and discussed political issues in public spaces.

This shift helped normalise political engagement as a common social activity rather than an elite privilege.

As political events became communal gatherings, participation reinforced shared expectations of involvement in shaping the nation’s future.

State legislatures framed suffrage reforms around ideals of White male equality, associating political participation with racial and gender hierarchy.

Many lawmakers believed that political rights required independence, a standard they applied selectively to privilege White men.

Black Americans, women, and Indigenous peoples were explicitly excluded in many states to maintain existing power structures and social order.

Partisan newspapers provided voters with accessible political narratives, speeches, and editorials that connected local concerns to national debates.

They also fostered emotional attachment to parties by presenting political issues through a shared ideological lens.

Because newspapers circulated widely across regions, they contributed to a more unified political culture grounded in common sources of information.

These events offered ordinary citizens a space to express political preferences publicly, reinforcing the idea that government responded to popular will.

Activities such as listening to speeches, chanting slogans, and marching in parades helped participants see themselves as active contributors to national life.

This public participation nurtured a sense of ownership over political outcomes and affirmed democratic identity.

Debates over tariffs, internal improvements, and federal institutions prompted different regions to articulate distinct visions of the nation’s future.

For example:

Northerners often favoured strong federal authority to support commerce and infrastructure.

Southerners tended to defend states’ rights to protect slavery and agricultural interests.

These contrasts sharpened regional political cultures while simultaneously embedding conflict as a central feature of American national identity.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which the expansion of political participation between 1800 and 1848 contributed to the formation of a distinct American national identity.

Mark scheme (3 marks total)

1 mark for identifying a valid development, such as the removal of property requirements for voting or the rise of mass electoral participation.

1 mark for explaining how this development broadened citizens’ involvement in public life.

1 mark for linking this change to the creation of a shared national political identity grounded in democratic participation.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using evidence from the period 1800–1848, evaluate how debates over federal authority shaped American political identity. In your response, consider the role of political parties and constitutional interpretation.

Mark scheme (6 marks total)

1 mark for identifying relevant federal authority debates (e.g., the national bank, tariffs, internal improvements).

1 mark for describing the constitutional basis of these debates, such as differing interpretations of federal versus state power.

1 mark for explaining how political parties used these issues to define their ideological positions.

1 mark for providing specific historical evidence (e.g., Supreme Court decisions like McCulloch v. Maryland or Gibbons v. Ogden).

1 mark for analysing how these debates contributed to competing visions of national identity.

1 mark for making a clear evaluative judgement showing how these conflicts helped shape broader political identity in the early republic.