AP Syllabus focus:

‘Use evidence to explain how innovations in technology, agriculture, commerce, and transportation reshaped society and contributed to national and regional identities.’

The market revolution dramatically transformed the United States between 1800 and 1848, reshaping work, mobility, and regional identities as technological, agricultural, commercial, and transportation innovations redefined economic life.

Transformative Economic Change in the Early Nineteenth Century

Economic transformation in this period stemmed from interconnected developments that shifted the United States from a semi-subsistence economy to a more commercial and industrial one. These forces altered how Americans understood community, opportunity, and national belonging.

Transportation Innovations and a Connected National Economy

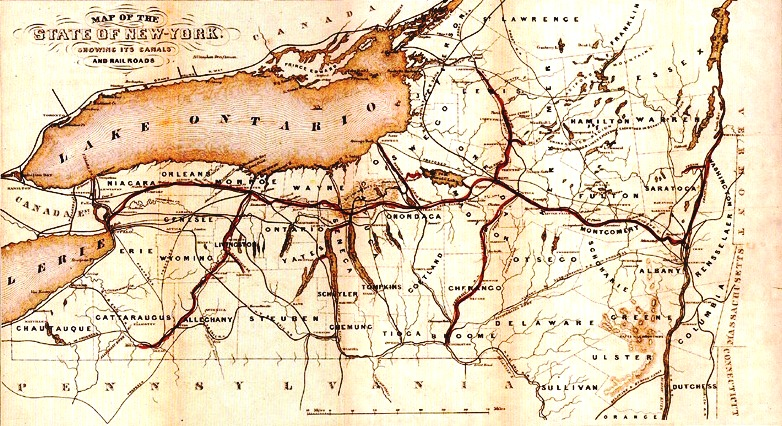

Transportation breakthroughs were among the most visible catalysts of the market revolution. New systems fundamentally changed the pace and scale of movement across the nation.

Turnpikes improved overland routes for freight and travelers.

Canals, especially the Erie Canal, linked western agricultural areas to eastern cities.

Steamboats enabled two-way river commerce, overcoming upstream barriers.

Railroads later accelerated national integration and allowed rapid shipment of goods and people.

Transportation Revolution: A period of rapid development in roads, canals, steamboats, and railroads that connected regional markets and stimulated economic growth.

These networks strengthened ties between regions, encouraged western migration, and stimulated interregional trade, promoting the idea of a dynamic, opportunity-rich American identity.

This 1834 map highlights the expanding web of canals and railroads that linked eastern cities, interior markets, and western farms into a more unified national economy. Students can trace routes such as the Erie Canal and early rail lines to see how infrastructure supported regional specialization and a shared sense of American progress. The map includes additional route profiles and technical details beyond syllabus requirements, which can be ignored while focusing on broader regional connections. Source.

Improved connectivity also fostered regional specialization, a process in which areas concentrated on the goods they produced most efficiently.

Technological and Industrial Innovation

Expanding transportation capacity was matched by innovations in manufacturing and mechanization. Interchangeable parts, popularized by Eli Whitney, standardized production and encouraged factory growth. Textile machinery, adopted from British models, launched early industrialization in the Northeast.

Water-powered spinning and weaving machinery made cloth production faster and less labor-intensive.

Machine tools increased productivity in metalworking and other trades.

The telegraph improved commercial communication, enabling markets to coordinate supply, pricing, and transportation more efficiently.

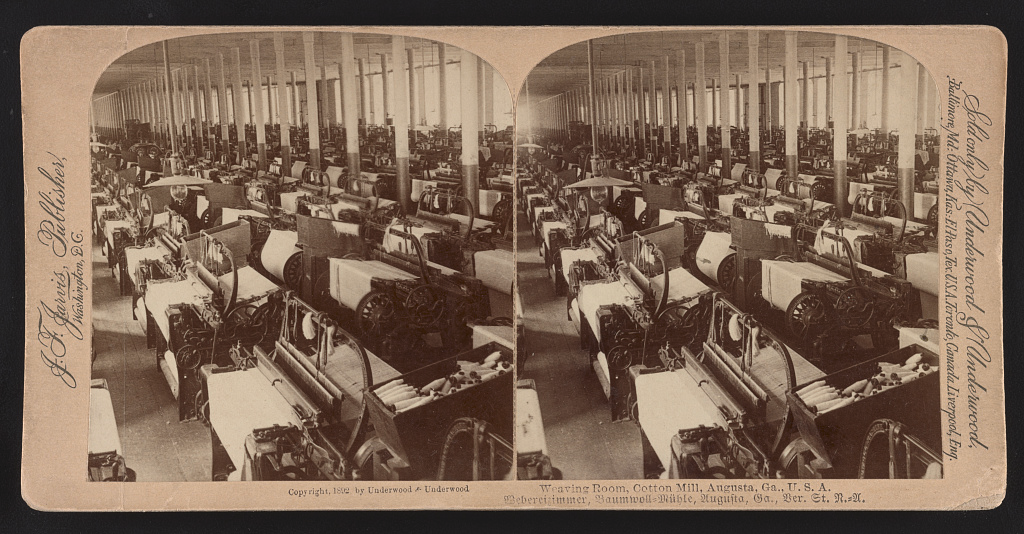

These technologies helped shift many Americans from home-based or artisanal production to wage labor in centralized factories.

This stereograph of a weaving room shows rows of power-driven looms and the regimented workspace associated with factory production. Although the photograph dates from 1892, it reflects industrial processes rooted in the early market revolution that helped redefine Americans as wage-earning workers. The image includes later industrial details and its Georgia location, which exceed syllabus needs but still effectively illustrate the factory environment. Source.

Agricultural Transformation and Regional Economic Patterns

Agricultural change was equally important to the market revolution. New tools and farming techniques increased productivity while shaping distinct regional identities.

In the Midwest, innovations such as the steel plow and mechanical reaper expanded wheat and grain farming.

In the South, the profitability of cotton soared after the invention of the cotton gin, and cotton became deeply embedded in regional identity and political culture.

Improved transportation linked farmers to distant markets, encouraging commercial rather than subsistence agriculture.

Commercial Agriculture: A system of farming oriented toward selling crops in national or international markets rather than producing primarily for local or household use.

These developments contributed to contrasting economic systems: industrial capitalism in the North, plantation slavery in the South, and mixed agriculture in the West. Each region increasingly defined itself—economically and culturally—around its dominant productive activities.

Commerce, Capital, and Expanding Markets

The market revolution broadened the reach and scale of American commerce. Banks and investment networks multiplied, channeling capital into infrastructure, industry, and land development. Expanding markets reshaped identity by fostering:

A belief in economic individualism, emphasizing personal ambition and mobility.

Confidence in national economic potential, contributing to early expressions of American exceptionalism.

More frequent interaction among regions, which promoted shared commercial expectations even as values diverged.

Merchants, manufacturers, and farmers increasingly operated within a national market system, reinforcing the idea that Americans were economically interconnected despite political or cultural differences.

Social Change and Shifting Identities in a Market Society

Economic change affected social structure and daily life, altering how Americans understood their place in society.

A middle class grew around salaried work, education, and consumer culture.

A working class expanded in factories, where wage labor transformed household dynamics.

Greater economic inequality sharpened social distinctions, influencing reform movements and political participation.

The emerging middle class identified with values such as self-discipline, punctuality, and upward mobility—traits they believed defined the American character. Meanwhile, the experiences of wage workers, artisans, small farmers, and enslaved laborers contributed to different, often competing, interpretations of American opportunity and identity.

Regional Identities and National Tensions

The market revolution heightened regional differentiation even as it linked the country more closely. The North celebrated industrial innovation and free labor ideology; the South championed cotton production and slavery; the Midwest promoted commercial agriculture and internal improvements. These regional identities shaped political alliances, cultural values, and understandings of national destiny.

Federal debates over tariffs, banks, and internal improvements reflected these competing identities, revealing how economic change generated both shared national pride and deep sectional tension.

Economic Change as a Force in National Identity

Together, technological, agricultural, commercial, and transportation innovations contributed powerfully to American identity between 1800 and 1848. The United States increasingly saw itself as a modernizing nation defined by mobility, entrepreneurship, and economic opportunity, even as regional specialization and inequality created divergent visions of what it meant to be American.

This mid-19th-century map traces the route of the Erie Canal, showing how it linked inland farms and towns to Atlantic markets. Students can follow the line from Buffalo to Albany to understand how one major internal improvement supported western migration, commercial agriculture, and New York’s rise as a commercial center. The map includes extra geographic detail not required by the syllabus, which can be overlooked in favor of the canal’s overall economic importance. Source.

FAQ

The Market Revolution encouraged the belief that individuals could shape their economic futures through mobility, enterprise, and wage work, rather than relying on inherited land or family-based production.

This was reinforced by expanding access to credit, new occupations in transport and manufacturing, and the spread of commercial markets that rewarded initiative.

Many Americans began to equate opportunity with participation in a national marketplace, strengthening a shared cultural emphasis on ambition and self-improvement.

Internal improvements raised questions about whether the federal government should promote a national economic vision or allow states and regions to develop independently.

Debates centred on:

Federal funding for roads and canals

Constitutional limits on national power

Concern that certain regions would benefit disproportionately

Supporters argued that infrastructure fostered unity and national progress, while critics feared overreach and regional imbalance.

Many artisans struggled as factory production undercut prices and standardised goods, reducing demand for individually crafted items.

Some adapted by specialising in high-quality or bespoke work, while others shifted into managerial roles, wage labour, or retail trades.

These changes contributed to new distinctions between skilled and unskilled labour, altering social identities within urban centres.

The telegraph and expanding postal networks enabled rapid transmission of prices, news, and commercial information, linking distant regions more closely.

Farmers and merchants could adjust production and sales decisions based on wider market conditions, aligning their identities with national rather than purely local economic rhythms.

At the same time, shared news culture fostered perceptions of belonging to a common nation, even as regional economic differences persisted.

New transport routes and commercial farming opportunities encouraged thousands of families to move west, where they built communities centred on market exchange rather than isolated subsistence.

These western settlers identified strongly with mobility, land access, and integration into national markets.

Their expectations for federal support—such as surveys, land policy, and infrastructure—shaped a regional identity that valued both independence and connection to the wider national economy.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify and briefly explain one way in which technological or transportation innovations during the Market Revolution (1800–1848) contributed to the development of a distinct regional or national identity in the United States.

Mark scheme (3 marks total)

1 mark for correctly identifying a relevant innovation (e.g., steamboats, railroads, Erie Canal, interchangeable parts, telegraph).

1 mark for explaining its impact on economic or social change (e.g., improved connectivity, faster production, growth of factory labour).

1 mark for linking this change to the formation of a regional or national identity (e.g., North’s industrial identity, national sense of progress, expanding commercial ties).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of the period 1800–1848, evaluate the extent to which the Market Revolution reshaped American regional identities. In your answer, address developments in technology, agriculture, commerce, and transportation.

Mark scheme (6 marks total)

1 mark for a clear argument about the extent of change (e.g., “to a great extent,” “to a limited extent,” or a balanced judgement).

1–2 marks for accurate description of technological and industrial developments (e.g., textile machinery, interchangeable parts, mechanisation).

1–2 marks for explaining changes in agriculture or commerce that contributed to regional differentiation (e.g., cotton in the South, grain production in the Midwest, rise of northern factories).

1 mark for analysis connecting these developments to emerging regional identities (e.g., southern plantation identity, northern free-labour ideology, midwestern commercial farming identity).

1 mark for use of specific evidence and factual detail drawn from the period.