AP Syllabus focus:

‘Explain how expansion and regional economies intensified disputes over slavery in new territories, shaping competing American and regional identities.’

Growing territorial expansion and intensifying economic differences deepened disputes over slavery, fostering rival regional identities and reshaping how Americans understood political power, national belonging, and the future of the republic.

Sectional Tensions and the Meaning of Sectionalism

The early nineteenth century witnessed increasingly divergent regional priorities rooted in contrasting economic structures and social ideologies.

Sectionalism: Loyalty to the interests, identity, and political priorities of one’s region over those of the nation as a whole.

As westward expansion continued, sectional loyalty increasingly guided political behavior, shaping debates in Congress and influencing how Americans conceptualized the nation’s purpose and moral direction. Southern planters, Northern industrialists, and Western settlers each developed distinctive visions of economic development and social order.

Expansion, Slavery, and Competing Visions of the West

Territorial expansion repeatedly thrust the issue of slavery into national debates.

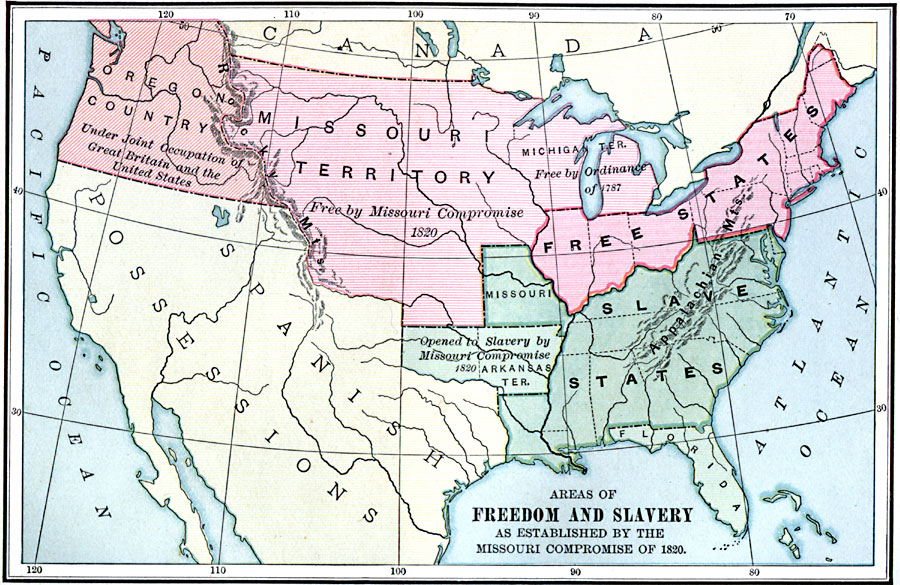

This map illustrates the areas of freedom and slavery in the United States in 1820 as defined by the Missouri Compromise, including the 36°30′ boundary limiting slavery’s expansion. By distinguishing free states, slave states, and territories, it highlights how decisions about western lands became central to sectional tensions. The image includes surrounding regions such as Spanish and British territories, which exceed syllabus requirements but aid geographic context. Source.

The West as a Battleground of Ideologies

Different groups imagined the West in competing ways:

Southern slaveholders believed that expanding plantation slavery into new lands was essential to preserve political balance and economic opportunity.

Northern free-labor advocates asserted that slavery’s expansion threatened opportunities for small farmers and violated the ideals of republican equality.

Western settlers often held mixed views, seeking both economic autonomy and political influence, while remaining sensitive to the balance of power between North and South.

These conflicting visions ensured that every new territory raised profound questions about democracy, labor, and the structure of the Union.

Economic Divergence and Identity Formation

Regional economies intensified debates over slavery by aligning economic interests with ideological identities.

Northern Industrial Growth

The market revolution accelerated manufacturing and urbanization in the North, strengthening a free-labor ideology that celebrated wage labor, social mobility, and industrial growth. Many Northerners came to view slavery as both economically backward and morally incompatible with national progress.

Southern Plantation Expansion

In contrast, the cotton economy bound the South tightly to enslaved labor. Plantation wealth, social hierarchy, and political influence were intertwined, reinforcing a regional identity that defended slavery as essential. Southern leaders increasingly articulated proslavery arguments that framed slavery as a positive good rather than a necessary evil, further sharpening sectional contrasts.

Western Economic Ambiguity

Western economies blended small-scale farming, emerging commerce, and mobility. While many Westerners opposed the political power of slaveholding elites, others saw potential economic advantage in aligning with Southern or Northern interests, producing a region whose identity was deeply contested.

Political Conflict and the Question of National Power

As expansion continued, disputes over slavery shaped fierce national political conflict.

Balancing Power in Congress

Debates over maintaining an equal number of free and slave states dominated political decision-making.

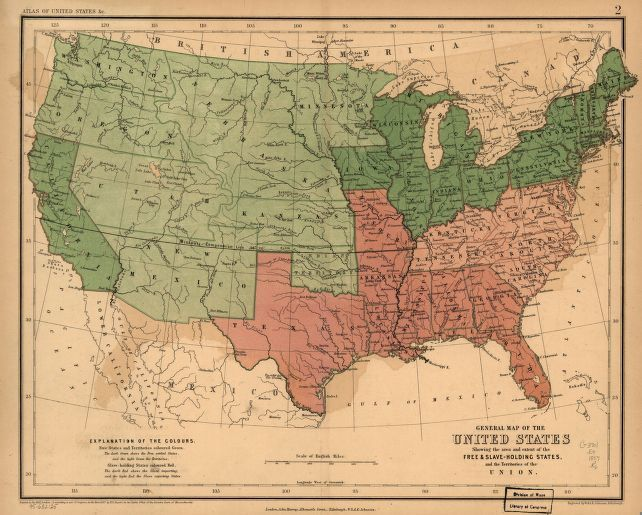

This map displays free states and territories in green and slaveholding regions in red, making clear the sectional divide that shaped political struggles over congressional balance. It visually reinforces how geographic blocs translated into political power and fostered mutual suspicion between regions. The map extends slightly beyond the 1848 scope but accurately reflects sectional patterns essential to the topic. Source.

Federal Versus State Authority

Disagreements about slavery often resurfaced as debates over constitutional interpretation. Southerners increasingly emphasized states’ rights as a means of protecting slavery, while many Northerners argued for broader federal power to regulate territories.

A normal sentence continues here to provide separation from the next definition.

States’ rights: The political principle asserting that individual states possess sovereign authority and may limit or resist federal actions they deem unconstitutional.

This ideological conflict magnified sectional identities, making political compromise more difficult.

Moral Debates and Cultural Identities

The slavery issue was not solely political or economic; it became a profound moral and cultural conflict.

Growing Northern Antislavery Sentiment

Though not universally abolitionist, many Northerners developed a regional identity that associated freedom, industry, and moral progress with the rejection of slavery’s expansion. Antislavery activism amplified cultural divisions by framing the South as morally and socially distinct from the rest of the nation.

Southern Cultural Defense of Slavery

Southern identity grew increasingly tied to a hierarchical social order. Influential Southern thinkers argued that slavery provided stability, upheld racial order, and preserved economic prosperity. These cultural justifications strengthened the perception that the South possessed a unique and endangered way of life.

Territorial Crises and the Escalation of Identities

Each territorial crisis deepened competing identities:

The Missouri debates revealed the explosive implications of expansion for national unity.

Conflicts over the Southwest raised fears about the long-term balance of free and slave states.

Continued westward migration ensured that slavery remained at the center of national politics.

Americans increasingly defined themselves not simply as citizens of a shared nation but as members of rival Northern, Southern, or Western communities whose futures seemed fundamentally incompatible. These sectional identities, shaped by the intertwined forces of expansion, economic divergence, and the institution of slavery, set the stage for the nation’s escalating sectional crisis.

FAQ

Political rhetoric increasingly portrayed regional interests as moral imperatives. Southern politicians framed slavery as essential to maintaining social order, while Northern leaders emphasised the virtues of free labour and economic modernisation.

Campaign speeches, newspaper editorials, and congressional debates often used emotive language that depicted the opposing region as a threat to national stability, reinforcing the sense that each section had distinct and incompatible identities.

As settlers moved westward, they carried regional values with them. Southerners often sought to expand plantation agriculture, while Northern migrants promoted free-labour farming.

These differing expectations shaped voting blocs in new territories and contributed to local political disputes, making the West a crucial arena where sectional competition played out.

Western leaders responded to rapidly changing local economic demands. Their political stances often reflected:

Desire for federal investment in infrastructure

Competition for population growth

Fear of domination by either Northern or Southern political coalitions

This flexibility allowed Western politicians to build alliances that best served local interests rather than rigid regional ideologies.

Newspapers increasingly catered to local audiences, publishing partisan commentary that highlighted perceived regional injustices.

Southern newspapers defended slavery as a social necessity, while Northern papers criticised its expansion as a threat to free labour and democratic fairness. This regionalised media landscape deepened perceptions that the nation was divided into distinct, competing societies.

Both major parties attempted to balance sectional factions. Party leaders often avoided explicit national positions on slavery, instead relying on local platforms to appease voters.

Compromise-based strategies—such as supporting neutral territorial legislation or dividing platforms by region—temporarily reduced open conflict but ultimately contributed to long-term instability as sections demanded clearer national commitments.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which territorial expansion contributed to the growth of sectional tensions in the United States between 1800 and 1848.

Mark scheme

1 mark: Identifies a valid way expansion heightened sectional tensions (e.g., disputes over whether slavery would expand into new territories).

2 marks: Provides a brief explanation showing how expansion intensified conflict (e.g., political battles over maintaining balance in Congress).

3 marks: Offers a clear, accurate explanation linking expansion to the emergence of competing regional identities or political crises (e.g., Missouri debates demonstrating stark differences between free and slave states).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which economic differences between the North and South shaped competing American identities in the period 1800–1848.

Mark scheme

1–2 marks: Gives basic statements about Northern and Southern economic differences with limited development.

3–4 marks: Explains how distinct economic systems (e.g., industrial North, slave-based plantation South) contributed to developing different regional priorities or attitudes.

5–6 marks: Provides a well-supported analysis showing how these economic differences became intertwined with ideological, political, or social identities, and explains the broader impact on sectional tensions or national unity.