AP Syllabus focus:

‘Evaluate how new national culture, religious revivals, and reform movements helped define American ideals while also exposing divisions.’

American culture and reform in Period 4 fostered powerful ideals of unity, moral uplift, and national identity while simultaneously exposing deep social, political, and sectional divisions.

Cultural Developments and National Identity

The early nineteenth century witnessed an expanding national culture, shaped by new literary expressions, artistic movements, and civic ideals that aimed to bind the republic together. Writers and artists promoted themes of national pride and democratic possibility, contributing to a shared vision of the United States’ purpose. This cultural flowering accompanied ongoing debates over who belonged within the expanding definition of “American,” revealing differences across gender, race, class, and region.

Romanticism and Beliefs in Human Potential

Transatlantic Romanticism, an intellectual movement emphasizing emotion, nature, and individual experience, profoundly influenced American thought. It generated optimism about human perfectibility and encouraged new cultural forms that resonated with democratic ideals. Romanticism also intersected with emergent philosophies such as Transcendentalism, which emphasized intuition, moral elevation, and the inherent goodness of people. These cultural movements strengthened commitments to liberty and self-improvement, even as their universal claims clashed with the lived realities of slavery and inequality.

Transcendentalism: A philosophical movement influenced by Romanticism that stressed individual intuition, moral self-reliance, and the pursuit of spiritual truth beyond empirical observation.

The rise of these movements celebrated cultural unity but also sharpened critiques of mainstream institutions, creating ideological conflict between reform-minded intellectuals and defenders of traditional social hierarchies.

Religious Revivals as Engines of Unity and Tension

The Second Great Awakening, a widespread Protestant revival, profoundly reshaped American religious life and contributed to national ideals rooted in democratic participation and individual moral choice. Revivalist gatherings attracted diverse communities and emphasized accessible salvation, suggesting that spiritual equality could mirror political equality.

Camp meetings and revivals brought thousands together in open-air gatherings that blended preaching, music, and emotional appeals, reinforcing shared evangelical values.

This hand-colored engraving depicts a Methodist camp meeting in the early 1800s, with crowds assembled outdoors to hear revival preaching. Such gatherings were central to the Second Great Awakening, spreading evangelical beliefs and creating a sense of religious community across regions. While the image focuses on Methodists specifically, it illustrates broader revival patterns seen among various Protestant denominations. Source.

Moral Urgency and Social Participation

Religious revivals encouraged Americans to see social improvement as a moral duty. Revivalist leaders preached that individuals and communities could actively reform society, linking faith with civic responsibility. This moral energy unified participants around shared commitments to virtue and public action.

Yet revivals also created tensions. Competing denominations sometimes clashed over doctrine and practice, and revivalism’s emphasis on emotional spirituality deviated from more traditional, rationalist religious expressions. Furthermore, the inclusion of women and some Black Americans in revival spaces—and at times in leadership roles—challenged prevailing social norms, sparking resistance from conservative groups.

Reform Movements as Reflections of Idealism and Conflict

Reform movements emerged from the intersection of cultural nationalism and revivalist energy. Many Americans formed voluntary associations to address problems ranging from alcohol consumption to education, poverty, and criminal justice. These associations expressed a belief in human perfectibility and the capacity of citizens to reshape society.

Temperance, Moral Reform, and Voluntary Associations

Temperance advocates argued that alcohol consumption threatened families, moral order, and national progress. Their movement became one of the earliest and most widespread reform efforts, mobilizing men and women across regions. Likewise, moral reform organizations—often led by women—addressed issues such as prostitution and urban vice.

These efforts unified participants around shared moral goals but also exposed divisions over enforcement, social control, and personal freedom. Critics argued that reformers imposed middle-class values on diverse communities, creating cultural and class-based tensions.

Abolitionism and Antislavery Activism

The most polarizing reform movement centered on abolitionism, fueled by both humanitarian ideals and religious conviction. Abolitionists demanded an immediate end to slavery, presenting slavery as incompatible with American republicanism and Christian morality. Their publications, lectures, and petitions spread antislavery sentiment throughout the North.

Abolitionism: A reform movement advocating for the immediate end of slavery on moral, political, and humanitarian grounds.

Abolitionism united committed activists but fractured communities nationwide. Many Northerners opposed slavery yet resisted the perceived extremism of immediatist abolitionists. Southerners denounced abolitionism as a threat to their social order and economic stability, intensifying sectional hostility.

Women’s Rights and Expanding Calls for Equality

Reform movements provided women with opportunities for public leadership and organizational experience. Participation in abolitionism, temperance, and moral reform inspired some women to advocate for expanded rights. The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 emerged from these networks and articulated demands for legal and political equality.

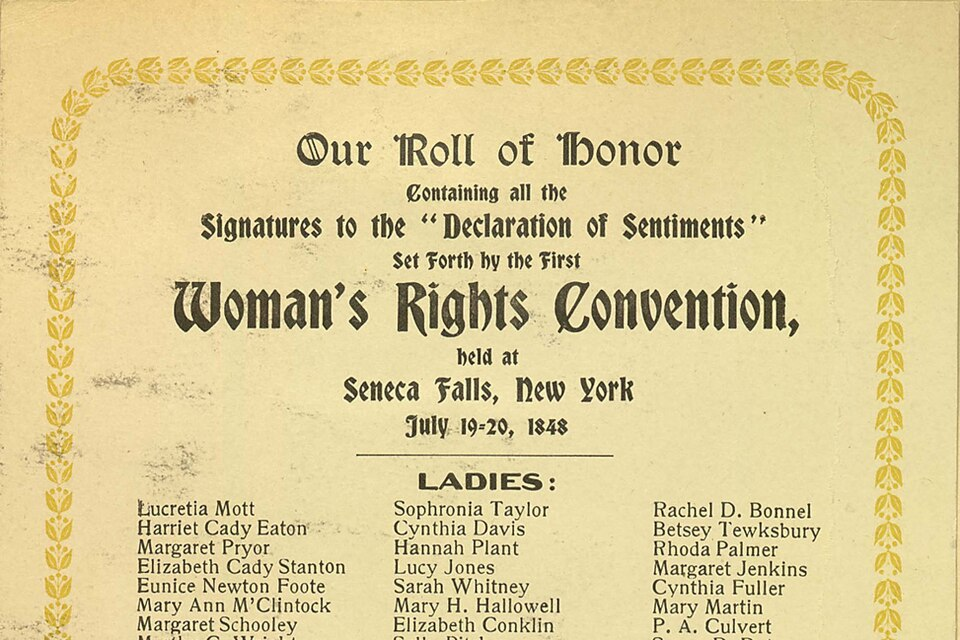

At the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, reformers drafted the Declaration of Sentiments, demanding legal and political equality for women and modeling their grievances on the language of the Declaration of Independence.

This document shows the signature page of the Declaration of Sentiments, adopted at the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. It visually emphasizes that women’s rights reformers framed their demands as a collective moral and political statement. The image includes individual signers’ names, which goes beyond the syllabus but helps illustrate the personal and organized nature of the movement. Source.

These developments revealed contradictions within reform circles. Some reformers argued that women’s rights goals diverted attention from other moral causes, while others insisted that true social improvement required gender equality. The resulting debates underscored how reform movements could simultaneously spark unity and ideological fracture.

Cultural Conflict and Divergent American Ideals

As culture and reform reshaped the nation, Americans forged competing visions of national identity. Many embraced ideals of moral uplift, equality, and democratic participation. Others prioritized social stability, traditional hierarchies, or regional economic systems—especially in the South, where reform movements challenging slavery were fiercely rejected.

Key Sources of Tension

Conflicts between democratic cultural ideals and entrenched racial and gender inequalities

Tensions between evangelical reformers and traditionalists

Sectional divisions intensified by abolitionism and moral critiques of slavery

Disputes over the scope of government authority in promoting social change

Differing regional understandings of religious and cultural values

These tensions revealed that cultural nationalism and reform, while often unifying on the surface, exposed deep fractures in American society. Reform movements helped define the nation’s ideals but also illuminated the contested meanings of freedom, equality, and social responsibility in the early republic.

FAQ

Cultural nationalism encouraged reformers to see the United States as a nation defined not only by political institutions but by shared moral and cultural values. This broadened the sense of national purpose.

Reformers believed that improving society was integral to strengthening the nation’s identity, linking moral progress with patriotism.

It also encouraged the idea that cultural development and social reform were necessary steps toward fulfilling the nation’s democratic ideals.

Voluntary associations created structured networks that allowed ideas, publications, and speakers to circulate widely.

They were effective because:

They provided regular meetings and coordinated campaigns.

They used print culture, including pamphlets and circulars, to reach distant communities.

They enabled cooperation between urban centres and rural towns, giving reform movements a national reach.

These networks made reform efforts more organised and helped unify disparate groups around shared goals.

Internal disagreements over strategy or inclusion often revealed underlying anxieties about gender, race, and class.

For instance, debates within abolitionism over the role of women hinted at broader cultural resistance to female public authority.

Similarly, divisions over whether reform should be gradual or immediate reflected competing visions of social order and political responsibility.

Revivalist preaching emphasised individual responsibility and community improvement, fostering habits that mirrored democratic participation.

These practices encouraged citizens to:

Engage in public meetings.

Advocate for moral causes.

Mobilise neighbours through persuasion rather than coercion.

While focused on spiritual renewal, revivalist culture cultivated skills and civic attitudes that later fed into political activism.

Different regions interpreted reform through the lens of their economic and social structures.

In the North, industrial growth and urbanisation made reform movements more acceptable as responses to visible social challenges.

In the South, reform efforts—particularly abolitionism—were seen as threats to economic stability and racial hierarchy, generating defensive reactions.

These divergent responses deepened sectional identities and made national unity more difficult to sustain.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks):

Identify one way in which the Second Great Awakening contributed to social reform movements in the early nineteenth century United States, and briefly explain why this contribution was significant.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid contribution (e.g., promoting moral responsibility; encouraging formation of voluntary societies; expanding women’s roles in public activism).

1 mark for explaining how revivalist beliefs motivated reform efforts (e.g., emphasis on individual moral improvement or perfectibility).

1 mark for explaining the significance of this contribution (e.g., helped generate widespread participation in movements such as temperance or abolitionism).

Question 2 (4–6 marks):

Evaluate the extent to which cultural and reform movements between 1800 and 1848 created unity within American society. In your answer, consider both unifying and divisive effects.

Mark scheme:

Up to 2 marks for a clear argument addressing the degree of unity produced (e.g., limited unity, significant unity, or unity overshadowed by conflict).

Up to 2 marks for accurate evidence of unifying effects (e.g., shared evangelical values, widespread participation in temperance organisations, national moral discourse).

Up to 2 marks for accurate evidence of divisive effects (e.g., sectional hostility over abolitionism; resistance to women’s rights; denominational and class tensions).