AP Syllabus focus:

‘Explain the context in which sectional conflict emerged from 1844 to 1877.’

The decades between 1844 and 1877 saw accelerating disputes over expansion, slavery, and federal authority, creating conditions in which sectional conflict deepened and ultimately erupted into civil war.

The National Landscape in the 1840s

The United States in the 1840s was a rapidly growing nation shaped by industrialization in the North, plantation expansion in the South, and rising migration from Europe. These developments sharpened economic and cultural contrasts. While northern regions expanded manufacturing and free labor, southern states entrenched a slave-based agricultural economy centered on cotton.

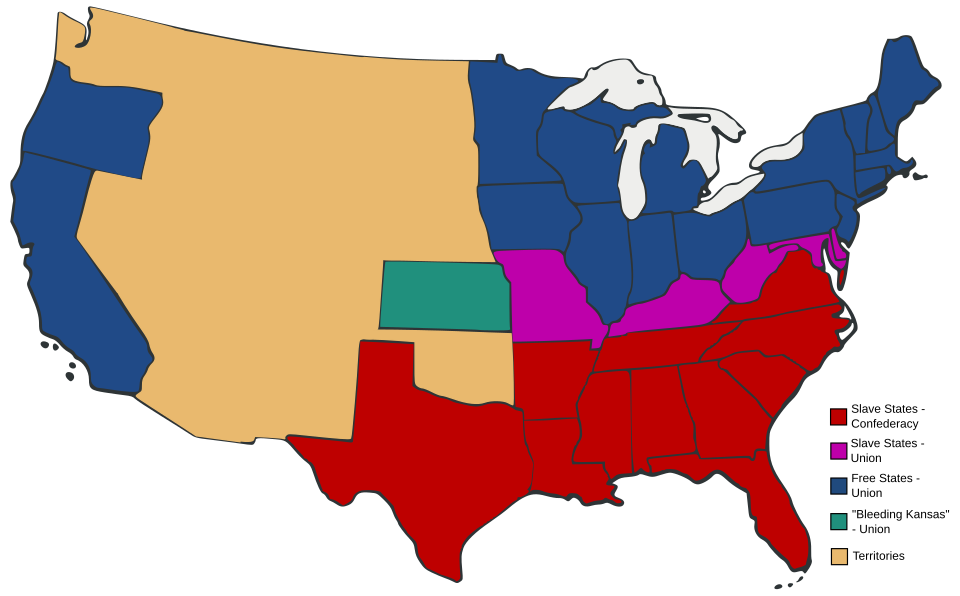

Map distinguishing free, slave, and territorial regions before the Civil War. It illustrates the sharp geographic division between free-labor and slave-labor systems. Some territorial details extend beyond this subtopic but help contextualize sectional contrasts in the mid-19th century. Source.

These divergent systems produced conflicting social orders and political goals, especially as the nation contemplated further territorial expansion.

Ideological Divisions and the Question of Expansion

Debates over expansion provided a central stage on which sectional tensions played out. The ideology of Manifest Destiny, first widely articulated in the 1840s, held that Americans were destined to settle the continent.

Manifest Destiny: The belief that American expansion across the continent was both justified and inevitable, rooted in ideas of national mission and perceived cultural superiority.

Many northerners supported expansion for economic opportunity, while many southerners viewed new land as essential for extending enslaved labor and preserving political balance. These competing visions made expansion an arena of conflict rather than unity.

War, Territorial Growth, and Rising Tensions

The Impact of the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (1846–1848), fought amid expansionist enthusiasm, dramatically reshaped political debates.

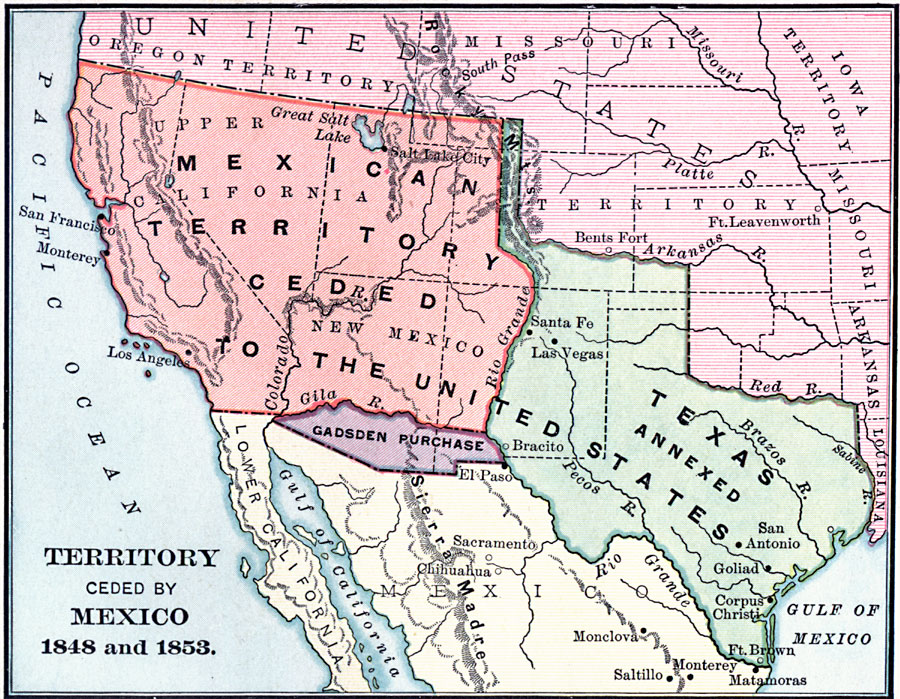

Map showing the territory ceded by Mexico to the United States between 1848 and 1853, including the Mexican Cession and the Gadsden Purchase. It highlights newly acquired lands central to debates over slavery’s extension. The map includes additional regional detail not required by the syllabus but useful for geographic context. Source.

Victory added vast western territory, but it also revived the central question: Would slavery expand into these lands?

The Wilmot Proviso of 1846, which attempted to ban slavery from any territory taken from Mexico, became a symbolic flashpoint. Although it never passed, it signaled unmistakably that national political compromise was weakening.

Political Attempts to Contain Division

Throughout the late 1840s and 1850s, national leaders sought temporary political solutions.

Key tensions emerged as:

Northern free-soil advocates argued slavery threatened the economic independence of free laborers.

Southern leaders insisted that restricting slavery violated constitutional protections.

Westward settlement created new communities that demanded territorial organization and statehood.

The Breakdown of Political Balance

Strains on the Two-Party System

By the early 1850s, differences over expansion and slavery destabilized the Second Party System, which had previously encouraged national coalitions. As debates intensified, established parties struggled to bridge sectional divides.

Important developments included:

The collapse of the Whig Party, largely over slavery disagreements.

The emergence of sectional parties, including the Republican Party, which opposed the expansion of slavery into the territories.

Increasing polarization in Congress, including physical violence such as the 1856 caning of Senator Charles Sumner.

These shifts underscored how expansion-related debates had eroded the unifying structures of national politics.

Growing Social and Cultural Divisions

Migration, Ethnicity, and Nativism

Large-scale immigration, especially from Ireland and Germany, reshaped northern cities and fueled cultural debates. Many immigrants joined the free-labor economy, strengthening northern demographics. In contrast, southern society remained more rural and tied to enslaved labor.

This influx also produced a rise in nativist sentiment. Groups such as the Know-Nothing Party opposed immigrant political influence and Catholic presence, generating an additional layer of national tension—one that widened sectional differences because immigration was concentrated overwhelmingly in the North.

Abolition, Resistance, and Southern Defensiveness

Abolitionists, both Black and white, intensified efforts to expose the moral and political contradictions of slavery. Through antislavery literature, public activism, and direct assistance via the Underground Railroad, they contributed to an increasingly national conversation about the institution.

Many white southerners reacted by hardening pro-slavery arguments. They claimed slavery was a positive good and essential to southern society, and they insisted that federal restrictions were unconstitutional. These opposing views over morality, economy, and constitutional interpretation broadened the sectional divide.

Toward Secession and Civil War

The Failure of Compromise

Despite repeated attempts at national compromise, including high-profile agreements such as the Compromise of 1850, political leaders could not create lasting peace. Expansion continued to raise questions that no compromise could fully settle. The Kansas–Nebraska Act (1854), which opened new territories to popular sovereignty, led to violent conflict in “Bleeding Kansas,” demonstrating the limits of legislative solutions.

Secession and the Transformation of Conflict

By 1860, with Abraham Lincoln’s election on a free-soil platform, southern states began voting to secede. Most seceded by early 1861, sparking the Civil War. The war intensified federal power, reshaped the meaning of citizenship, and accelerated debates about national authority—debates that continued into Reconstruction, when the federal government attempted to reorder southern society while confronting violent resistance and contested definitions of freedom and rights.

Reconstruction and Continuing Sectionalism

From 1865 to 1877, Reconstruction policies tried to reintegrate the South and secure the rights of formerly enslaved people. Constitutional changes such as the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments redefined national citizenship and federal-state relations, but fierce southern opposition and waning northern commitment limited long-term progress. These unresolved battles over freedom, rights, and power preserved sectional tensions well beyond the war’s end, anchoring the historical context for conflict throughout the entire period from 1844 to 1877.

FAQ

Racial hierarchy underpinned southern justifications for slavery, with enslaved people depicted as inherently suited to servitude. This ideological framework reinforced claims that slavery was a positive good rather than a temporary economic system.

In the North, although prejudice persisted, racial hierarchy was less central to economic structures. This divergence contributed to incompatible visions of national identity.

Most migrants sought land, opportunity, and autonomy, but their settlement forced Congress to decide how new territories would be organised.

These decisions inevitably returned to slavery, as political power in Congress depended on the balance of free and slave states. Thus, even apolitical movement westward intensified sectional stakes.

Congress became increasingly confrontational as compromise broke down. Debates grew more personal and violent, signalling a weakening commitment to national unity.

Notable incidents included the use of threats, walkouts, and eventually physical assaults, demonstrating that political institutions were struggling to contain regional hostility.

Expanding print networks created distinct northern and southern information environments. Newspapers framed events through sectional lenses, reinforcing regional grievances.

Abolitionist and pro-slavery publications circulated increasingly extreme rhetoric, making moderation less politically viable and encouraging the belief that the opposing section threatened core values.

Northern industrial growth suggested a future national economy based on wage labour and manufacturing. Southern leaders feared this would marginalise the plantation system.

These concerns heightened anxieties that federal policy would gradually undermine slavery, encouraging stronger demands for constitutional protections and, eventually, for secession.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks):

Identify one major factor between 1844 and 1877 that contributed to the emergence of sectional conflict in the United States, and briefly explain how it increased tensions.

Mark scheme:

1 mark – Identifies an appropriate factor (e.g., westward expansion, the Mexican–American War, debates over slavery in new territories, rise of abolitionism, emergence of the Republican Party).

1 mark – Provides a clear explanation of how this factor contributed to sectional conflict (e.g., disagreement over slavery’s expansion, political polarisation).

1 mark – Uses historically accurate detail to support the explanation (e.g., reference to the Wilmot Proviso, Kansas–Nebraska Act, or secession debates).

Question 2 (4–6 marks):

Explain how developments between 1844 and 1877 created the political, economic, and ideological context for sectional conflict. In your answer, refer to at least two different historical developments from this period.

Mark scheme:

1–2 marks – Demonstrates a basic understanding of sectional conflict with limited detail.

3–4 marks – Explains at least two developments (e.g., Mexican–American War, rise of free-soil ideology, growth of abolitionism, breakdown of the Second Party System, Reconstruction debates) and links them to sectional conflict with reasonable accuracy.

5–6 marks – Provides a well-developed explanation showing how political, economic, and ideological factors interacted to intensify sectionalism; uses specific, relevant evidence (e.g., Wilmot Proviso, Republican Party formation, Compromise of 1850, Kansas–Nebraska Act, secession); shows clear analytical connections between developments and the broader historical context.