AP Syllabus focus:

‘An anti-Catholic nativist movement grew, aiming to limit new immigrants’ political power and cultural influence.’

During the mid-19th century, rising immigration and shifting cultural identities fueled nativist sentiment and produced influential anti-Catholic political movements that reshaped American politics and regional tensions.

Nativism in Antebellum America

Nativism—hostility toward immigrants perceived as threatening existing social, cultural, or political norms—surged in the 1840s and 1850s as immigration from Ireland and Germany intensified. Many Americans feared that newcomers undermined republican values, competed for jobs, and would politically align with the Democratic Party, whose urban machines often supported immigrant communities. These anxieties intersected with religious prejudice, making anti-Catholicism a defining core of nativist ideology.

Nativism: A political and social movement favoring native-born Americans over immigrants, often expressing hostility toward groups seen as culturally or politically incompatible.

The rapid demographic change in northern cities created an environment in which old cultural suspicions—particularly anti-Catholic fears inherited from earlier Protestant traditions—became politically mobilized. As the nation confronted questions about slavery, western expansion, and party realignment, nativism added an additional layer of sectional and ideological conflict.

Why Catholics Became Targets

Religious and Cultural Tensions

Many Protestant Americans believed that Catholicism represented authoritarianism incompatible with republican self-government.

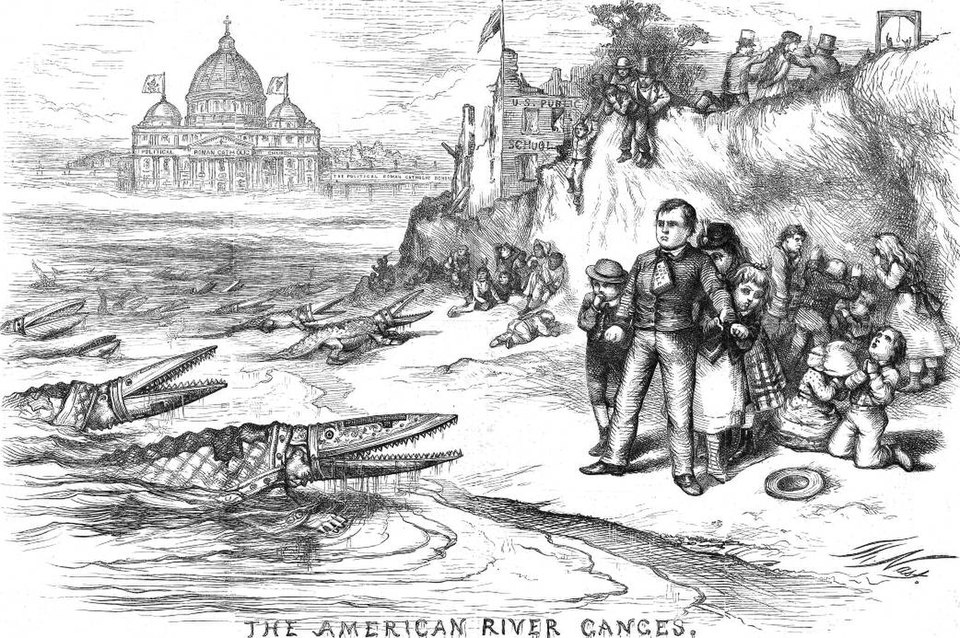

This cartoon shows mitred crocodile-like Catholic bishops emerging from the “American River Ganges” toward schoolchildren, capturing Protestant fears of papal influence over public education and democratic institutions. The imagery highlights anxieties that Catholic authority threatened republican self-rule. Although published in the 1870s, it reflects the long-lasting impact of earlier anti-Catholic nativism. Source.

Economic Anxiety

Economic downturns, especially the Panic of 1857, intensified competition for labor. Immigrants—often willing to work for lower wages—were viewed as undermining the economic standing of native-born workers.

Political Fears

Nativists believed that newly arrived immigrants, concentrated in growing urban areas, could be mobilized by political machines. Their rapid naturalization raised fears that immigrants would distort elections, especially in northern states where population shifts affected congressional representation.

Anti-Catholic Politics and Public Mobilization

Growth of Anti-Immigrant Organizations

Nativist sentiment produced a wide network of associations, reading rooms, and vigilance committees throughout northern cities. These groups coordinated propaganda efforts, sponsored lectures, and encouraged boycotts of Catholic businesses or schools. Their activities helped solidify anti-immigrant rhetoric within local politics.

The Know-Nothing Movement

The most influential political expression of nativism was the American Party, popularly known as the Know-Nothing Party.

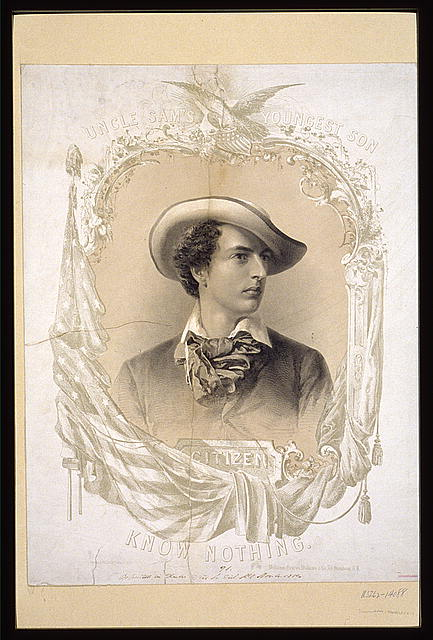

This illustration portrays “Citizen Know Nothing,” an idealized nativist figure surrounded by American patriotic emblems. It shows how the movement framed itself as defending the nation from perceived immigrant and Catholic threats. Although symbolic rather than policy-focused, it communicates the self-image promoted by the Know-Nothing Party. Source.

American Party (Know-Nothing Party): A mid-1850s political movement centered on nativist and anti-Catholic principles, seeking to restrict immigrant political power.

The Know-Nothings derived their name from the semisecret nature of their early organization, whose members claimed to “know nothing” when questioned. Their platforms often appealed to widespread concerns about morality, political corruption, and cultural change.

Core Policy Goals

Longer naturalization periods, often extending citizenship requirements from five to twenty-one years.

Restrictions on immigrant voting, including literacy tests.

Exclusion of foreign-born individuals from public office, especially at the state and municipal levels.

Support for Protestant-based public schooling, coupled with opposition to funding Catholic institutions.

Electoral Impact

The Know-Nothing Party briefly achieved major success, winning state elections in Massachusetts and influencing Congress during the mid-1850s. Their rise reflected both cultural anxiety and dissatisfaction with the existing two-party system, which was fracturing under the pressure of slavery expansion debates.

Anti-Catholic Violence and Social Conflict

Nativist rhetoric often fueled real-world conflict.

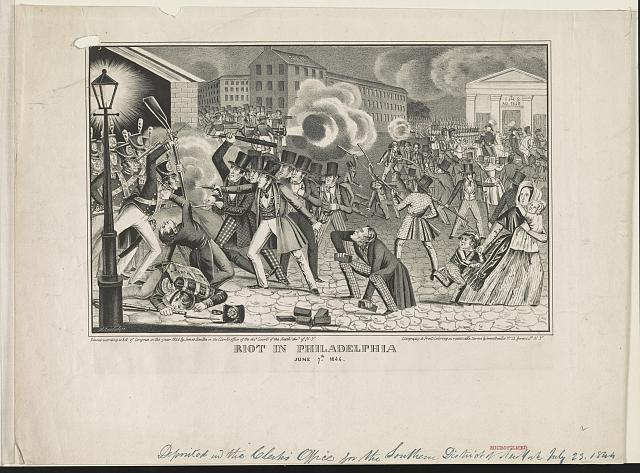

This lithograph depicts militia confronting rioters during the 1844 Philadelphia nativist riots, which were fueled by anti-Catholic sentiment. The burning buildings and street fighting illustrate how cultural and religious hostility escalated into urban violence. Though specific to Philadelphia, it reflects broader tensions associated with nativism in the era. Source.

Riots erupted in cities such as Philadelphia and Louisville, where Protestant mobs attacked Catholic neighborhoods, churches, and immigrant groups.

Political intimidation discouraged immigrant political participation and reinforced ethnic segregation in urban areas.

Sensational literature, including widely circulated conspiracy tracts, depicted priests and convents as sinister threats, inflaming prejudice.

These episodes underscored the volatility of social relations in growing urban centers during a period of intense national transformation.

Connections to Sectional Politics

As the slavery controversy intensified, nativism intersected with—but never fully replaced—sectional divisions. The Know-Nothing Party attempted to avoid direct engagement with slavery by emphasizing cultural unity among native-born Protestants. Yet this strategy quickly unraveled.

Decline of the Know-Nothing Movement

Several factors contributed to the movement’s collapse by the late 1850s:

The Kansas–Nebraska Act shifted national attention toward slavery in the territories, overshadowing nativist priorities.

Internal divisions emerged between northern and southern factions over the place of slavery in party platforms.

The rise of the Republican Party, which mobilized voters around free-soil ideology and opposition to the expansion of slavery, drew support away from nativist organizations.

Lasting Influence

Although the Know-Nothings dissolved, nativism persisted. Anti-Catholic attitudes remained embedded in social institutions and influenced later political movements, including late-19th-century immigration restriction campaigns. The 1840s–1850s thus marked the first major period in which nativism translated into national political power, shaping the broader landscape of partisan realignment and cultural conflict on the eve of the Civil War.

FAQ

Many Protestants viewed public schools as institutions that transmitted civic virtue and Protestant moral values. Catholic requests for public funding of separate schools, or for changes to Bible-reading practices, were perceived as attempts to undermine this cultural foundation.

As a result, controversies over schooling became symbolic battles about American identity, making education one of the most visible arenas of anti-Catholic activism.

Nativist publishers circulated sensational stories claiming Catholic clergy sought political dominance or moral corruption. These texts often blended fearmongering with fabricated testimonies from supposed ex-priests or nuns.

Circulation of these materials helped standardise anti-Catholic narratives across regions, giving the movement cohesion and reach beyond local communities.

Yes. Northern cities experienced rapid immigration, making anti-Catholic activism more prominent and politically effective there.

In the South, smaller Catholic populations meant nativism was weaker, though some southerners embraced it as part of a broader defence of Protestant hierarchy. However, competition with slavery debates limited nativism’s political traction in the region.

Catholics organised self-defence associations, petitioned local officials, and expanded charitable networks to support recent immigrants. Parish leaders encouraged community solidarity, often centred on the church as a protective institution.

Over time, Catholic newspapers and civic groups emerged to counter stereotypes and advocate for equal political rights.

The intensification of the slavery crisis overshadowed cultural and religious issues, pushing nativist politics aside. The emergence of the Republican Party also drained support from nativist parties by offering clearer positions on national conflicts.

Although anti-Catholic sentiment persisted socially, it no longer served as the primary organising force in national politics.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why nativist groups in the 1840s and 1850s opposed Catholic immigrants.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., fear of Catholic political influence).

+1 mark for explaining how this reason motivated nativist hostility.

+1 mark for using specific contextual detail (e.g., concerns about allegiance to the Pope, worries about Democratic Party mobilising immigrant votes, or fears regarding Catholic influence over public schools).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how anti-Catholic attitudes shaped political developments in the United States during the 1840s and 1850s.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying at least one major political development linked to anti-Catholic sentiment (e.g., the rise of the Know-Nothing Party).

+1–2 marks for explaining how anti-Catholicism contributed to that development (e.g., shaping party platforms, calls for stricter naturalisation laws, or efforts to restrict immigrant voting).

+1–2 marks for integrating relevant historical evidence (e.g., nativist riots, popular literature attacking Catholic influence, electoral successes in Massachusetts).

+1 mark for showing analytical depth (e.g., linking anti-Catholic politics to broader patterns such as urbanisation, political realignment, or public-school debates).