AP Syllabus focus:

‘Defenders of slavery argued from racial doctrines, claimed slavery was a positive social good, and insisted slavery and states’ rights were protected by the Constitution.’

Pro-slavery advocates in the antebellum United States constructed complex ideological defenses of slavery, invoking racial hierarchy, constitutional interpretation, and states’ rights to justify its continuation against growing Northern criticism.

Pro-Slavery Thought in the Mid-19th Century

Pro-slavery arguments intensified during the 1840s and 1850s as national debates over the expansion of slavery sharpened sectional divisions. Southern leaders saw the institution as essential to their economy, social order, and political autonomy, prompting a sweeping intellectual campaign to portray slavery not merely as necessary, but beneficial and constitutionally protected.

Racial Doctrines as a Justification

A central component of pro-slavery ideology rested on claims of innate racial hierarchy, asserting that African Americans were biologically inferior and naturally suited for enslavement. These ideas drew on pseudoscience, selective readings of scripture, and widespread cultural assumptions in the South.

Racial Doctrine: The belief that races possess inherent and unequal characteristics, used by pro-slavery advocates to justify African Americans’ permanent subordination.

These racial claims helped defenders of the institution argue that slavery was essential for maintaining social stability, moral discipline, and what they believed to be the appropriate ordering of Southern society.

Slavery as a “Positive Good”

By the 1830s and continuing into the antebellum decades, Southern politicians and intellectuals increasingly insisted that slavery was not a temporary evil but a “positive good”—a social system that benefited all parties involved. They framed enslaved labor as superior to Northern wage labor, which they labeled exploitative and unstable.

Positive Good Theory: The pro-slavery argument that slavery provided mutual benefits, claiming enslaved people gained security while enslavers gained labor.

Pro-slavery writers such as George Fitzhugh and political leaders like John C. Calhoun argued that enslaved African Americans were better cared for than free laborers in the industrial North.

Portrait of John C. Calhoun, a leading Southern theorist of states’ rights whose pro-slavery arguments shaped sectional debates. Calhoun defended slavery as essential to Southern society and promoted doctrines such as nullification to resist federal antislavery measures. This image helps illustrate an influential architect of pro-slavery constitutional thought. Source.

These defenses were deeply intertwined with paternalism, a hierarchical ideology asserting that enslavers acted as benevolent guardians.

Constitutional Claims and the Defense of Slavery

Many Southern leaders grounded their position in constitutional interpretation, asserting that the federal government lacked authority to interfere with slavery in states or territories. They argued that:

The Constitution recognized enslaved people as property.

Property rights were protected under the Fifth Amendment.

Federal attempts to restrict slavery violated the agreement between states at the nation’s founding.

Supporters claimed that the Three-Fifths Compromise and the Fugitive Slave Clause demonstrated the Framers’ intention to protect slaveholding interests. From this perspective, restricting slavery’s expansion threatened the balance of power and the constitutional rights of Southern states.

States’ Rights and Sectional Constitutionalism

Invoking states’ rights, Southern politicians insisted that each state retained sovereignty over its domestic institutions. They used this principle to resist federal restrictions, arguing that the Union was a voluntary compact among states.

States’ Rights: The constitutional principle asserting that states possess independent authority, limiting federal power over internal state matters.

Pro-slavery advocates contended that if the federal government could regulate or abolish slavery, it could intrude upon any state policy. Thus, defending slavery became synonymous with defending state autonomy itself. This contributed to escalating tensions as Northern antislavery activism grew.

Scriptural and Moral Claims

Many pro-slavery thinkers cited religious justifications. They argued that biblical texts acknowledged slavery and that patriarchal models in scripture affirmed hierarchical social relationships. Specific claims included:

Slavery existed in ancient societies praised in the Bible.

Apostolic teachings encouraged obedience among enslaved people.

Christian masters, they claimed, provided moral guidance and uplift.

These arguments aimed to counter abolitionists’ moral critiques, placing slavery within a divinely sanctioned social order.

Economic Arguments and the Defense of Southern Society

Pro-slavery advocates insisted that the Southern economy—based on cotton, rice, and tobacco—required enslaved labor. They believed emancipation would collapse the agricultural system, destroy capital investment, and unleash economic chaos. According to this logic:

Plantation production depended on controlled, disciplined labor.

Wage labor could not meet the needs of large-scale Southern agriculture.

Enslavers’ wealth formed the backbone of regional prosperity.

These economic claims intertwined with fears of class conflict and racial upheaval. Southerners pointed to slave rebellions, such as the 1831 Nat Turner uprising, to argue that ending slavery would produce widespread violence.

Political Mobilization Around Pro-Slavery Positions

By the 1850s, these arguments shaped Southern political strategy and sharpened sectional polarization. Key developments included:

Opposition to the Wilmot Proviso and other attempts to restrict slavery’s expansion.

Demands for federal enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act, framed as constitutional duty.

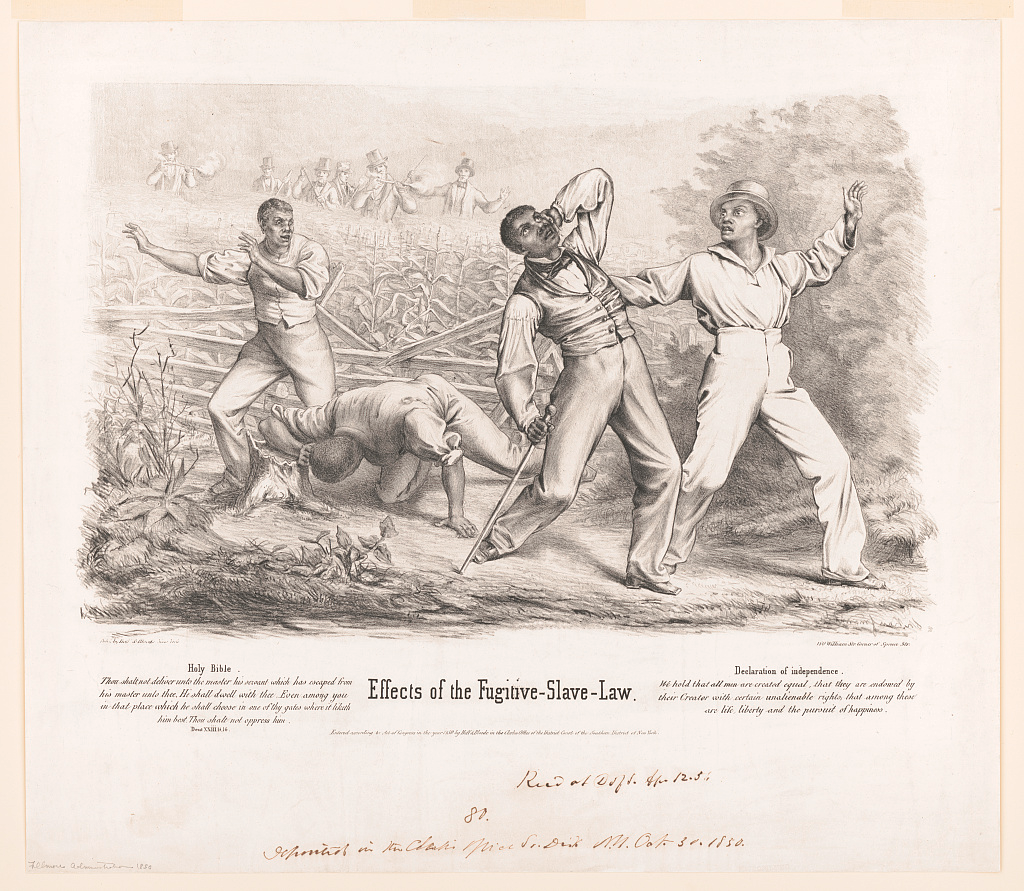

Lithograph titled “Effects of the Fugitive-Slave-Law,” depicting violent enforcement of the 1850 statute. Although created from an abolitionist perspective, it visualizes how federal authority was deployed to protect slavery in the name of constitutional obligation. Scriptural and political quotations beneath the image provide additional critique beyond syllabus requirements. Source.

Growing support for secession as the ultimate expression of states’ rights.

Southern politicians argued that Northern hostility to slavery endangered the constitutional order. Protecting slavery became a central goal of political parties such as the Democratic Party’s Southern wing.

Slavery, Honor, and Regional Identity

Pro-slavery ideology also blended with Southern cultural values emphasizing honor, hierarchy, and patriarchal authority. Slavery structured social relationships not only between enslavers and enslaved people but within white society, reinforcing distinctions of class and status. Many Southern whites, including non-slaveholding farmers, accepted pro-slavery arguments because they aligned with aspirations to racial supremacy and fears of social leveling.

The Inseparability of Slavery and States’ Rights

While states’ rights formed a consistent rhetorical theme, they were most often invoked when protecting slavery itself. Southern leaders rarely emphasized states’ rights independently; instead, they used the principle as a defense against perceived Northern attempts to undermine the institution. As sectional tensions escalated, pro-slavery constitutionalism transformed into a justification for disunion, showing how deeply intertwined slavery was with broader arguments about authority, identity, and national power.

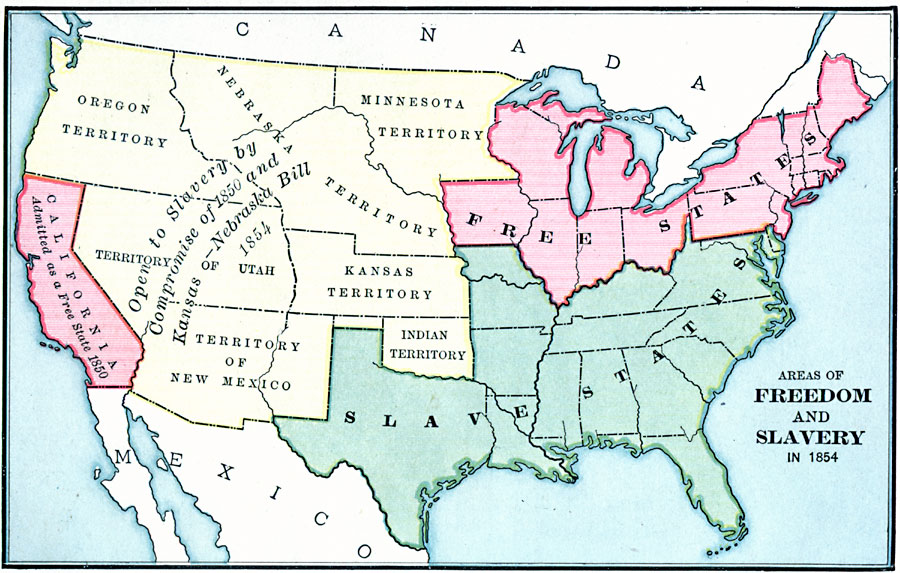

Map of the United States in 1854 showing free states, slave states, and territories open to slavery. It visually reinforces the sectional nature of pro-slavery constitutional claims by depicting how geographic divisions shaped political conflict. The map’s reference to the Kansas–Nebraska Act provides helpful broader context slightly beyond the immediate syllabus scope. Source.

FAQ

Pro-slavery writers selectively used early anthropological claims to argue that Africans belonged to a permanently inferior racial category. These arguments drew on pseudoscientific measurements such as skull size or facial angle, which they claimed demonstrated intellectual or moral inferiority.

They also cited ideas like polygenesis, the belief that human races had separate origins, to reject arguments for natural equality.

Such uses of “science” helped shield slavery from moral criticism by framing inequality as biological rather than created by enslavement.

Many non-slaveholding whites saw slavery as essential to maintaining racial hierarchy, which granted them status above all Black people regardless of wealth.

They also believed slavery prevented competition for jobs and land, preserving economic opportunity for whites.

Social pressure, political culture, and churches that reinforced pro-slavery teachings further strengthened loyalty to the system.

They argued that the Revolution had been fought to protect local autonomy against distant authority, claiming this legacy justified resisting federal antislavery efforts.

Pro-slavery leaders said the Constitution embodied a compact among sovereign states, and that preserving slavery was consistent with the Founders’ intention to protect property rights.

By framing themselves as defenders of the Revolutionary tradition, they sought moral legitimacy for their sectional position.

Clergy crafted sermons emphasising obedience, hierarchy, and the duty of enslaved people to accept their condition. They cited biblical figures who owned slaves and passages encouraging servitude.

Ministers also reassured slaveholders that Christian paternalism made slavery morally acceptable.

This blending of faith and social order helped shape a powerful cultural defence of slavery across Southern communities.

They described wage labour as chaotic, exploitative, and unstable, claiming that workers in factories suffered more hardship than enslaved people who, they argued, received lifetime security.

Pro-slavery writers insisted that slavery eliminated class conflict by placing labourers under the permanent authority of “responsible” masters.

This comparison helped justify slavery as a more humane and socially harmonious system.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one argument used by antebellum Southern defenders of slavery to justify the institution, and briefly explain how this argument supported their broader social or political aims.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks.

• 1 mark for identifying a valid pro-slavery argument (e.g., racial hierarchy, positive good theory, economic necessity).

• 1 mark for explaining how the argument justified slavery (e.g., claiming enslaved people were suited to bondage, or that slavery was beneficial to society).

• 1 mark for linking the argument to wider aims (e.g., preservation of Southern social order, protection of political power, resistance to Northern criticism).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how pro-slavery advocates used both constitutional interpretation and states’ rights ideology to defend slavery in the antebellum United States. In your answer, refer to specific claims or examples.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks.

• 1–2 marks for describing pro-slavery constitutional arguments (e.g., property rights in enslaved people, Fifth Amendment protection, reliance on clauses such as the Fugitive Slave Clause).

• 1–2 marks for explaining states’ rights ideology (e.g., claims that states retained sovereignty over domestic institutions, compact theory of the Union).

• 1–2 marks for integrating specific examples or consequences (e.g., defence of the Fugitive Slave Act, opposition to federal limits on slavery’s expansion, claims that federal intervention violated the founding compact).