AP Syllabus focus:

‘Black and white abolitionists waged a visible campaign against slavery, aiding escapes and sometimes expressing a willingness to use violence.’

Abolitionism in the mid-19th century grew into a powerful, diverse movement challenging slavery’s legality and morality, using persuasive arguments, grassroots resistance, and, at times, direct violent action.

Moral Arguments against Slavery

Abolitionists developed a multilayered moral critique that framed slavery as fundamentally incompatible with American values and natural rights. Their appeals shaped national debate by emphasizing ethical responsibility and human equality.

Religious and Ethical Claims

Many abolitionists invoked Christian moral law to argue that slavery violated divine principles of justice and human dignity. Preachers, reformers, and lay activists circulated sermons and pamphlets that condemned enslavement as a sin that corrupted both enslavers and the nation.

The Humanitarian Appeal

Black and white reformers publicized firsthand testimonies to expose the cruelty of bondage.

Narratives by formerly enslaved people highlighted the brutality of forced labor, family separation, and racial inequality.

Activists used moral persuasion to convince Northerners that tolerating slavery contradicted the ideals of liberty promoted in the Declaration of Independence.

Natural Rights: Rights that individuals inherently possess—such as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—considered universal and not granted by governments.

Abolitionists frequently asserted that enslaved people were being denied these rights, strengthening calls for nationwide emancipation.

The Role of Free Black Abolitionists

Free African Americans played a crucial role by providing lived expertise on racial oppression. Leaders such as Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and David Walker argued that slavery threatened not only the enslaved but also the moral character of the republic.

Portrait of Frederick Douglass around 1879, highlighting his role as a leading abolitionist writer and orator. His firsthand testimony of slavery’s brutality shaped national debates about freedom and equality. The image contains no additional content beyond his likeness, keeping focus on his historical significance. Source.

Their speeches and publications broadened the movement’s reach and enhanced its credibility.

Resistance: Everyday, Organized, and Collective

Abolitionism was not solely a matter of rhetoric; it included active, often clandestine resistance conducted by both enslaved people and their allies.

Everyday Resistance by Enslaved People

Enslaved African Americans engaged in forms of everyday resistance, a term describing subtle but impactful acts challenging the slave system.

Work slowdowns

Sabotaging equipment

Secret education

Maintaining cultural and familial bonds in defiance of slaveholder control

Everyday Resistance: Small-scale acts of defiance by subordinated groups intended to undermine oppressive systems without open confrontation.

These actions revealed that enslaved people were not passive but continually contested the system that constrained them.

The Underground Railroad

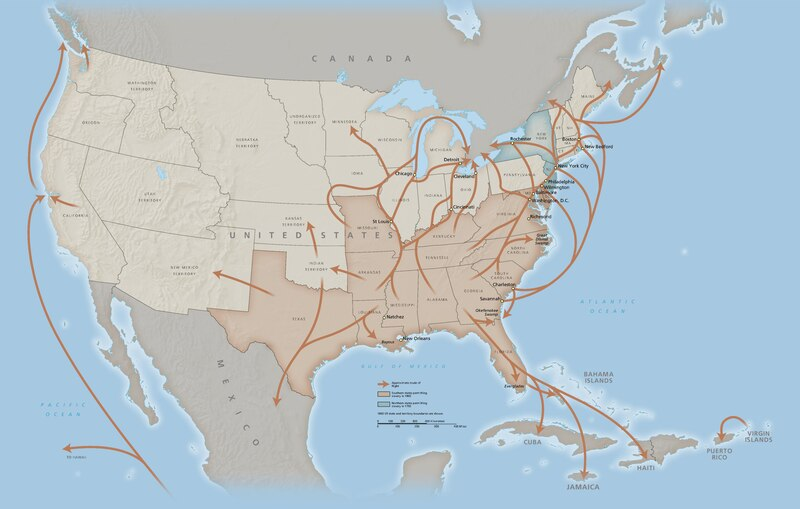

The movement’s most visible collaborative resistance took form in the Underground Railroad, a secret network aiding enslaved people seeking freedom.

Conductors, including Harriet Tubman, guided escapees along routes to free states or Canada.

Stations provided shelter, supplies, and information.

Community networks, including free Black families, Quakers, and sympathetic Northerners, risked arrest and fines to assist fugitives.

Bulletins, abolitionist newspapers, and speeches praised these efforts and emphasized that aiding escapes was a moral duty when laws upheld slavery.

Map depicting major Underground Railroad routes from Southern slave states to free states and Canada. Arrows and labels illustrate how escape networks operated across regions, reinforcing the movement’s coordinated yet clandestine nature. Some geographic details exceed the scope of the notes but directly support understanding of escape pathways. Source.

Willingness to Use Violence

While many abolitionists relied on moral persuasion or legal action, a minority accepted or endorsed violence as a legitimate response to slavery’s inherent brutality.

Militant Abolitionism

Militant activists argued that slavery was maintained through violence and thus could only be overthrown by force.

David Walker’s Appeal (1829) urged enslaved people to resist violently if necessary.

Some abolitionists defended armed resistance in cases where enslaved individuals fought back against slave catchers or brutal overseers.

One sentence separates the themes before the next definition block, providing necessary context and continuity.

Militant Abolitionism: A strand of antislavery activism advocating the use of force or insurrection to destroy the slave system when peaceful means proved ineffective.

John Brown and Direct Action

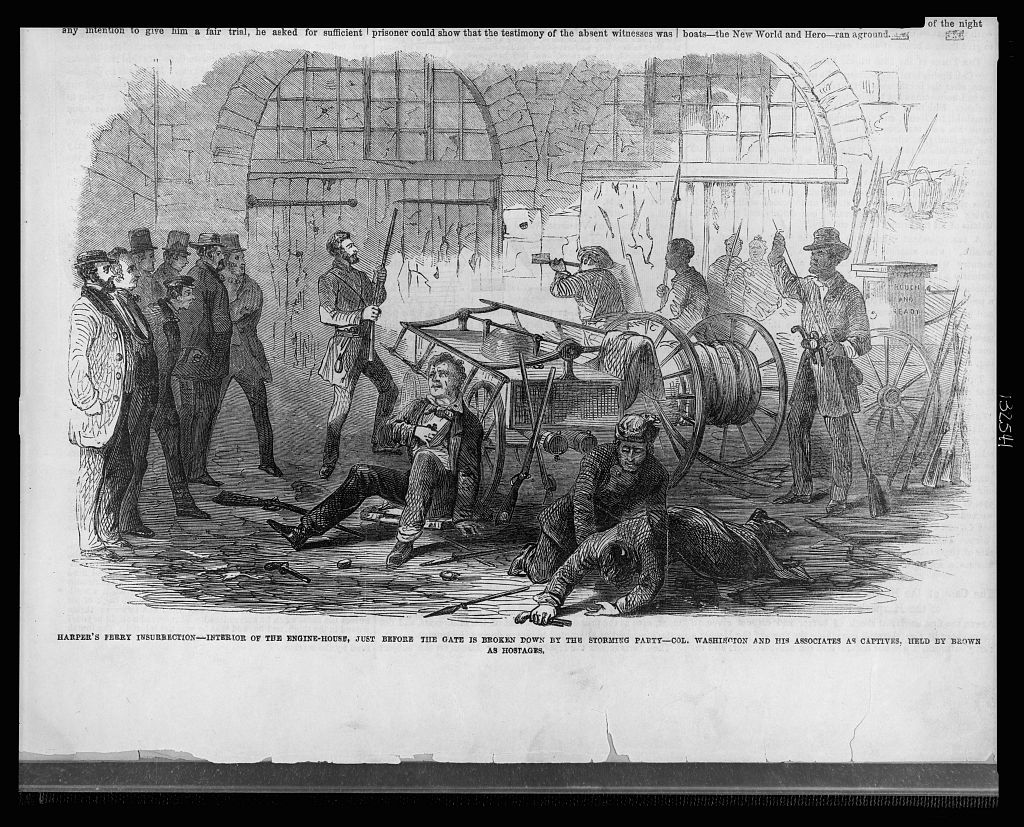

John Brown embodied the most extreme form of abolitionist militancy. Although controversial among moderates, his actions symbolized the willingness of some to risk war to end slavery.

Brown led the Pottawatomie Creek killings in Kansas in 1856, targeting proslavery settlers during violent sectional clashes.

His 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry sought to spark a widespread slave uprising by seizing federal weapons.

Engraving of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, showing Brown and his followers defending the engine house while surrounded by hostages and wounded men. The image captures the tense, violent atmosphere of the failed insurrection that deepened sectional tensions. Some visual specifics exceed AP requirements but all relate directly to the historical event. Source.

Although the raid failed and Brown was executed, his martyr-like status among abolitionists heightened tensions before the Civil War.

Violence within the Broader Movement

Even within predominantly nonviolent organizations, debates erupted regarding the boundaries of lawful protest. Some activists justified defensive violence, especially as fugitive slave laws intensified conflict in Northern communities.

Resistance to slave-catcher incursions sometimes resulted in armed confrontations.

Abolitionists in cities like Boston, Syracuse, and Philadelphia organized vigilance committees to protect fugitives, occasionally clashing with federal officers.

The Visibility of the Abolitionist Campaign

The abolitionist campaign became increasingly visible in American society, influencing political culture and shaping sectional divisions that would eventually lead to war.

Print Culture and Public Advocacy

Abolitionists harnessed print technology to maintain a strong public presence.

Newspapers such as The Liberator, published by William Lloyd Garrison, delivered uncompromising antislavery arguments.

Broadsides and illustrated pamphlets depicted the horrors of slavery to mobilize public support.

Antislavery lectures and petition campaigns helped circulate ideas across urban and rural communities alike.

Political Pressure and Social Reform Networks

Though the movement itself was not a unified political party, its members influenced major reform networks.

Abolitionists collaborated with women’s rights activists, temperance advocates, and evangelical reformers who saw slavery as part of a broader struggle for human uplift.

Through petitions, lobbying, and public meetings, they pressured Congress and state governments to reconsider slavery’s place in American law and society.

Abolitionism’s blend of moral conviction, everyday resistance, and, in some cases, violent determination made it one of the most influential reform movements of the antebellum era, shaping national debates and accelerating the coming of the Civil War.

FAQ

Abolitionists adapted their arguments depending on whether they addressed religious groups, political leaders, or working-class Northerners.

For religious audiences, they emphasised Christian doctrine, highlighting slavery as a sin that corrupted national morals.

For political audiences, they stressed contradictions between slavery and republican principles.

Among working people, reformers drew attention to the violence and exploitation inherent in slavery, presenting it as an affront to human dignity and economic fairness.

Black women such as Harriet Jacobs, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and Charlotte Forten Grimké developed strategies combining community organisation, public lecturing, and discreet assistance to fugitives.

They also:

Raised funds within Black communities to support escape networks

Organised reading circles to circulate antislavery literature

Provided shelter and logistical support for people escaping slavery

Their work often operated outside formal abolitionist societies, giving them flexibility to act independently of male-led organisations.

Because secrecy was essential for protecting escape routes, organisational structures were decentralised and based on trust rather than formal leadership.

Information travelled through:

Oral communication using coded language

Safe houses known only to select local participants

Church networks and maritime contacts

This clandestine structure made the system resilient. If one route was exposed, others could still operate without revealing the network as a whole.

Southern leaders portrayed militant abolitionists as existential threats, using incidents like John Brown’s raid to justify harsher policing of both enslaved and free Black populations.

They expanded surveillance, restricted movement, and tightened laws against teaching enslaved people to read.

Public rhetoric increasingly framed Northerners as complicit in violent plots, fuelling sectional distrust and reinforcing the belief that coexistence within the Union was becoming impossible.

Moderates feared that association with violence would undermine public sympathy and alienate potential allies in churches, legislatures, and the press.

They also believed:

Violence could provoke stricter laws protecting slavery

Escalation might lead to civil disorder in Northern cities

Moral persuasion and political pressure remained more effective for national change

Despite these reservations, moderates often admired the courage of militant figures while rejecting their methods.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one way in which abolitionists used moral arguments to challenge the institution of slavery in the mid-nineteenth century. Explain why this approach was significant.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid moral argument (e.g., slavery as a sin, violation of natural rights, contradiction of Christian teachings).

1 mark for explaining how the argument challenged the legitimacy of slavery (e.g., framing slavery as incompatible with American ideals).

1 mark for explaining the wider significance (e.g., helped build Northern support, shaped public discourse, strengthened abolitionist credibility).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

To what extent did resistance and the use of violence contribute to the visibility and impact of the abolitionist movement in the years before the Civil War?

Mark scheme:

1 mark for describing forms of resistance by enslaved people (e.g., Underground Railroad, everyday resistance).

1 mark for linking these acts to increased visibility of the movement.

1 mark for describing the role of militant abolitionists (e.g., John Brown, use of armed resistance).

1 mark for explaining how violence intensified national debate or sectional tensions.

1 mark for evaluating the relative importance of resistance or violence compared with nonviolent moral and political efforts.

1 mark for providing a balanced, historically accurate judgement about “the extent” to which these factors shaped the movement’s impact.