AP Syllabus focus:

‘Northern manufacturing relied on free labor, while the South depended on enslaved labor; many feared slavery would undermine free labor, fueling the free-soil movement.’

Northern free labor and Southern slave labor formed sharply contrasting economic systems that shaped regional identities, influenced migration and politics, and deepened sectional tensions in the mid-19th century United States.

Economic Foundations of Free Labor in the North

Northern society increasingly relied on free labor, meaning wage-earning workers who sold their labor voluntarily in a competitive market. Industrialization expanded rapidly from the 1820s onward, creating new factories, transportation networks, and urban centers.

This photograph shows a woman textile worker in a Lowell mill, illustrating the mechanized industrial workplace that relied on Northern free wage labor. Her position among rows of spinning machines reflects the opportunities and pressures of industrial employment. The image contains no extra labels, making it a clear representation of Northern manufacturing conditions. Source.

This economic transformation depended on the belief that workers could improve their social and economic condition through discipline, education, and mobility.

Free Labor: A system in which workers enter into employment voluntarily, are paid wages, and possess the legal right to change employers.

Northern manufacturers, merchants, and artisans argued that this system produced economic dynamism, innovation, and a more egalitarian social order than systems based on coerced labor. Immigration from Ireland and Germany supplied additional labor to mills, railroads, shipyards, and construction sites, further supporting industrial growth. While inequality persisted, the ideology of free labor emphasized opportunity and self-improvement.

Northern economic development also depended on emerging market structures, including banking institutions, corporate investment, and mechanized production. These systems rewarded productivity and efficiency, reinforcing the belief that free labor was both morally superior and economically indispensable.

Southern Slave Labor and the Plantation Economy

In contrast, the South anchored its economy to slave labor, which planters claimed ensured agricultural stability and social order. Enslaved people performed nearly all labor associated with large-scale cotton production, as well as significant portions of rice, tobacco, and sugar cultivation.

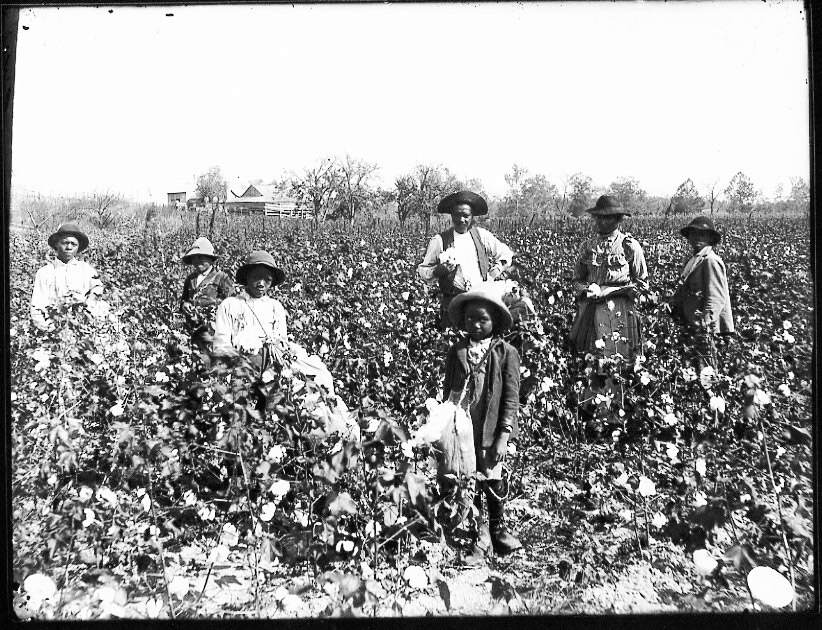

This photograph depicts a Black cotton-farming family engaged in labor-intensive fieldwork, visually conveying the demanding agricultural system long sustained by enslaved labor. Although taken after emancipation, the physical organization of work resembles earlier plantation practices. The post-war context is additional detail not required by the syllabus. Source.

This labor system generated immense profits for slaveholders, especially as global demand for cotton surged in the mid-19th century.

Slave Labor: A coerced labor system in which individuals are legally considered property and forced to work without wages or freedom of movement.

The plantation system required strict control, surveillance, and violence to maintain productivity. Wealth became concentrated among a small elite of large slaveholders, producing a region characterized by economic stratification, a limited commercial sector, and fewer urban centers. Southern leaders defended slavery as a positive good, arguing that enslaved people were cared for and that the system prevented class conflict.

Between these two regional systems, a normal sentence must appear to maintain clarity before continuing with further structured analysis.

Ideological Conflict: Competing Visions of Labor and Society

The divide between free and slave labor represented more than economic difference—it reflected contrasting ideologies about work, opportunity, and human rights. Northerners viewed free labor as essential to republican citizenship, arguing that economic independence enabled political independence. Southerners countered that slavery preserved liberty for white citizens by shielding them from menial labor.

Political debates intensified as both regions sought to extend their labor systems into the western territories. Many Northerners feared that the expansion of slavery would devalue free labor by allowing wealthy planters to dominate land and markets. This concern helped give rise to the free-soil movement, which opposed the expansion of slavery not primarily on moral grounds, but to protect opportunities for white free laborers.

Economic Regional Differences and Their National Impact

Several key features distinguished Northern and Southern economies:

Labor Structure

North: Wage labor, open labor markets, worker mobility

South: Coerced labor, plantation dominance, limited mobility and diversification

Industrialization

North: Rapid industrial growth supported by factories, railroads, banking, and technological innovation

South: Slow industrial development due to the profitability of cotton monoculture and entrenched planter interests

Urbanization

North: Expanding urban centers, immigration hubs, and diversified economies

South: Smaller cities, agricultural landscapes, and limited manufacturing infrastructure

Social Organization

North: Growing middle class, wage-earning workforce, and diverse ethnic communities

South: Rigid racial hierarchy and concentration of wealth among slaveholders

These differences affected federal policy debates on tariffs, banks, transportation improvements, and land distribution. Northern industries often supported protective tariffs, while Southern agricultural interests opposed them, fearing retaliation from foreign cotton buyers.

Free Labor, Slave Labor, and the Politics of Western Expansion

The question of how new territories would organize their labor systems brought regional tensions to the forefront. Northerners argued that slavery’s expansion would deter small farmers, suppress wages, and entrench oligarchic political structures. Southern leaders insisted that restricting slavery violated property rights and threatened their economic survival.

As political battles intensified in Congress over the future of the territories, disagreements about labor became inseparable from debates about states’ rights, national power, and the future of the Union.

The Free-Soil Movement and Growing Sectionalism

The free-soil movement played a central role in translating labor debates into political action. Supporters argued that stopping the spread of slavery would protect the dignity and economic prospects of white laborers. This ideology laid groundwork for the formation of the Republican Party, which promoted free labor as essential to national progress.

Although the free-soil position did not initially call for abolition in the South, its insistence on limiting slavery challenged the political power of slaveholders. This contributed to rising sectionalism and helped destabilize the existing national party system.

Economic Rivalry and the Approach of Civil War

By the mid-19th century, the contrast between Northern free labor and Southern slave labor had become one of the most significant sources of national conflict. Each region believed its system represented the economic future of the United States. The struggle over which labor system would dominate the expanding nation intensified political polarization, contributed to party realignment, and played a substantial role in the mounting tensions that would eventually lead to the Civil War.

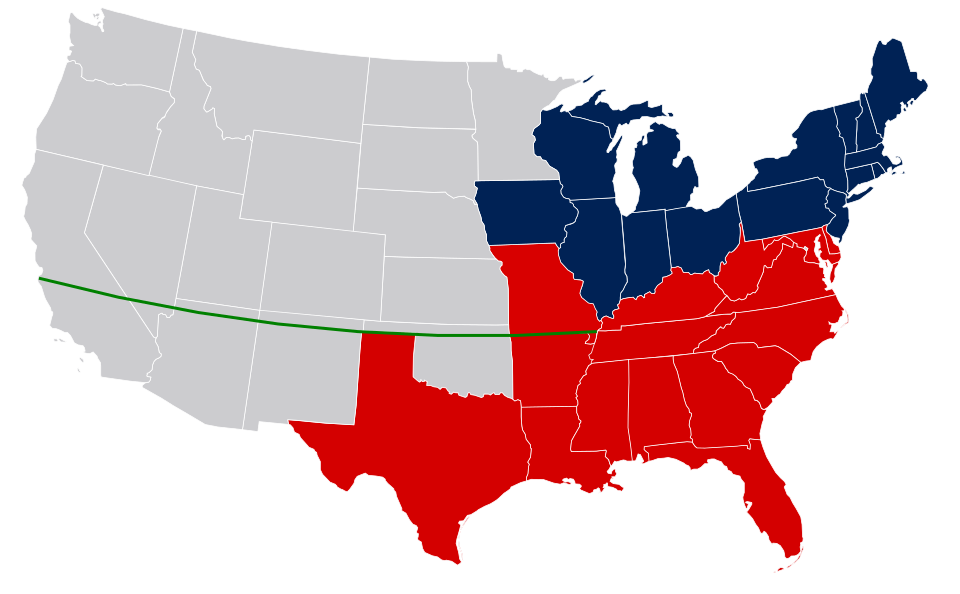

This map illustrates the geographic division between free states and slave states around 1850, including the Missouri Compromise line that shaped debates about slavery’s expansion. It visually connects economic labor systems to territorial boundaries. The map includes border states and territories, providing helpful contextual detail slightly beyond the syllabus. Source.

FAQ

Free labour ideology promoted the belief that workers could advance through discipline, education, and hard work. This created cultural expectations that individuals should strive for upward mobility.

Northern communities often developed:

Apprenticeship systems

Night schools and literacy programmes

Voluntary associations promoting temperance, thrift, and self-improvement

These institutions reinforced the idea that economic independence was central to social respectability and civic participation.

Southern slaveholders believed the plantation system maximised stability and profit by concentrating land, labour, and capital in the hands of a disciplined managerial class.

They claimed that:

Slave labour ensured predictable output

Cotton’s global demand guaranteed high returns

A non-industrial economy avoided disruptive class conflict

These arguments framed slavery as not only profitable but socially protective, even as the system limited innovation and economic diversification.

High levels of immigration supported Northern labour markets, especially in manufacturing, shipping, and infrastructure construction.

Immigrant workers reinforced free labour ideology because:

They demonstrated that newcomers could find paid work

Their employment helped expand industries and urban centres

Political leaders used immigrant success stories to justify wage-based economic systems

At the same time, competition for jobs sometimes created tension, highlighting the limits of free labour’s promise.

Both regions viewed the West as the future foundation of their labour systems. Competition was not only ideological but also practical.

Key points include:

Slaveholders feared that restricting slavery in the West would diminish political power

Northerners feared that slavery’s expansion would monopolise fertile land

Small farmers argued that plantation expansion distorted land prices and access

Thus, western settlement became a proxy battle for economic and political dominance.

Northern free labour supported sustained urban growth because industries attracted wage workers, immigrants, and entrepreneurs.

Northern cities grew due to:

Factory clusters

Expanding rail networks

Commercial banking and financial services

In the South, cities grew slowly because plantation owners invested capital in land and enslaved labour rather than urban infrastructure. As a result, urban centres remained smaller, less diversified, and less influential in regional economic planning.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the economic system of free labour in the North differed from the slave labour system in the South during the mid-nineteenth century.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks.

1 mark: Identifies a valid difference (e.g., Northern labour was wage-based, Southern labour was coerced).

2 marks: Provides a simple explanation of how this difference shaped each region’s economy or society.

3 marks: Provides a clear and accurate explanation linking the economic system to wider regional development (e.g., Northern industrialisation vs. Southern plantation agriculture).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which fears that slavery would undermine free labour contributed to the rise of the Free-Soil movement in the 1840s and 1850s.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks.

1–2 marks: Identifies that fears about slavery’s expansion affected Northern economic or political views.

3–4 marks: Explains how concerns about competition between slave labour and free labour fuelled Free-Soil beliefs (e.g., the idea that slavery would suppress wages or limit opportunities for white farmers).

5–6 marks: Provides a well-developed analysis showing the extent of this influence, possibly noting additional factors (e.g., racism, political rivalry, or sectional tensions) while still connecting them to the central issue. Answers may reference the economic, political, or ideological dimensions of Free-Soil support.