AP Syllabus focus:

‘Large-scale industrial production, technological change, pro-growth policies, and new markets generated rapid economic development and business consolidation.’

Industrial capitalism expanded rapidly after the Civil War as new technologies, supportive government policies, and expanding domestic and international markets transformed production, distribution systems, and corporate organization across the United States.

Technological Drivers of Industrial Expansion

Mechanization and Mass Production

The late nineteenth century witnessed dramatic advances in industrial technology, enabling businesses to scale production at unprecedented levels. Innovations such as the Bessemer steel process, improved steam engines, and automated machinery allowed factories to produce goods more quickly, cheaply, and reliably.

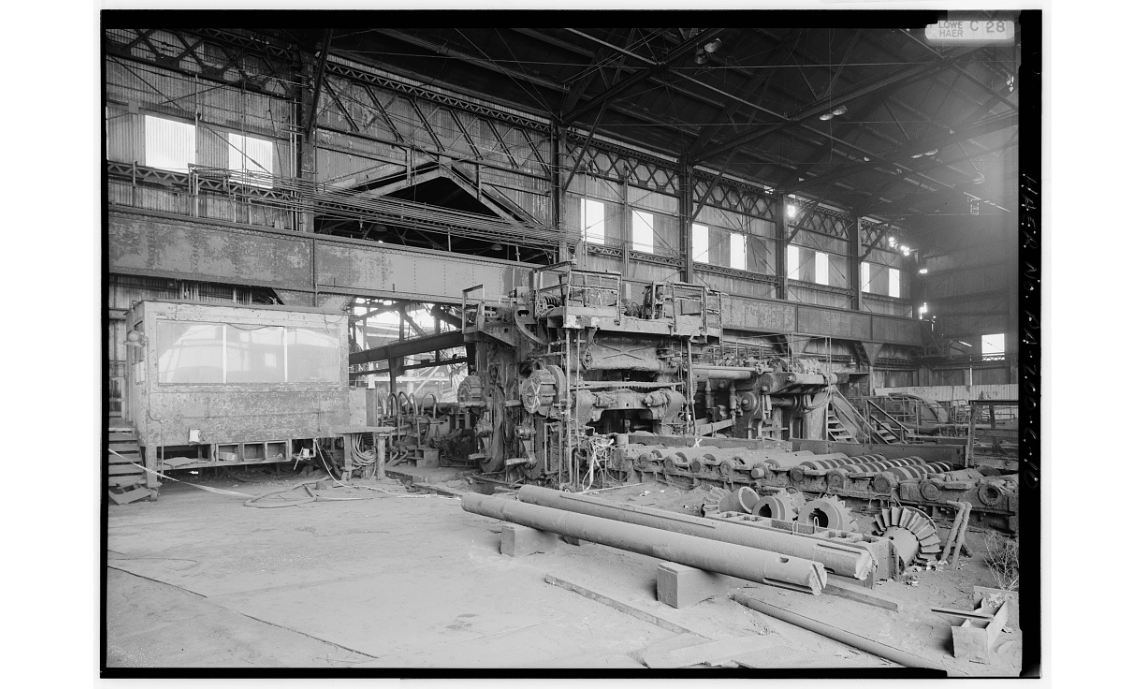

Interior photograph of the 48-inch plate mill at U.S. Steel’s Homestead Works, showing the operator’s pulpit, mill stand, and pinion stand in a mechanized rolling line. The large machinery demonstrates how industrial technology enabled continuous, high-volume steel production essential for national infrastructure. Some additional engineering details visible extend beyond the syllabus but remain helpful for visualizing large-scale mechanized industry. Source.

These technologies both reduced labor costs and standardized production.

Mechanization, a technological system that substitutes machines for human labor in manufacturing, fundamentally reshaped how goods were produced.

Mechanization: The use of machinery to increase production speed, reduce labor input, and achieve uniform output in manufacturing.

As industries adopted mechanization, productivity soared, fueling rapid economic growth. For example, steel and oil companies expanded vertically and horizontally to exploit the full benefits of technological advances.

Electric Power and Industrial Efficiency

The spread of electrical power in the 1880s and 1890s enabled factories to centralize energy systems and increase efficiency. Electricity provided more reliable power than water or steam, reduced operating costs, and allowed factories to run more machines simultaneously.

Transportation and Communication Technologies

Industrial expansion depended on the ability to move goods and information rapidly.

Key innovations included:

Transcontinental railroads, which linked distant regions into a national market

Refrigerated railcars, which enabled the shipment of perishable goods

Telegraph and telephone networks, which coordinated production, supply chains, and financial transactions

These technologies created a more interconnected economy, lowering transaction costs and enabling businesses to grow in scale and complexity.

Map illustrating the full route of the First Transcontinental Railroad from Omaha to Sacramento, with distinct color-coded segments for different rail companies. It demonstrates how a continuous rail line linked eastern manufacturing centers to western resources and markets, promoting national integration and rapid industrial expansion. Minor additional geographic details exceed syllabus requirements but reinforce spatial understanding. Source.

Government Policies Supporting Industrial Growth

Laissez-Faire Principles with Strategic Intervention

Although policymakers often championed laissez-faire principles—arguing that minimal government interference promoted competition—the federal government actively supported industrial expansion through selective interventions.

Key pro-growth policies included:

Protective tariffs, which shielded U.S. manufacturers from foreign competition

Land grants to railroads, which reduced transportation costs and opened new markets

Limited regulation, allowing large corporations to consolidate power

Laissez-faire: An economic philosophy advocating minimal government intervention in business, based on the belief that free markets promote efficiency and growth.

Despite rhetoric about free markets, government action consistently favored industrialists, creating conditions for large-scale business consolidation.

Legal and Judicial Support

Courts often interpreted the Constitution in ways that favored business interests.

The Fourteenth Amendment was frequently invoked by corporations claiming “personhood,” protecting them from certain state regulations.

Antitrust enforcement remained weak until the early twentieth century, enabling trusts and holding companies to flourish.

These legal frameworks reduced uncertainty for investors and encouraged aggressive business expansion.

Expanding Markets and the Rise of National Corporations

National Markets and Standardized Goods

By linking producers and consumers across vast distances, improved transportation and communication systems created a national market, transforming regional producers into national corporations. Businesses could sell standardized goods to millions of consumers, increasing economies of scale.

The emergence of national brands, mail-order companies like Sears, Roebuck, and the rise of department stores reflected this massive consumer integration.

Urbanization and Consumer Demand

Urban growth contributed significantly to industrial expansion. Cities offered:

Large, concentrated markets for manufactured goods

Access to immigrant and internal migrant labor

Infrastructure supporting large-scale production and distribution

As more Americans lived in cities, demand for manufactured products grew, encouraging additional industrial investment.

International Markets and Resource Acquisition

Industrialists increasingly looked overseas for both consumers and raw materials.

The United States exported agricultural and industrial goods to Europe, Latin America, and Asia.

Overseas trade encouraged further industrial development at home.

Companies sought new sources of rubber, oil, metals, and other materials essential to industrial processes.

This outward expansion supported business consolidation as firms competed globally.

Business Consolidation and Corporate Growth

Large-Scale Production and Corporate Structures

Industrial capitalism expanded not only because of output increases but also because of new management structures that allowed firms to operate at massive scale.

Corporations adopted:

Professional managerial hierarchies

Standardized accounting

Coordinated national distribution networks

These innovations enabled companies to control production from raw materials to final sale.

Trusts and Holding Companies

To stabilize prices, reduce competition, and maximize profits, business leaders created trusts, which combined multiple firms under a single board, and later holding companies, which legally controlled other corporations. These mechanisms concentrated wealth and market power, reflecting the consolidation central to industrial capitalism’s rapid growth.

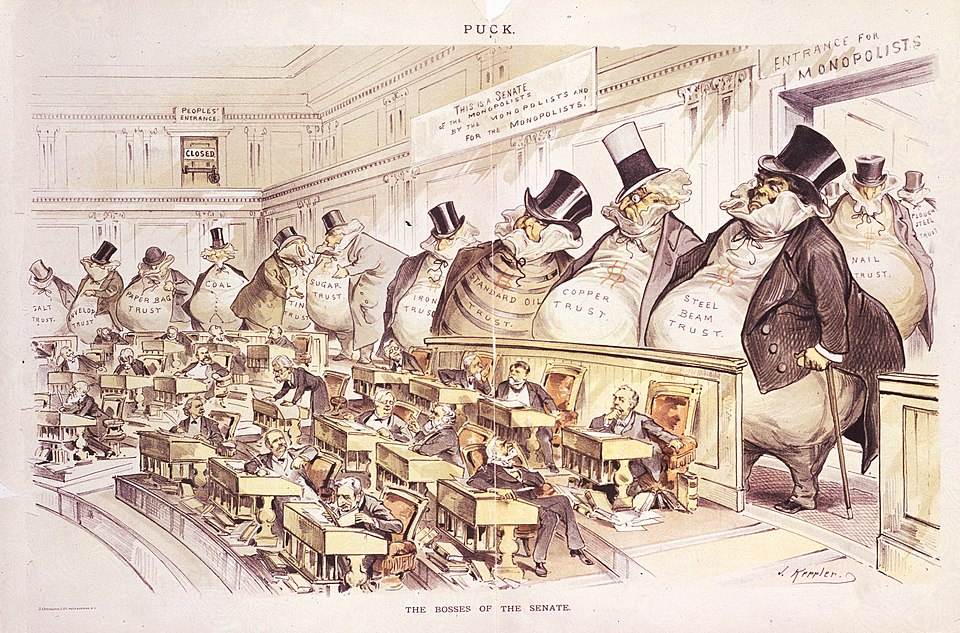

Joseph Keppler’s famous cartoon depicts corporate trusts as oversized money-bag figures dominating the Senate chamber, symbolizing the political influence of concentrated industrial wealth. The barred “People’s Entrance” highlights concerns about diminished democratic access during the Gilded Age. Though the cartoon also reflects broader antitrust debates beyond the immediate subtopic, it vividly illustrates public anxieties about business consolidation. Source.

Capital Investment and Financial Markets

Industrial expansion required enormous capital. Banks, investment houses, and stock markets provided financing for railroads, steel mills, and oil refineries. The growth of national financial institutions further accelerated industrial development and supported the rise of corporate giants.

Interconnected Forces Driving Expansion

Industrial capitalism expanded because technology, policy, and markets reinforced one another.

Technological innovation increased production and lowered costs.

Government policy favored industrial growth and protected large businesses.

Expanding domestic and international markets created unprecedented demand.

These forces collectively produced the rapid economic development and business consolidation emphasized in the AP U.S. History specification.

FAQ

New management systems allowed firms to coordinate operations across multiple sites, ensuring greater efficiency and consistency.

Corporations adopted practices such as departmental oversight, cost accounting, and centralised decision-making, which reduced waste and improved productivity.

These innovations enabled companies to scale production rapidly because leaders could manage complex supply chains, integrate research, and standardise processes across national networks.

Industrial projects such as railroads and steel mills required unprecedented amounts of capital, attracting both domestic and international investors.

British and European financiers viewed American infrastructure and manufacturing as high-return opportunities, directing significant funds into railway bonds, industrial stocks, and expansion loans.

This influx of capital helped fuel corporate consolidation by enabling large firms to buy competitors, invest in technology, and expand into new markets.

National markets encouraged producers to develop standardised goods that could be distributed and sold widely, reducing reliance on local buyers.

Retailers increasingly depended on predictable, mass-produced products that could be shipped efficiently via rail.

As catalogue companies and department stores grew, producers gained access to millions of consumers, shifting power away from small local retailers and towards large-scale distributors.

Mechanisation reduced the need for skilled artisanal labour but dramatically increased the demand for semi-skilled and unskilled workers who could operate machinery.

Industries such as steel, oil, and meatpacking relied on repetitive, machine-assisted tasks that required minimal training.

This restructuring of labour demand helped firms expand quickly, as workers could be hired and trained rapidly to meet rising production targets.

Vertical integration allowed firms to control every stage of production, from raw materials to distribution, reducing dependency on external suppliers and stabilising costs.

Horizontal integration, by contrast, involved merging with or buying out competitors to control market share and reduce price volatility.

Together, these strategies helped corporations grow large enough to dominate markets, achieve cost efficiencies, and respond more effectively to national and international competition.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify and briefly explain one way in which technological innovation contributed to the expansion of industrial capitalism in the period 1865–1898.

Mark scheme (3 marks total)

1 mark for correctly identifying a relevant technological innovation (e.g., Bessemer process, telegraph, railroads, mechanised factory equipment).

1 mark for explaining how the innovation increased production, efficiency, connectivity, or market reach.

1 mark for linking the innovation to broader industrial expansion (e.g., facilitated national markets, lowered costs, encouraged business consolidation).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how government policy and expanding markets together contributed to the rapid growth of industrial capitalism in the United States between 1865 and 1898.

Mark scheme (6 marks total)

1 mark for identifying a relevant government policy (e.g., protective tariffs, land grants to railroads, limited regulation).

1 mark for explaining how this policy supported industrial growth (e.g., shielding domestic industry, reducing transport costs, enabling corporate consolidation).

1 mark for identifying a relevant development in domestic or international markets (e.g., creation of national markets through railroads, rising urban consumer demand, expansion of overseas trade).

1 mark for explaining how markets encouraged business growth (e.g., increased demand, access to resources, larger customer bases).

1 mark for analysing the interaction between policy and markets (e.g., policies enabled firms to exploit expanding markets more effectively).

1 mark for a coherent, historically supported argument showing how the combination of these factors accelerated industrial capitalism.