AP Syllabus focus:

‘Many business leaders increased profits by consolidating corporations into large trusts and holding companies, concentrating wealth further.’

Industrial consolidation accelerated during the Gilded Age as powerful business leaders organized trusts and holding companies, reshaping markets, concentrating wealth, and redefining how corporations pursued influence, efficiency, and profit.

Trusts and the Logic of Consolidation

Trusts emerged as a dominant organizational form that allowed multiple firms to act as a single coordinated entity, sharply reducing competition in key industries. Business leaders believed that eliminating destructive price wars and stabilizing markets would not only secure higher profits but also create more predictable production environments.

Trust: A legal arrangement in which several companies transfer shares to a central board of trustees, enabling unified management and reduced internal competition.

Trusts often became mechanisms through which a small number of influential industrialists—sometimes labeled captains of industry or robber barons—could shape prices, output levels, and market access. This concentration of corporate power fueled national debates over economic fairness as Americans questioned whether such arrangements undermined free-market competition.

Why Trusts Formed

Industrial leaders adopted trust structures for several interconnected reasons:

Eliminating competition that pushed prices downward and destabilized profit margins.

Achieving economies of scale, which lowered production costs by centralizing purchasing, transportation, and distribution.

Coordinating output to match demand and avoid gluts that triggered economic downturns.

Influencing policy, as larger consolidated entities wielded greater lobbying power at the state and federal levels.

These motives aligned with rapid technological changes and massive industry expansion, making consolidation an appealing strategy for maintaining dominance in an increasingly interconnected national economy.

Holding Companies and Corporate Control

While trusts provided one route to consolidation, the rise of holding companies marked an important legal innovation that enabled even tighter control over an expanding corporate empire.

Holding Company: A corporation created to own a controlling share of stock in multiple other companies, allowing centralized oversight without merging operations.

Holding companies expanded quickly after states such as New Jersey revised corporate laws in the 1880s and 1890s to permit firms to own stock in other corporations. These changes made formal consolidation easier and more legally defensible, especially as public and political scrutiny intensified around trust arrangements.

Unlike trusts, which operated through trustee-managed share transfers, holding companies offered a more durable structure because ownership and control were embedded directly in stock ownership. This form of consolidation allowed business leaders to build vast, hierarchical corporate networks that crossed state lines and incorporated dozens of previously independent enterprises.

Functions and Advantages of Holding Companies

Holding companies became critical tools for shaping Gildled Age capitalism. Their advantages included:

Centralized strategic decision-making, reducing organizational conflict among constituent firms.

Flexible acquisition of competitors, permitting step-by-step expansion without total merger.

Financial leverage, allowing parent companies to use dividends and capital markets to fuel further consolidation.

Enhanced market coordination, ensuring prices, wages, and production levels aligned across subsidiary firms.

Even as some Americans argued this represented efficient modern management, critics insisted such structures suppressed competition and threatened democratic economic opportunity.

Wealth Concentration and Corporate Power

The consolidation of corporations into trusts and holding companies dramatically concentrated wealth in the hands of a small number of industrialists. Leaders such as John D. Rockefeller in oil and J. P. Morgan in finance became emblematic of this transformation. These individuals used their organizational innovations to exert unprecedented control over vast sectors of the economy.

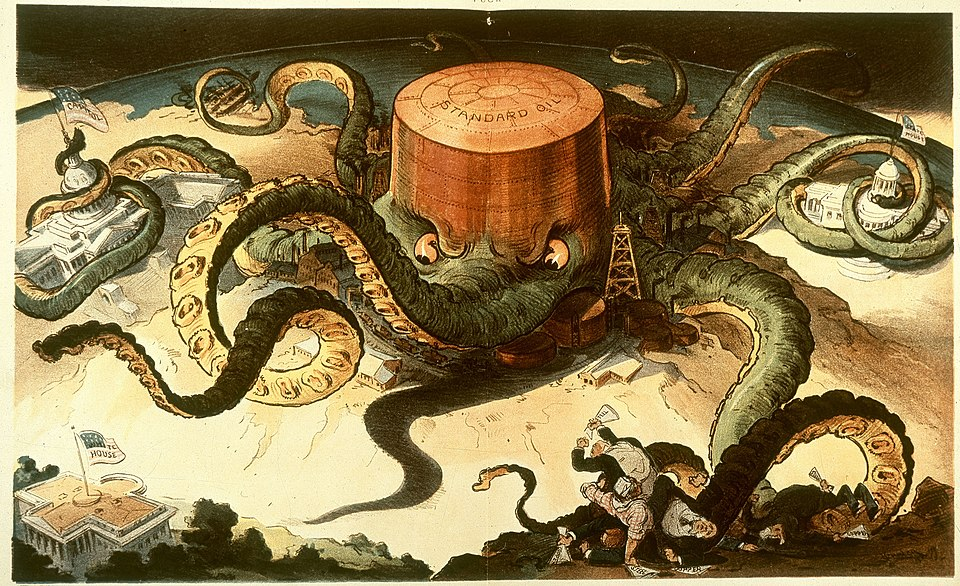

This cartoon from Puck portrays Standard Oil as a massive octopus with tentacles extending over industries, transportation networks, and government buildings, symbolizing fears of monopolistic corporate domination. Its labeled components show critics’ views of how trusts could entangle both economic and political institutions. The cartoon contains extra contextual details beyond the syllabus, such as specific buildings and sectors targeted by the octopus. Source.

Economic and Social Effects

Gilded Age consolidation produced several far-reaching consequences:

Market domination, as a few giant firms controlled large percentages of national output.

Rising inequality, with elite industrialists accumulating wealth at rates unmatched by average workers.

Reduced competition, raising fears that monopolistic pricing and exclusionary practices harmed consumers and small businesses.

Heightened regulatory pressure, prompting calls for federal oversight and contributing to legislation such as the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890).

Public reactions ranged from admiration for the era’s technological and organizational achievements to anxiety over concentrated economic power.

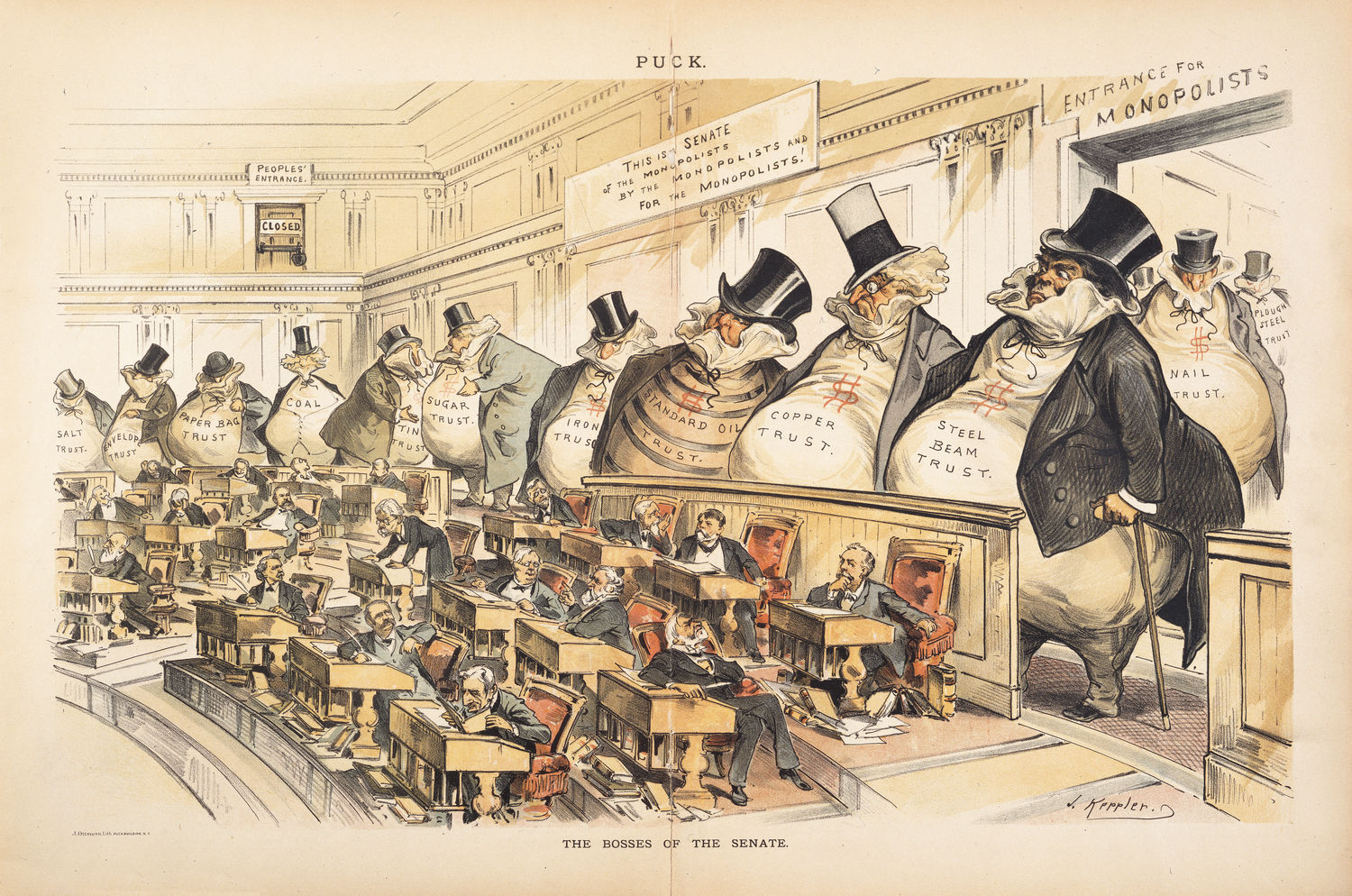

This 1889 Puck cartoon depicts corporate trusts as giant money bags overshadowing the U.S. Senate, reflecting public concerns that concentrated wealth had overtaken democratic governance. The barred “people’s entrance” illustrates how monopolists were perceived to displace citizens’ influence. The labeled money bags identify individual industries, adding minor details beyond the syllabus focus while reinforcing the theme of corporate power. Source.

Consolidation as a Defining Feature of Industrial Capitalism

By the late nineteenth century, consolidation through trusts and holding companies had become a defining engine of American industrial capitalism. These structures enabled firms to operate on unprecedented scale, shaping the national economy and influencing the relationship between corporations, workers, consumers, and policymakers. Their rise embodied both the dynamic growth and the contentious inequalities of the Gilded Age, reflecting the syllabus emphasis on how business leaders increased profits and concentrated wealth through corporate consolidation.

FAQ

Several states, most notably New Jersey in the 1880s and 1890s, rewrote incorporation laws to allow one corporation to own stock in another.

This legal shift made it far easier for large firms to consolidate competitors without relying on informal trust agreements, which were increasingly challenged in courts.

States competed to attract large corporations by offering lenient regulations, accelerating the adoption of holding-company structures nationwide.

Industrialists relied on tightly integrated organisational and financial mechanisms, including:

• Centralised boards that approved budgets, output levels, and pricing strategies.

• Cross-directorships, where the same executives sat on multiple boards.

• Control of key financing streams, ensuring subsidiaries depended on the parent company for capital allocation.

These strategies allowed leaders to maintain dominance even when subsidiaries were nominally independent.

Critics argued that trusts could manipulate supply and restrict competition, enabling them to set artificially high prices.

They also feared trusts could limit innovation by suppressing smaller firms that introduced new technologies or methods.

Some observers believed consumers faced reduced choice as markets consolidated under a handful of dominant corporations.

Industrialists framed consolidation as efficient, modern, and necessary for competing in national and international markets. They emphasised stability, predictability, and lower production costs.

Reformers responded that such justifications masked monopolistic behaviour. They argued consolidation primarily protected profits, undermined competition, and threatened democratic accountability.

Major investment banks, particularly those led by financiers like J. P. Morgan, facilitated mergers by underwriting stocks, organising buyouts, and stabilising reorganised companies.

Banks also coordinated negotiations between rival firms, smoothing the path to consolidation.

By controlling access to capital, financial institutions often determined which firms could expand, merge, or survive in competitive industries.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why many late nineteenth-century business leaders formed trusts or holding companies.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark:

• Identifies a basic reason (e.g., to reduce competition, to stabilise prices, to increase profits).

2 marks:

• Provides a more developed explanation (e.g., eliminating price wars allowed firms to maintain higher profit margins).

3 marks:

• Offers a clear, contextualised explanation linking consolidation directly to broader economic trends (e.g., rapid industrial growth, economies of scale, coordination of output, or use of such structures to dominate markets).

(4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of the period 1865–1898, evaluate the extent to which the consolidation of corporations into trusts and holding companies contributed to the concentration of wealth and economic power in the Gilded Age.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

4 marks:

• Demonstrates knowledge of trusts/holding companies and their role in the late nineteenth century.

• Provides at least one clear explanation of how consolidation increased wealth or market power.

• Some contextual references to industrialisation or leading figures (e.g., Rockefeller, Morgan).

5 marks:

• Shows a more detailed evaluation of the extent of consolidation’s impact, including multiple factors or consequences (e.g., monopolistic practices, reduced competition, influence over government, rising inequality).

• May begin to note limitations or additional influences (e.g., technology, national markets).

6 marks:

• Presents a well-reasoned, balanced evaluation with specific evidence.

• Explains how consolidation contributed to concentrated wealth and power, while also considering other forces shaping the Gilded Age economy.

• Demonstrates clear analytical judgement about the relative importance of consolidation compared to other factors.