AP Syllabus focus:

‘Redesigned financial and management structures, advances in marketing, and a growing labor force helped businesses greatly increase output.’

In the late nineteenth century, industrial corporations revolutionized American economic life by reshaping finance, management, marketing, and labor organization, enabling unprecedented growth, expanded production, and national market dominance.

Managing Big Business in the Gilded Age

Building New Financial and Management Structures

The rise of large-scale industrial corporations after the Civil War required organizational strategies far beyond those of traditional family-owned businesses. As firms grew more complex, business leaders adopted redesigned financial and management structures, enabling them to coordinate production, reduce costs, and operate across multiple regions.

Industrial titans like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller pioneered systems that separated ownership from day-to-day control, allowing corporations to operate efficiently under multi-layered hierarchies.

Vertical Integration: A business strategy in which a company controls multiple stages of production and distribution to reduce costs and increase efficiency.

Managers used systematic reporting, cost accounting, and performance tracking to oversee distant factories, rail lines, and distribution networks.

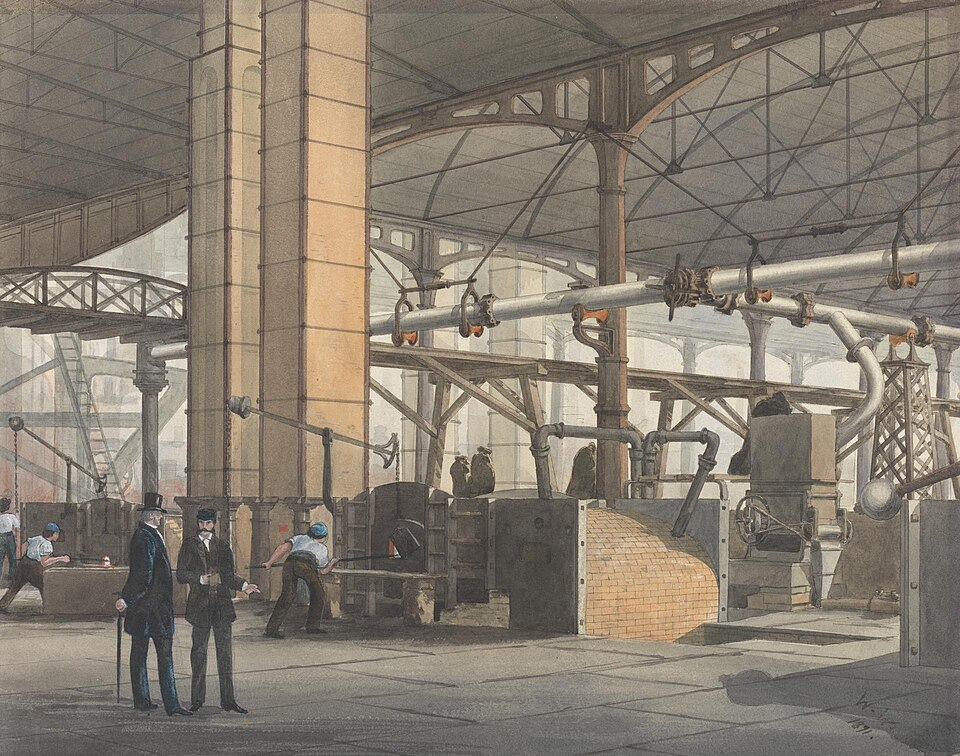

This watercolor illustrates a large industrial workspace characteristic of late nineteenth-century factories, where dense machinery and supervised labor required systematic management. Although British, it closely mirrors U.S. factory conditions during the Gilded Age, highlighting the operational scale that demanded new organizational structures. Source.

These administrative innovations reduced waste and standardized operations across the national economy.

Large firms also relied on investment banks, especially J.P. Morgan & Co., to provide capital for expansion, reorganize struggling companies, and facilitate mergers. By pooling capital from investors, banks helped corporations fund new technologies, acquire competitors, and stabilize volatile industries such as railroads.

The Middle Management Revolution

Expanding corporations created a new tier of middle managers responsible for supervising workers, enforcing standards, and coordinating communication across departments. This managerial class expanded white-collar employment opportunities and strengthened internal corporate control, making large enterprises more stable and predictable.

Middle management also connected local operations with centralized corporate leadership. As a result, firms could monitor pricing, production, and transportation more effectively, enabling consistent output and strategic market planning.

Advances in Marketing and Consumer Outreach

To sustain high production levels, businesses turned to innovative marketing techniques that reshaped American consumer culture. National companies relied on mass advertising, trademarked brands, and standardized packaging to distinguish their goods in an increasingly crowded marketplace.

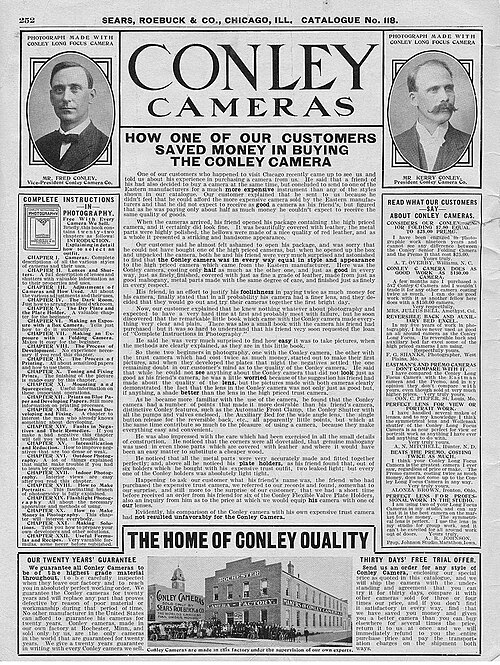

Manufacturers invested in print advertising, billboards, and magazine promotions, expanding demand and fostering brand loyalty. Mail-order companies such as Sears, Roebuck and Co. used catalogs to reach rural consumers who lacked access to urban storefronts.

Branding: The practice of creating a recognizable identity—such as a name, logo, or design—to differentiate a company’s products from competitors.

Marketing departments helped corporations gather information on consumer preferences, adjust product lines, and tailor promotional strategies to regional or national audiences. This coordinated marketing effort became essential as firms aimed to supply and shape demand in a national economy.

One important sentence here to separate definition blocks.

Economies of Scale: Cost advantages gained when increased production lowers the average cost per unit, enabling large firms to underprice smaller competitors.

Marketing innovations ultimately linked production to consumption, ensuring that factories could operate at full capacity and reinforcing the dominance of the largest corporations.

Mail-order giants like Sears, Roebuck and Co. and Montgomery Ward used thick catalogs to market everything from farm tools to household goods, allowing rural customers to order standardized products delivered by rail.

This Sears catalogue page demonstrates how national mail-order companies used detailed product descriptions and standardized pricing to reach consumers across the country. It represents the sophisticated marketing methods that supported large-scale corporate production. Although dated 1909, it reflects the same advertising strategies emerging in the late nineteenth century. Source.

A Growing Labor Force and Expanding Output

Industrial expansion depended heavily on a rapidly growing workforce, fueled by immigration, internal migration, and demographic growth. Millions of European immigrants supplied labor for factories, steel mills, and railroads, while rural Americans moved to cities seeking wage work.

The availability of abundant labor allowed corporations to increase output dramatically while keeping wages relatively low. Management often divided tasks into simple, repetitive steps, reducing the need for skilled labor and increasing supervisory control over production.

Workforce Organization and Corporate Labor Policies

To manage this expanding workforce, corporations developed new administrative strategies. Foremen and supervisors enforced strict productivity targets, while time-discipline practices—such as fixed schedules, timed breaks, and production quotas—regulated daily labor.

Many employers adopted welfare capitalism measures, including company housing or recreational facilities, to promote worker loyalty and reduce turnover. However, such programs also reinforced managerial authority and discouraged labor activism.

Corporate leaders insisted that workplace discipline and centralized control were necessary to maintain efficiency in mass production industries. This belief shaped hiring practices, workplace rules, and managerial oversight throughout the Gilded Age.

Families sometimes sent multiple members—including women and older children—into wage labor to cope with low pay and irregular employment.

This photograph shows a crowded spinning room where children and adults work side by side, reflecting the expanding industrial labor force that powered large corporate enterprises. It highlights how entire families contributed to factory production. The emphasis on child workers extends slightly beyond this subtopic but reinforces the pressures that shaped labor management in the Gilded Age. Source.

Finance, Marketing, and Labor as Pillars of Corporate Growth

Together, redesigned financial systems, sophisticated marketing strategies, and a large, adaptable workforce enabled American businesses to greatly increase output. These developments supported the emergence of powerful corporations capable of dominating national markets, driving economic growth, and reshaping American society during the Gilded Age.

FAQ

Corporations began using uniform accounting systems that enabled managers to compare costs across departments, factories, and regions. This allowed leaders to identify waste, streamline production, and set output targets based on measurable data rather than local judgement.

These accounting tools also helped managers justify investments, mergers, and price changes to shareholders, making decision-making more predictable and financially oriented.

By the 1890s, specialised advertising agencies emerged to design campaigns, purchase national newspaper space, and standardise brand messaging. Their work ensured that products reached consumers across the entire country with consistent imagery and slogans.

Agencies also conducted early market research, helping corporations adjust strategies based on consumer responses and regional sales trends.

Trademarks helped companies protect their products from imitation, especially as mass production flooded markets with similar goods. A recognisable brand reassured consumers that a product’s quality would be consistent no matter where it was purchased.

Branding also allowed companies to charge premium prices, as consumers associated logos and slogans with reliability and modernity.

Large firms established recruitment offices in major cities, ports, and industrial centres to secure a steady flow of workers. They often targeted recent immigrants, offering low wages but promising stable employment.

Some companies partnered with labour agents who travelled abroad to advertise opportunities, helping build ethnically concentrated workforces in mines, mills, and factories.

Corporations relied heavily on telegraph lines, written reports, and standardised forms to maintain oversight of distant facilities. These methods allowed headquarters to receive daily or weekly data on production, materials, and staffing.

Many firms also introduced company rulebooks that unified expectations across all locations, ensuring consistent procedures and discipline.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which redesigned financial or management structures contributed to the growth of large industrial corporations in the late nineteenth century.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying a valid structural change (e.g., introduction of hierarchical management, reliance on investment banks, use of cost accounting).

• 1 mark for describing how this change functioned (e.g., coordination across multiple production sites, access to capital for expansion).

• 1 mark for explaining why this contributed to corporate growth (e.g., increased efficiency, ability to outcompete smaller firms, stabilisation of large enterprises).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which advances in marketing transformed the relationship between large businesses and consumers during the Gilded Age.

Mark scheme:

• Up to 2 marks for describing specific marketing developments (e.g., national advertising, branding, mail-order catalogues, standardised packaging).

• Up to 2 marks for analysing how these innovations reshaped consumer access or behaviour (e.g., expansion of national markets, creation of brand loyalty, increased demand for mass-produced goods).

• Up to 2 marks for providing a supported judgement on the extent of transformation (e.g., significant impact due to national reach, but limited by continued regional differences or uneven consumer access).