AP Syllabus focus:

‘Businesses increasingly sought markets and natural resources outside the United States, expanding influence in the Pacific Rim, Asia, and Latin America.’

The late nineteenth century saw U.S. businesses expand beyond national borders, pursuing overseas markets, raw materials, and investment opportunities that reshaped global economic relationships.

Expanding U.S. Commercial Influence Abroad

Growing industrial output pushed American firms to look overseas for both consumers and resources. This outward economic reach became a defining feature of Gilded Age capitalism.

Motivations for Overseas Expansion

U.S. entrepreneurs increasingly turned to the Pacific Rim, Asia, and Latin America to sustain rapid industrial growth.

Key motivations included:

Seeking new markets for surplus manufactured goods.

Acquiring natural resources such as sugar, rubber, and minerals.

Competing with European empires for global commercial presence.

Reducing dependence on cyclical domestic markets and financial instability.

Many leaders believed that international commerce would stabilize the economy and strengthen national power. This belief aligned with a broader cultural confidence in American industrial superiority.

Pacific Rim: Trade Routes and Strategic Access

U.S. business expansion in the Pacific Rim reflected both economic ambition and strategic interest in transoceanic commerce. Firms hoped to tap into growing Asian markets, particularly China and Japan, where Western nations were already competing for access to trade.

Pacific Rim: The region of countries and territories bordering the Pacific Ocean, significant in global commerce for its strategic ports and emerging markets.

American merchants pressed for improved shipping networks, coaling stations, and commercial treaties to facilitate exchange. This expansion aligned with the belief that access to Asian markets would help absorb America’s growing industrial output. Business leaders and policymakers increasingly framed commercial access as essential to national prosperity.

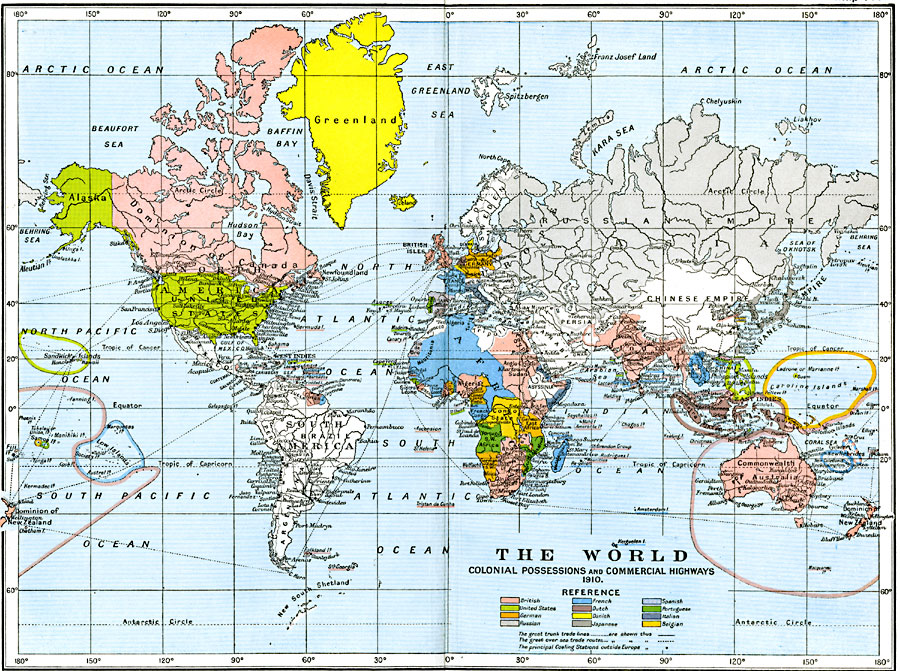

American business leaders increasingly imagined the globe as a network of commercial highways that steamships and railroads could use to carry U.S. goods to distant markets.

World map from 1910 showing colonial possessions and the principal sea and rail “commercial highways.” The shaded areas mark European and U.S. empires, while the lines trace major trade routes and coaling stations that steamships depended on. The map includes colonial territories and routes beyond those controlled by the United States, so students should focus on how it situates U.S. expansion within a broader world system of imperial trade. Source.

China and the Pursuit of Market Access

China represented a lucrative target for U.S. manufacturers seeking millions of potential consumers. Although the Open Door Outlook had not yet fully taken shape in this period, American businessmen already supported policies that would prevent European powers from excluding U.S. trade.

They favored:

Equal commercial opportunities in treaty ports.

Low tariff barriers for U.S. goods.

Diplomatic efforts to limit exclusive European spheres of influence.

American companies positioned themselves as advocates of free trade, hoping this philosophy would secure long-term access to Chinese markets.

Japan and Expanding Commercial Exchange

Japan’s rapid industrialization following the Meiji Restoration opened new opportunities for American exports. Businesses promoted bilateral trade relationships that emphasized the exchange of machinery, textiles, and manufactured goods.

Commercial relationships benefited from:

Expanding steamship routes.

Improved communication networks.

Growing Japanese interest in Western industrial expertise.

These exchanges demonstrated how technological change created deeper international connections that extended beyond simple resource extraction.

Latin America and U.S. Corporate Investment

In Latin America, U.S. railroad companies, mining ventures, and agricultural firms made significant investments that transformed local economies. American businesses used capital and technology to shape development patterns while securing access to raw materials.

Major areas of U.S. economic activity included:

Railroad construction, which facilitated commodity export flows.

Plantation agriculture, especially in sugar-producing regions.

Mining, where American firms extracted copper, silver, and other minerals.

Banking and finance, which tied Latin American markets to U.S. capital.

These investments extended American economic influence even when political control remained local.

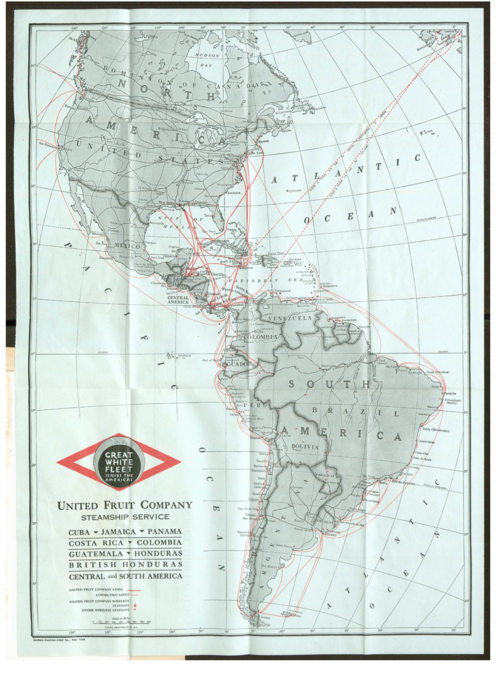

Companies such as the United Fruit Company invested in railroads, ports, and plantations across Central America and the Caribbean to secure tropical commodities and ship them efficiently to U.S. consumers.

Map produced by the United Fruit Company in 1924 showing its steamship routes linking U.S. Gulf and Atlantic ports with Central America and the Caribbean. The dense web of lines reveals how a single U.S. corporation controlled key corridors for the banana trade and other agricultural exports. Because the map dates slightly after 1898 and includes some later routes and ports, it goes beyond the exact AP Period 6 timeframe but still illustrates the long-term pattern of corporate influence in Latin America. Source.

Central America and the Caribbean: Resource Extraction and Market Integration

U.S. companies became deeply involved in Central American and Caribbean economies. Firms such as fruit exporters integrated transportation networks, ports, and farm operations to create vertically organized international businesses. This commercial dominance shaped local labor systems and linked regional production to U.S. consumer markets.

Vertical integration: A business strategy in which a company controls multiple stages of production and distribution, reducing costs and increasing efficiency.

Such control gave U.S. businesses significant leverage over local governments and trade policies. Economic ties reinforced political relationships that would become even more pronounced in the twentieth century.

South America and Expanding Industrial Markets

Although European powers had long dominated South American commerce, American manufacturers gradually gained ground by exporting machinery, textiles, and processed goods. Improved shipping and telegraph connections helped integrate South American ports into broader U.S. trade networks.

American business leaders believed these relationships would secure reliable outlets for industrial output, helping reduce domestic market volatility. Growing economic influence reinforced national arguments for a more assertive diplomatic presence in the Western Hemisphere.

Communications, Transportation, and Global Reach

Advances in international communication networks, including telegraph cables and steam-powered shipping, allowed U.S. companies to manage operations across vast distances. Businesses could more easily coordinate production, shipping schedules, and financial transactions, making overseas investment less risky.

As a result, economic expansion abroad became an increasingly normal feature of American industrial strategy rather than an exceptional one. Strengthened global connections reinforced the idea that prosperity depended on both domestic and foreign markets.

Business Pressure and Government Support

Although the United States did not yet pursue formal imperialism on a large scale, business interests frequently encouraged federal officials to protect commercial access. Diplomatic missions, trade agreements, and occasional military involvement often supported U.S. economic objectives.

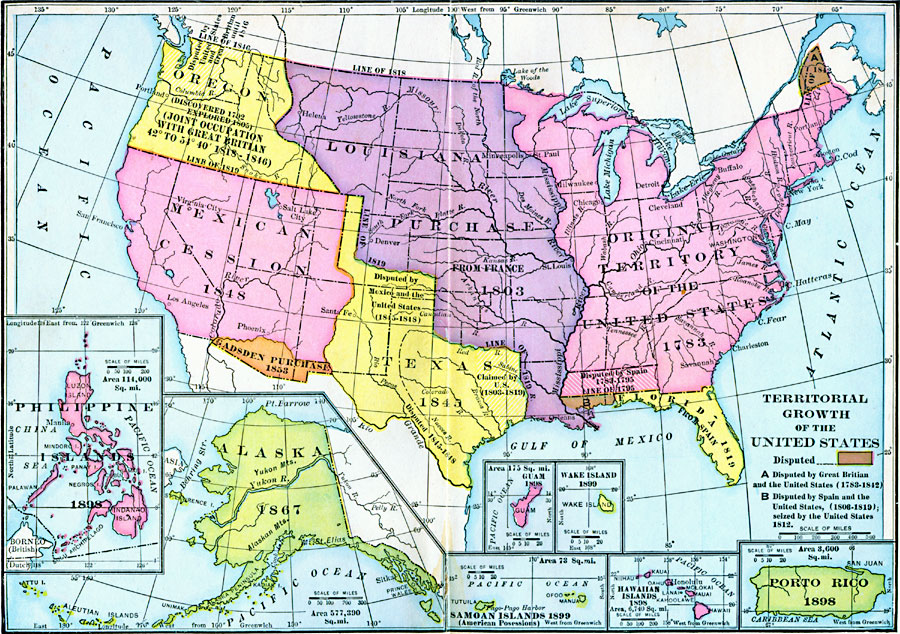

By 1900, the United States held island territories from the Caribbean to the central Pacific—Puerto Rico, Guam, Hawaii, the Philippines, Samoa, and small Pacific islands—that anchored trade and investment in Latin American and Asian markets.

Map showing the territorial growth of the United States from 1783 to 1900, with late-nineteenth-century acquisitions such as Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, the Philippines, Wake Island, and American Samoa clearly labeled. These new possessions created a chain of bases and coaling stations that supported commercial expansion into the Pacific, Asia, and Latin America. The map also portrays earlier continental acquisitions that predate AP Period 6 and are not the primary focus of this subtopic. Source.

FAQ

Steam-powered vessels reduced travel time, increased cargo capacity, and enabled predictable shipping schedules essential for long-distance trade.

These developments allowed American firms to coordinate supply chains more efficiently and reach remote ports in Asia and Latin America with less risk.

Coaling stations, often located on island territories, became crucial logistical assets that enabled continuous travel across the Pacific.

Large firms regularly lobbied federal officials to protect commercial access and negotiate favourable trade agreements.

Their influence encouraged diplomats to prioritise open markets, reduced tariffs, and policies preventing European powers from establishing exclusive spheres of influence.

Corporations also supplied information about regional resources, labour conditions, and infrastructure needs, indirectly guiding U.S. strategic interests.

In Asia, the United States pursued access to established markets, focusing on treaty port entry, shipping rights, and competitive positioning against European powers.

In Latin America, American companies invested more directly through railways, plantations, and banking institutions, embedding U.S. interests within local economies.

The contrast lay between market access in Asia and deeper structural economic involvement in Latin America.

Island territories offered strategic points for refuelling steamships, storing goods, and establishing communication links.

They acted as staging grounds for trade with Asia and Latin America, helping American companies maintain reliable transport routes.

Businesses viewed these territories as economic assets that reduced costs and increased the efficiency of transoceanic commerce.

American firms introduced vertically integrated operations that reorganised local labour around plantation and export-oriented industries.

This often meant:

Seasonal or permanent wage labour replacing subsistence farming

Increased dependence on single-crop economies

Labour migration to company-controlled railways, ports, and farms

Such changes strengthened corporate influence while weakening traditional economic practices.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify and briefly explain one reason why late nineteenth-century U.S. businesses sought to expand their influence into the Pacific, Asia, or Latin America.

Mark Scheme

• 1 mark for correctly identifying a valid reason (e.g., desire for new markets, access to natural resources, competition with European powers, need for coaling stations).

• 1 mark for a brief explanation showing understanding of how the reason encouraged overseas expansion (e.g., surplus industrial goods required foreign consumers).

• 1 additional mark for contextual accuracy or specificity (e.g., mention of steamship routes, commercial treaties, or corporate investment such as the United Fruit Company).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse the extent to which economic interests shaped U.S. involvement in the Pacific and Latin America between 1865 and 1898.

Mark Scheme

• Up to 2 marks for identifying relevant economic interests (e.g., securing raw materials, expanding export markets, establishing trade routes, gaining access to Asian ports).

• Up to 2 marks for explaining how these interests influenced U.S. actions (e.g., pursuit of commercial treaties in Asia, investment in railways and plantations in Latin America, acquisition of island territories for coaling stations).

• Up to 1 mark for providing specific and accurate examples (e.g., growth of U.S. shipping networks; activities of large corporations such as the United Fruit Company; interest in Chinese markets).

• Up to 1 mark for analysis that evaluates the extent of economic influence (e.g., acknowledging the interplay between economic motives and strategic or political pressures).