AP Syllabus focus:

‘Asian American activists organized to confront discrimination, build community institutions, and claim greater social and economic equality.’

Introduction

Asian American movements in the 1960s and 1970s mobilized diverse communities to challenge discrimination, strengthen local institutions, and demand political, social, and economic empowerment.

The Emergence of a Pan–Asian American Identity

The rise of Asian American activism drew from shared experiences of exclusion, racial violence, and legal discrimination that had long shaped the lives of Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, Korean, and South Asian Americans. A central development of this period was the construction of a pan–Asian American identity, which linked previously separate ethnic communities.

Pan–Asian American identity: A political and cultural framework that emphasized unity among diverse Asian ethnic groups to confront racism and advocate for collective rights.

Student organizations were essential in crafting this identity. Influenced by the New Left and the broader Civil Rights Movement, young activists argued that Asian Americans faced structural inequality similar to other marginalized groups. This framing helped shift public understanding of Asian American life from the “model minority” stereotype toward recognition of deeper socioeconomic challenges.

Confronting Discrimination and Structural Inequality

Asian American activists concentrated on dismantling systemic discrimination in employment, housing, education, and policing. Their work targeted longstanding patterns of exclusion that continued despite the repeal of earlier restrictive immigration laws.

Key Areas of Activism

Housing and Urban Renewal: Activists opposed redevelopment programs that threatened Chinatowns, Little Tokyos, and other ethnic enclaves. They emphasized the need for affordable housing, senior services, and protection from displacement.

Labor Rights: Asian American workers—especially in agriculture, restaurants, and garment industries—organized for fair wages and better working conditions. The movement supported farmworker struggles and highlighted exploitation of immigrant labor.

Education Inequality: Community leaders pressed schools and universities to address discrimination, admit more Asian American students from working-class backgrounds, and fund culturally relevant programs.

Building Community Institutions and Local Power

Local empowerment became a defining feature of Asian American movements. Activists founded organizations to provide essential services and promote political participation in neighborhoods historically neglected by government agencies.

Community-Based Institutions

Health clinics addressing language barriers and unequal access to medical care

Legal aid centers that provided representation for immigrants facing discrimination

Cultural and educational programs designed to preserve heritage and foster pride

Neighborhood associations that advocated for housing protections and economic development

These institutions strengthened community infrastructure and created leadership pathways for Asian Americans who had been excluded from municipal decision-making.

Community control: A strategy in which local residents direct institutions and policy decisions affecting their neighborhoods to ensure representation and equitable outcomes.

Community control initiatives helped Asian American neighborhoods resist external political pressures and assert autonomy within rapidly changing urban environments.

Student Activism and Ethnic Studies Campaigns

College campuses in California and across the nation became major organizing centers.

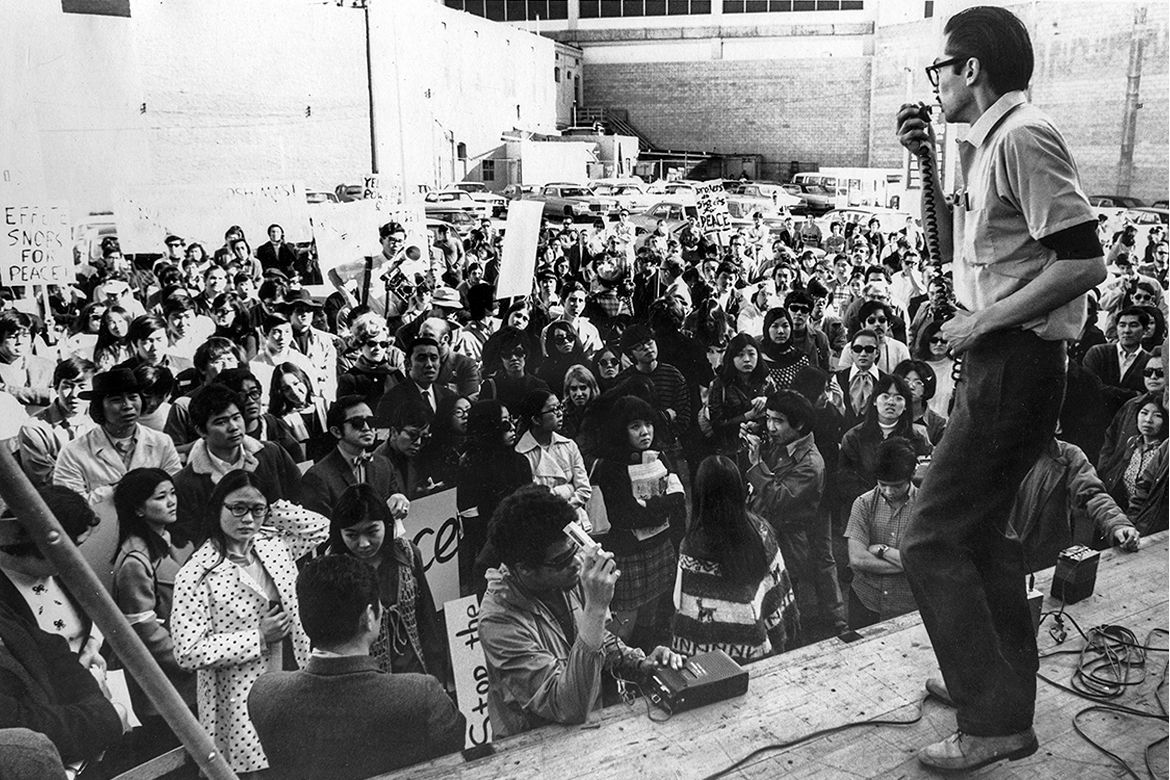

Historian and activist Yuji Ichioka addresses an Asian Americans for Peace rally in Los Angeles in 1970, demonstrating the rise of pan–Asian student activism. The rally linked antiwar politics with demands for racial justice. Though specific to UCLA, it accurately represents the broader student activism discussed in this subtopic. Source.

Asian American students joined coalitions with Black, Latino, and Native American activists to demand Ethnic Studies programs that reflected the histories and experiences of marginalized groups.

The Third World Liberation Front (TWLF)

The TWLF strikes of 1968–69 at San Francisco State College and UC Berkeley were landmark victories.

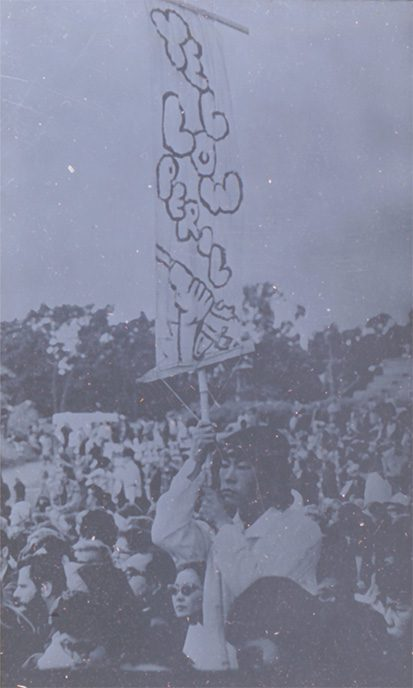

Students rally during the Third World Liberation Strike in San Francisco in 1969, calling for Ethnic Studies and greater campus representation. The “Yellow Peril Supports Black Power” sign illustrates pan–Asian solidarity with other civil rights movements. The image reinforces the collective protest strategies central to this movement. Source.

Students pushed for curriculum transformation, increased faculty diversity, and institutional recognition of Asian American scholarship. These campaigns expanded opportunities for academic research and legitimized the study of Asian American history, politics, and culture.

Immigration, Demographic Change, and Political Mobilization

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 reshaped Asian American communities by ending national-origins quotas and enabling large-scale immigration from across Asia. As new arrivals faced challenges of settlement, activists responded by expanding community organizations, bilingual services, and advocacy networks.

Growing populations also enabled stronger political representation. Activists registered voters, cultivated leadership candidates, and challenged discriminatory local policies. In cities with significant Asian American populations, such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and New York, these efforts contributed to increased visibility in school boards, city councils, and state legislatures.

Confronting Violence and Anti-Asian Racism

Asian American activists confronted rising hate crimes that targeted refugees, immigrants, and long-established communities. The murder of Vincent Chin in 1982—though slightly beyond the AP period—reflected concerns already present in the 1970s about racial scapegoating and economic tensions. Earlier campaigns against police brutality, harassment of Southeast Asian refugees, and discriminatory law enforcement practices demonstrated deep anxieties over racialized violence.

Activists responded by coordinating multiracial coalitions, pressing for civil rights protections, and demanding accountability from public officials. Their work challenged the perception that Asian Americans were passive or apolitical and underscored the broader struggle for safety and dignity.

Expanding Social and Economic Equality

Drawing on the AP syllabus emphasis on claiming greater social and economic equality, Asian American movements advanced reforms that reshaped U.S. social policy debates.

Central Equality Demands

Fair employment protections and affirmative action

Language-access rights in education, healthcare, voting, and courts

Expanded social services for refugees and low-income families

Protection of small businesses in ethnic enclaves

Inclusion in federal anti-discrimination statutes

These efforts connected the Asian American movement to national conversations about civil rights, urban poverty, and multicultural democracy, reinforcing its role in the broader wave of rights-based activism during the 1960s and 1970s.

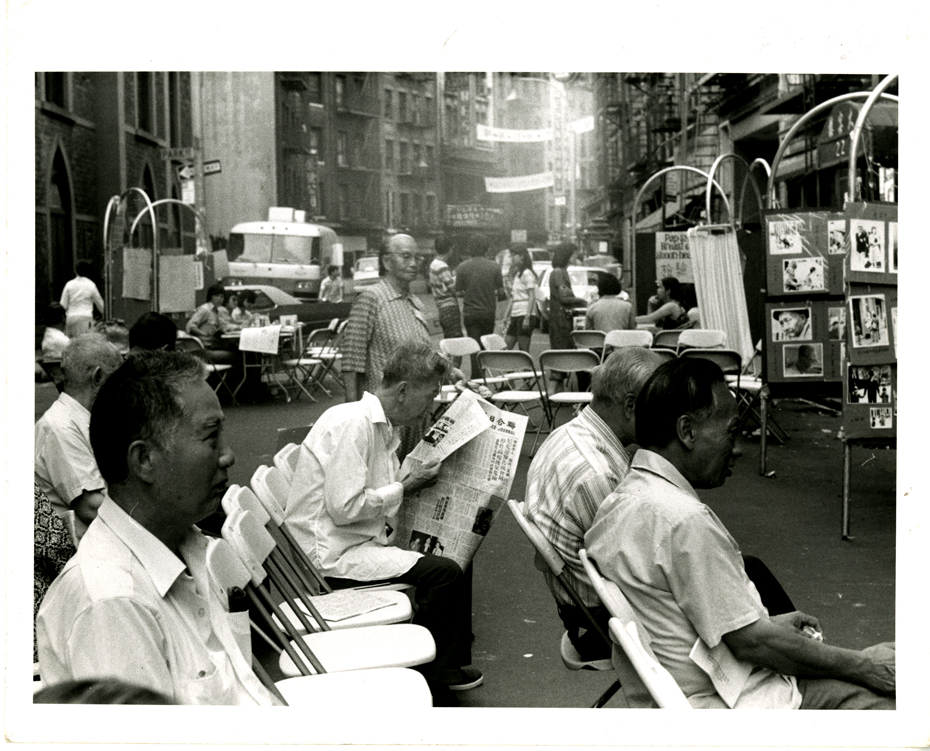

Community members attend the first Chinatown Health Fair on Mott Street in 1971, where activists offered free health screenings and services. The event led to the creation of long-term, community-controlled health institutions. The image includes additional context about the fair’s setting, but directly reinforces the theme of building community power. Source.

FAQ

Asian American activists recognised that individual ethnic groups often lacked sufficient political influence when acting alone. Pan-ethnic unity allowed them to coordinate resources, craft shared narratives about racism, and gain visibility in national debates.

This identity also emerged from shared experiences with immigration restrictions, labour exploitation, and cultural stereotyping.

Student networks and cross-community urban struggles further reinforced the value of collective mobilisation.

Community institutions were intentionally grassroots and culturally specific. They prioritised local decision-making, multilingual services, and culturally competent care.

By contrast, government programmes often failed to address linguistic barriers, bureaucratic discrimination, or the unique needs of refugee and immigrant populations.

These activist-built institutions served not only as service hubs but also as organising centres for political involvement.

Activists borrowed organisational strategies and rhetoric from Black, Chicano, and American Indian movements, including community control, self-determination, and direct action.

They also engaged in multiracial coalitions, recognising shared structural inequalities such as housing segregation and policing practices.

Some borrowed visual and cultural symbolism—such as protest signage linking Asian and Black struggles—to emphasise solidarity and situate their movement within a broader rights-based landscape.

The Vietnam War highlighted issues of racialised foreign policy and anti-Asian sentiment within the United States, motivating activists to challenge wartime stereotypes and domestic discrimination.

Protests also connected Asian American identity to global struggles against imperialism, helping students articulate a political critique that transcended domestic civil rights concerns.

Groups like Asian Americans for Peace used anti-war organising to build alliances and develop pan-Asian consciousness across campuses.

Redevelopment projects often targeted neighbourhoods deemed “blighted,” which disproportionately included Chinatowns and other long-established enclaves. These areas typically housed low-income residents and small immigrant-owned businesses.

Threats included mass displacement, loss of cultural institutions, and erasure of historic districts.

Activists responded through tenant organising, legal challenges, and public demonstrations to preserve affordable housing and protect vulnerable populations.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Identify and briefly explain one way in which Asian American activists sought to build community power during the 1960s and 1970s.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a valid method used by Asian American activists to build community power (e.g., founding health clinics, creating legal aid centres, forming neighbourhood associations, or developing Ethnic Studies programmes).

1–2 additional marks for a clear explanation of how this action strengthened community control or addressed local needs (e.g., improving access to services, resisting displacement, increasing political representation, or promoting cultural pride).

(4–6 marks)

Explain how Asian American movements of the 1960s and 1970s challenged both discrimination and social marginalisation. In your answer, refer to at least two different forms of activism.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award up to 6 marks:

1–2 marks for describing discrimination or social marginalisation faced by Asian American communities (e.g., exclusion from political institutions, poor housing conditions, labour exploitation, lack of culturally relevant education).

1–2 marks for explaining one form of activism that challenged these conditions (e.g., community service institutions, student strikes, labour organising, or anti-racism campaigns).

1–2 marks for integrating a second, distinct form of activism and explaining how it contributed to broader social, political, or economic empowerment.

Stronger answers may show clear connections between activism and outcomes, such as heightened visibility, expanded rights, or institutional reform.