AP Syllabus focus:

‘Many feminists in the 1960s counterculture rejected their parents’ values and argued for major changes in sexual norms and personal freedom.’

Changing Sexual Norms and the Counterculture

The transformation of sexual norms in the 1960s emerged from a broader context of countercultural dissent, expanding feminist activism, and critiques of Cold War-era conformity. These developments reshaped how many Americans thought about gender, sexuality, autonomy, and the role of cultural authority. Feminists within the counterculture often rejected what they viewed as restrictive expectations inherited from their parents, emphasizing the need for greater personal liberation and equality.

Postwar Conformity and the Roots of Change

The postwar era reinforced traditional understandings of sexuality, linking heteronormative family structures, marriage, and rigid gender roles to national stability. Yet several forces destabilized these norms and helped spark new attitudes among younger Americans:

Rising college enrollment expanded youth communities that questioned mainstream authority.

Mass media and cultural experimentation spread new ideas about personal expression.

Continuing civil rights and social justice campaigns encouraged challenges to established hierarchies.

Together, these shifting cultural forces created conditions in which many young Americans found traditional sexual expectations outdated or oppressive.

The Counterculture and Challenges to Traditional Morality

The counterculture, a broad and loosely defined movement of young people rejecting mainstream values, placed personal freedom at the center of its critique. Many participants believed that Cold War-era discipline, materialism, and conventional morality constrained authentic self-expression.

Key features of countercultural critiques of sexual norms included:

A rejection of parental and societal expectations regarding dating, marriage, and gendered behavior.

Advocacy for sexual freedom, emphasizing individual autonomy and emotional openness.

Promotion of alternative living arrangements, such as communal households, that downplayed traditional family structures.

These attitudes reflected frustration with what many saw as the conformity and conservatism of 1950s culture, while also linking personal liberation to broader social transformation.

Feminism, Gender Expectations, and Personal Freedom

Within the counterculture, second-wave feminists advanced demands for gender equality and personal autonomy. These activists challenged assumptions that women should prioritize domestic roles and accept male authority in both public and private spheres.

Second-Wave Feminism: A movement beginning in the early 1960s that sought legal, economic, and social equality for women, focusing on issues such as workplace discrimination, reproductive rights, and cultural norms.

Feminists critiqued double standards in dating, sexuality, and expectations for emotional labor. While countercultural communities often spoke of liberation, many women found that sexist behavior persisted, leading them to articulate more explicit demands for change.

Women march in Washington, D.C., during the Women’s Strike for Equality in August 1970, carrying banners associated with the women’s liberation movement. The demonstration illustrates how second-wave feminists transformed critiques of domestic expectations and double standards into public protest. Some signs reference equal pay and workplace opportunities, extending beyond sexual norms but closely tied to the era’s broader demands for women’s autonomy. Source.

Sexual Liberation and Expanding Social Debate

The sexual revolution, closely associated with the counterculture, further shifted public discussions about morality. New attitudes toward premarital sex, long-term partnerships, and personal experimentation gained visibility among young Americans and appeared in music, literature, and campus activism.

Several developments fueled this transformation:

Greater public availability of birth control, which enabled more women to separate sexuality from marriage and motherhood.

Increasingly visible conversations about sexual identity and personal autonomy.

A belief that fulfilling personal freedom was essential to resisting what activists saw as restrictive Cold War social structures.

These shifts were not universally accepted. Many older Americans viewed changing norms as evidence of declining morals, contributing to an emerging cultural divide.

Tensions Between Idealism and Inequality

Despite their emphasis on liberation, countercultural spaces did not always uphold gender equality. Many women described feeling marginalized within male-dominated groups that prioritized personal freedom for men more than structural equality for women. This contradiction accelerated the growth of independent feminist organizing.

Important tensions included:

Claims that male leaders framed sexual freedom in ways that pressured women rather than empowering them.

Conflicts over leadership roles within mixed-gender activist organizations.

Feminist arguments that true liberation required confronting entrenched sexism within the movement itself.

The pushback from women helped broaden the definition of personal freedom to include not only sexual expression but also autonomy from discriminatory expectations.

Cultural Expression and the Politics of Identity

Music, visual art, and literature reflected shifting sexual norms and amplified critiques of mainstream culture. Popular musicians and writers highlighted themes of authenticity, emotional exploration, and challenges to traditional romance. Countercultural festivals and gatherings celebrated experimentation, reinforcing the idea that personal liberation was both a cultural and political act.

Rejecting their parents’ expectations of early marriage, rigid gender roles, and sexual restraint, many young people experimented with new lifestyles, relationships, and identities.

Students rally against the Vietnam War at Virginia Commonwealth University in 1968. Antiwar activism was a core expression of 1960s youth counterculture, which also questioned consumerism, traditional family expectations, and sexual restraint. The photograph emphasizes political protest, but it helps situate changing sexual norms within a broader culture of student rebellion and experimentation. Source.

These expressions contributed to:

Widespread questioning of traditional authority.

Increased visibility of alternative identities and sexual expressions.

A national conversation about the meaning of morality, freedom, and individual rights in a rapidly changing society.

Activists framed sexuality and identity as political issues, insisting that personal relationships and self-expression were part of broader struggles for freedom.

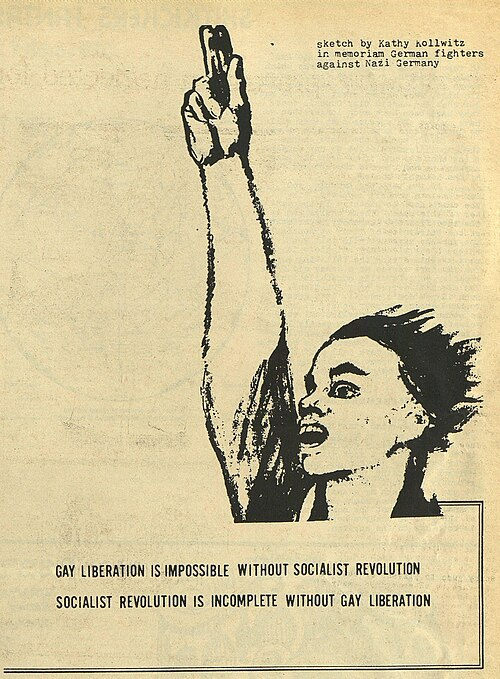

This sketch, used in a New American Movement document on gay liberation, adapts a 1924 drawing by Käthe Kollwitz. It symbolizes collective struggle and the insistence that sexual identity and intimate relationships belonged within debates over power and justice. The source connects gay liberation to left-wing political organizing, which goes somewhat beyond the AP focus but effectively illustrates the era’s language of liberation and rights. Source.

#######################################

Reactions and Social Backlash

Changing sexual norms provoked anxiety among many Americans who associated social stability with traditional morality. Critics argued that the counterculture fostered irresponsibility, undermined the family, and threatened national cohesion. This backlash intensified political and cultural polarization, helping to set the stage for emerging conservative movements that opposed perceived moral decline.

The evolving debates over sexual norms, generational change, and personal freedom in the 1960s reveal how deeply cultural expectations shifted during this period. Feminists and countercultural activists reshaped national conversations about autonomy and identity, challenging long-held assumptions and contributing to new understandings of individual rights.

FAQ

New psychological research questioning strict behavioural norms encouraged people to see sexuality as part of personal identity rather than purely moral conduct.

Studies on emotional fulfilment, self-actualisation, and interpersonal relationships promoted the idea that traditional sexual expectations might restrict individual well-being.

Therapists and counsellors increasingly incorporated these perspectives, helping to normalise more open discussions about sexuality outside marriage.

Musicians helped mainstream new ideas by presenting themes of desire, freedom, and emotional honesty that conflicted with earlier expectations of restraint.

Performers often used provocative lyrics, fashion, and stage behaviour to signal defiance of conventional norms, influencing young audiences.

Certain genres, such as rock and folk, became associated with expressive and experimental attitudes that complemented countercultural critiques of morality.

Communes offered intentional alternatives to nuclear family structures, allowing residents to experiment with shared responsibilities and non-traditional partnerships.

Key features included:

Reduced emphasis on marriage as a social necessity

Collective decision-making about household roles

Greater tolerance for unconventional romantic or sexual arrangements

These environments created space for people to question whether established norms were natural or simply inherited.

As young people asserted greater control over their intimate lives, debates emerged over how much authority parents, schools, or the state should hold over personal decisions.

Concerns about surveillance, censorship, and family oversight highlighted generational tensions.

Many activists argued that privacy was essential for authentic self-expression, linking it to broader calls for personal freedom.

Reactions varied widely. Some religious leaders condemned the perceived erosion of moral standards and emphasised traditional teachings about sexuality.

Others sought to modernise their approaches by:

Addressing generational concerns more openly

Discussing relationships, intimacy, and gender within broader ethical frameworks

Engaging with youth culture to remain socially relevant

These debates contributed to deeper divisions within religious communities about authority, morality, and cultural change.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the counterculture of the 1960s contributed to changing sexual norms in the United States.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award marks for:

1 mark: Identifies a relevant way the counterculture contributed to changing sexual norms (e.g., rejecting traditional morality, promoting sexual freedom).

2 marks: Provides a basic explanation showing how countercultural attitudes or practices encouraged new views on sexuality.

3 marks: Gives a developed explanation with clear linkage between countercultural values and broader societal shifts in sexual norms.

(4–6 marks)

Assess the extent to which second-wave feminism influenced challenges to traditional sexual norms during the 1960s. In your answer, consider both the feminist movement and the wider countercultural context.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award marks for:

4 marks: Describes how second-wave feminism challenged traditional sexual norms, with at least some reference to personal autonomy, gender expectations, or critiques of double standards.

5 marks: Integrates the role of the wider counterculture, showing how feminist activism interacted with or diverged from broader youth movements in shaping sexual norms.

6 marks: Offers a sustained assessment, weighing the relative influence of feminism compared to the counterculture, and demonstrating clear historical reasoning about the extent of feminist impact.