AQA Specification focus:

‘How both demand-side and supply-side shocks affect the macroeconomy.’

Introduction

Unexpected events can disrupt an economy’s equilibrium, creating rapid changes in output, employment, and prices. These are known as demand-side and supply-side shocks.

Understanding Economic Shocks

An economic shock refers to a sudden, unpredictable event that causes a significant change in economic activity, often outside the control of households, firms, or governments.

Economic Shock: A sudden, unexpected event that significantly influences aggregate demand or aggregate supply in an economy.

Economic shocks are categorised as either demand-side (affecting aggregate demand) or supply-side (affecting aggregate supply).

Demand-Side Shocks

Demand-side shocks occur when there are unexpected changes in the components of aggregate demand (AD): consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports.

Examples of Demand-Side Shocks

A sharp fall in consumer confidence, reducing consumption.

Sudden increases in government spending during a crisis.

Global recessions reducing demand for exports.

Rapid monetary tightening reducing investment and borrowing.

Demand-Side Shock: An unexpected event that shifts aggregate demand significantly, either raising or reducing overall demand in the economy.

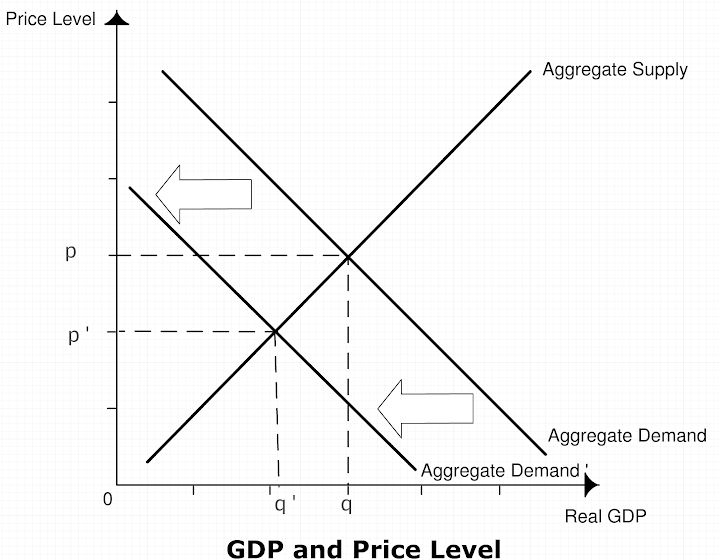

Such shocks cause shifts in the AD curve rather than movements along it. For instance, a global financial crisis reduces demand across multiple sectors, shifting AD leftward.

This diagram depicts the shift of the aggregate demand curve. A rightward shift (AD to AD1) represents an increase in aggregate demand, leading to higher output and price levels. Conversely, a leftward shift (AD to AD2) indicates a decrease in aggregate demand, resulting in lower output and price levels. Source

Supply-Side Shocks

Supply-side shocks involve sudden changes in the costs of production or the availability of resources, affecting aggregate supply.

Examples of Supply-Side Shocks

Sharp rises in oil or gas prices, raising production costs.

Natural disasters disrupting supply chains.

Technological innovations improving productivity.

Sudden changes in taxation or regulations affecting businesses.

Supply-Side Shock: An unexpected event that shifts aggregate supply, either positively (raising potential output) or negatively (reducing productive capacity).

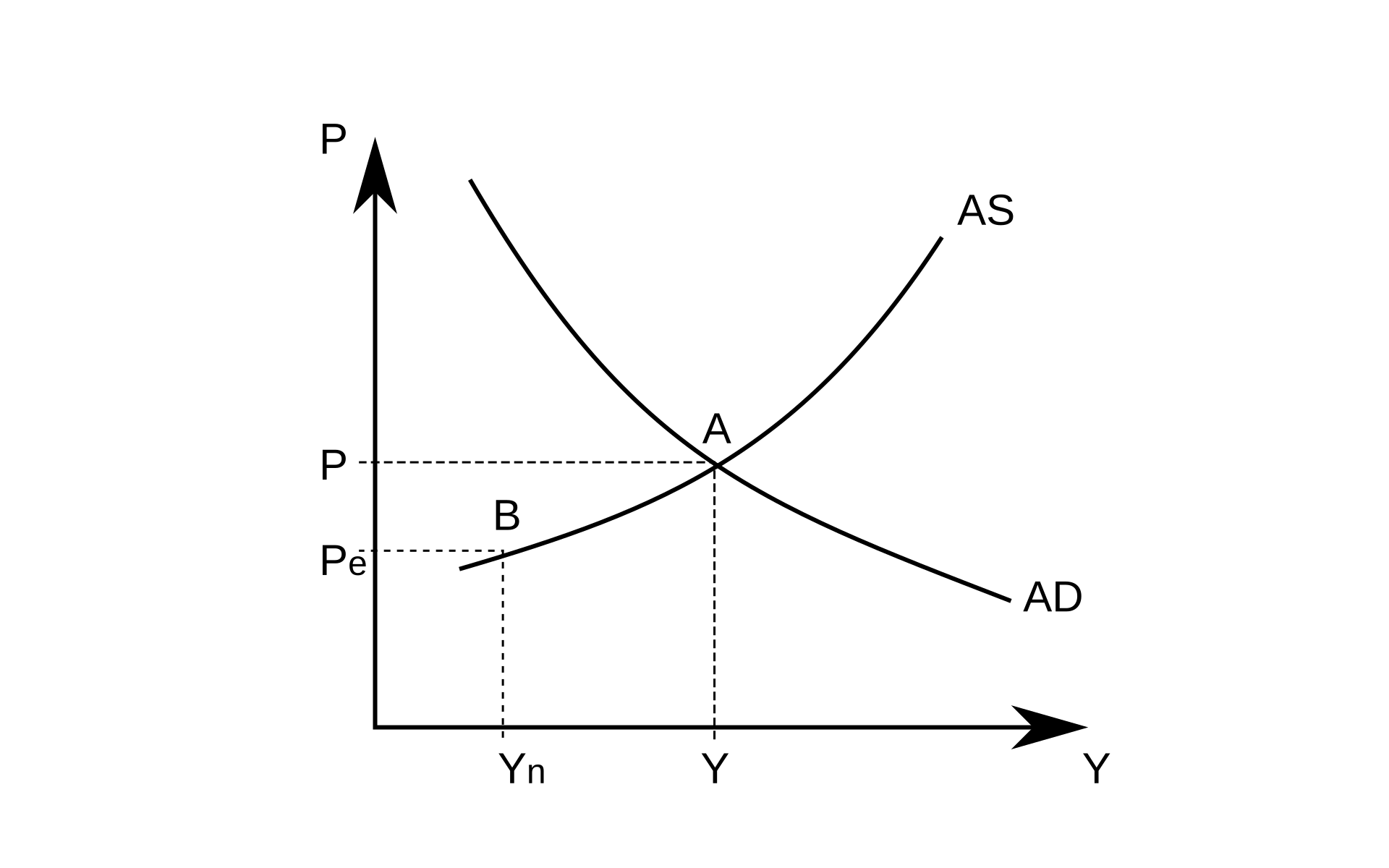

A negative supply shock, such as a spike in energy prices, shifts the short-run aggregate supply (SRAS) curve leftward, increasing prices and reducing output.

This diagram illustrates the shift of the aggregate supply curve. A leftward shift (AS to AS1) signifies a decrease in aggregate supply, resulting in higher prices and reduced output. A rightward shift (AS to AS2) indicates an increase in aggregate supply, leading to lower prices and higher output. Source

Comparing Demand-Side and Supply-Side Shocks

Key Differences

Demand-side shocks change spending behaviour across the economy.

Supply-side shocks alter the cost of production or capacity to produce goods and services.

Demand-side shocks affect the AD curve, while supply-side shocks affect AS curves (short-run or long-run).

Possible Outcomes

A positive demand-side shock (e.g., large rise in investment) can cause higher growth and employment, though with inflationary risks.

A negative demand-side shock (e.g., reduced exports) may cause recessionary pressure and rising unemployment.

A positive supply-side shock (e.g., new technology) can lead to growth without inflationary pressure.

A negative supply-side shock (e.g., oil crisis) leads to stagflation — rising prices with falling output.

Stagflation: A situation where inflation and unemployment rise simultaneously, usually caused by negative supply-side shocks.

Transmission Mechanisms of Shocks

Demand-Side Transmission

Change in aggregate spending → Shifts AD curve → Alters equilibrium output and price level.

Example: a credit crunch reduces borrowing, lowering investment and AD.

Supply-Side Transmission

Change in costs or resources → Shifts SRAS or LRAS → Alters price level and potential output.

Example: an oil supply cut raises production costs, shifting SRAS leftward.

Real-World Illustrations

Demand-Side Shock: Global Financial Crisis (2008)

Collapse of financial markets reduced investment and consumer spending.

AD shifted sharply leftward, leading to deep recession.

Governments responded with fiscal stimulus and monetary easing.

Supply-Side Shock: Oil Price Shocks (1970s)

OPEC oil embargo sharply increased energy prices.

SRAS shifted leftward, leading to stagflation.

Central banks faced policy dilemmas as inflation and unemployment rose together.

Mixed Shock: COVID-19 Pandemic (2020)

Demand collapsed due to lockdowns and uncertainty.

Supply chains were disrupted simultaneously.

Demonstrates how both demand-side and supply-side shocks can occur at once.

Policy Responses to Shocks

Demand-Side Shock Responses

Expansionary fiscal policy: Increased government spending or tax cuts to boost AD.

Monetary policy: Lowering interest rates or quantitative easing to encourage borrowing and investment.

Supply-Side Shock Responses

Short-run measures: Subsidies, energy price caps, or stock releases to reduce costs.

Long-run measures: Investment in innovation, skills, and infrastructure to raise productivity and LRAS.

Graphical Representation in AD/AS Analysis

Demand-side shocks: Shown as shifts in the AD curve.

Supply-side shocks: Shown as shifts in SRAS or LRAS curves.

AD/AS diagrams illustrate new equilibrium output and price levels following shocks.

FAQ

Temporary shocks affect the economy in the short run, such as a one-off energy price spike, and may fade as conditions normalise.

Permanent shocks alter the structure of the economy, such as long-term technological innovations, which shift productive capacity and affect growth trajectories.

Global shocks transmit through trade, investment flows, and financial markets.

A fall in global demand reduces exports.

Rising global interest rates affect domestic borrowing costs.

Supply chain disruptions increase domestic production costs.

Negative supply-side shocks raise production costs and reduce output simultaneously.

This combination causes inflation (from higher costs) and unemployment (from reduced production), producing stagflation — a rare but challenging policy situation.

Shocks often trigger uncertainty in markets, which can magnify their effects.

Consumers may cut back spending.

Firms may delay investment.

Financial markets may react with volatility, worsening the downturn.

Policy choice depends on the type of shock:

For demand-side shocks, fiscal or monetary stimulus is more effective.

For supply-side shocks, structural reforms, subsidies, or regulation changes may be needed.

Policymakers often blend approaches when shocks overlap.

Practice Questions

Define a supply-side shock and give one example. (2 marks)

1 mark for a clear definition: An unexpected event that shifts aggregate supply, either positively or negatively.

1 mark for a valid example: e.g., a sudden rise in oil prices, natural disaster, new technology.

Explain how a negative demand-side shock and a negative supply-side shock might affect output and the price level in an economy. (6 marks)

Up to 2 marks for explaining the effect of a negative demand-side shock:

Leftward shift of AD curve (1 mark).

Leads to lower output and lower price level (1 mark).

Up to 2 marks for explaining the effect of a negative supply-side shock:

Leftward shift of SRAS curve (1 mark).

Leads to lower output and higher price level (stagflation) (1 mark).

Up to 2 marks for analysis and clarity:

Explicit comparison of how each shock differs in its impact on price level (1 mark).

Clear use of economic terminology (e.g., equilibrium, stagflation) (1 mark).