AQA Specification focus:

‘Why there is an inverse relationship between market interest rates and bond prices.’

Understanding the inverse link between interest rates and bond prices is essential for analysing financial markets, investment decisions, and the transmission of monetary policy across the economy.

Bonds and Their Key Features

A bond is a fixed-income security issued by governments or firms to raise finance. When an investor purchases a bond, they are essentially lending money to the issuer in exchange for periodic payments and repayment of the principal at maturity.

Coupon: The fixed annual interest payment paid to the bondholder, usually expressed as a percentage of the bond’s face value.

Maturity: The date on which the bond issuer repays the principal (face value) of the bond to the holder.

The fixed nature of these payments makes bonds highly sensitive to changes in market interest rates, which alter their attractiveness to investors.

Interest Rates in Financial Markets

Interest rates are the cost of borrowing and the reward for saving. Central banks, such as the Bank of England, use policy rates to influence borrowing costs and overall economic activity. Market interest rates often follow central bank decisions but also reflect broader demand and supply conditions in credit markets.

When the central bank raises interest rates, newly issued bonds or other assets become more attractive to investors compared to existing bonds that pay lower coupons. This creates the foundation for the inverse relationship.

Why Bond Prices Move Inversely to Interest Rates

Bondholders value securities based on the return they generate compared to alternatives available in the market. Since coupon payments are fixed, the only way for existing bonds to remain competitive when interest rates change is through price adjustments.

When interest rates rise:

New bonds are issued with higher coupons.

Existing bonds paying lower coupons become less attractive.

Investors demand a lower purchase price to compensate for the lower income.

Result: Bond prices fall.

When interest rates fall:

New bonds offer lower coupons.

Existing bonds paying higher coupons become more attractive.

Investors are willing to pay more to secure these returns.

Result: Bond prices rise.

This mechanism ensures that the yield on existing bonds aligns with prevailing market interest rates.

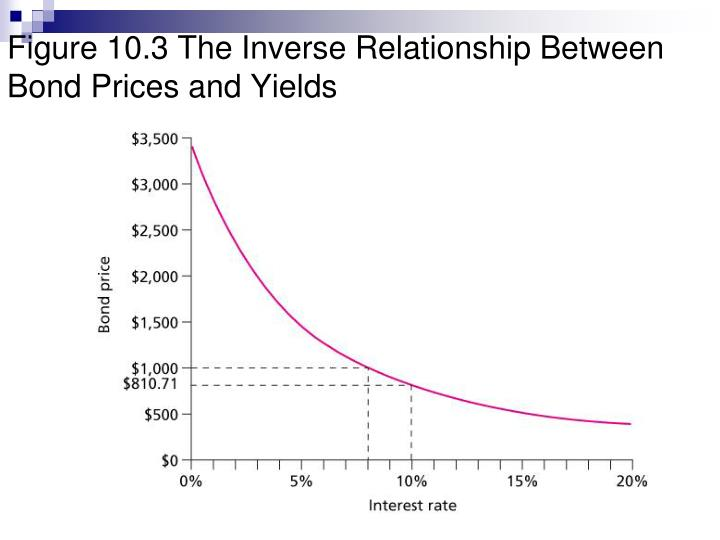

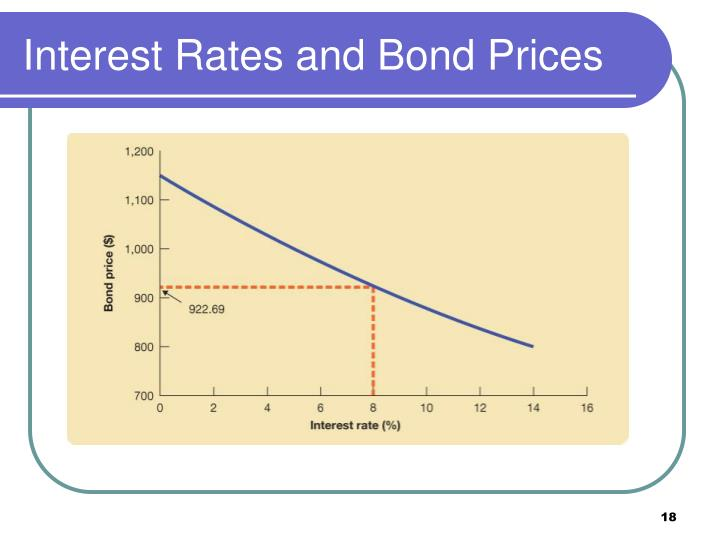

This graph depicts the inverse relationship between bond prices and yields. As interest rates increase, bond prices fall, while falling rates cause bond prices to rise. Source

Yield and Its Connection to Price

Yield: The effective rate of return on a bond, calculated by dividing the annual coupon payment by the current market price of the bond.

If a bond pays a fixed coupon of £50 per year and the market price falls, the yield rises because the same payment represents a larger percentage return on the reduced price. Conversely, if the bond price rises, the yield falls.

This curve shows the inverse relationship between bond prices and interest rates. As interest rates increase, bond prices decrease, and lower rates raise bond prices. Source

Bond Yield (Y) = (Coupon Payment ÷ Current Market Price) × 100

Coupon Payment = Fixed annual interest in £

Current Market Price = The price at which the bond is currently trading

This adjustment mechanism explains why yields and prices move in opposite directions.

The Role of Expectations

The inverse relationship also reflects expectations about future interest rate changes.

If markets expect higher interest rates, investors anticipate falling bond prices, so they may sell bonds in advance, pushing prices down.

If markets expect lower interest rates, investors buy more bonds to lock in higher fixed coupons, raising prices.

Expectations therefore amplify the responsiveness of bond prices to interest rate decisions.

Implications for Investors

The relationship has major consequences for investors and portfolio management:

Risk of capital loss: Bondholders face losses if they must sell bonds after an interest rate rise.

Safe-haven appeal: During falling interest rates, bonds may deliver strong capital gains, making them attractive.

Duration risk: Longer-maturity bonds are more sensitive to interest rate changes because their fixed coupons extend further into the future.

Wider Macroeconomic Implications

The bond market plays a crucial role in the transmission of monetary policy. When the central bank changes its policy rate:

The value of government bonds shifts, affecting yields across the financial system.

Changes in yields influence borrowing costs for firms and households, shaping investment and consumption.

Exchange rates may also move as international investors respond to changing returns on UK bonds.

Through these channels, the inverse relationship between bond prices and interest rates ensures that monetary policy has a direct impact on wider economic activity.

FAQ

Market interest rates are also influenced by investor confidence, inflation expectations, and global financial conditions.

For example:

Rising inflation expectations reduce the real value of fixed coupon payments, pushing bond prices lower.

Safe-haven demand during economic uncertainty may increase bond prices even if interest rates are stable.

International capital flows can shift demand for domestic bonds, affecting their price independently of policy rates.

Long-term bonds lock investors into fixed coupon payments for a longer period.

This means:

When interest rates rise, the opportunity cost of holding older bonds is higher for long maturities.

The price of long-term bonds must fall more sharply to align yields with new market rates.

Short-term bonds, being closer to repayment, are less affected by rate changes.

Bond markets react not only to current rates but also to expected movements.

If investors expect rates to rise, they may sell bonds early, pushing down prices now.

Conversely, if a rate cut is expected, investors may buy bonds in advance, raising current prices.

These anticipatory movements create volatility around central bank announcements.

Inflation reduces the purchasing power of fixed coupon payments.

Higher expected inflation usually leads to higher market interest rates, reducing bond prices.

Lower inflation expectations have the opposite effect, as bonds provide relatively stable real returns.

Inflation-linked bonds exist to reduce this risk, as their coupons adjust with inflation.

Governments issue bonds to finance public spending.

If bond prices fall significantly, new issues must offer higher yields to attract buyers, raising borrowing costs.

This can increase the national debt burden over time.

Governments therefore monitor bond markets closely as part of fiscal sustainability planning.

Practice Questions

Explain why there is an inverse relationship between market interest rates and bond prices. (2 marks)

1 mark for recognising that when interest rates rise, existing bonds with lower fixed coupons become less attractive, so their prices fall.

1 mark for recognising that when interest rates fall, existing bonds with higher fixed coupons become more attractive, so their prices rise.

Discuss how a rise in interest rates affects both bond prices and yields, and explain the implications for investors. (6 marks)

1 mark for correctly stating that bond prices fall when interest rates rise.

1 mark for correctly stating that bond yields increase when bond prices fall.

1 mark for linking the inverse relationship between bond prices and yields.

1 mark for recognising risk of capital loss for investors if they sell bonds after a rate rise.

1 mark for noting that higher yields may attract new investors seeking better returns.

1 mark for clear analysis of implications, e.g., portfolio rebalancing, preference shift towards bonds or alternative assets.

(Maximum 6 marks: reward clear, accurate economic reasoning and application of terminology.)