IB Syllabus focus:

‘Primary removes solids; secondary uses microbes; tertiary removes nutrients/chemicals. Equitable implementation remains challenging across societies.’

Sewage treatment is essential for protecting ecosystems and human health. Understanding its stages and the challenge of equitable access is crucial for sustainable societies.

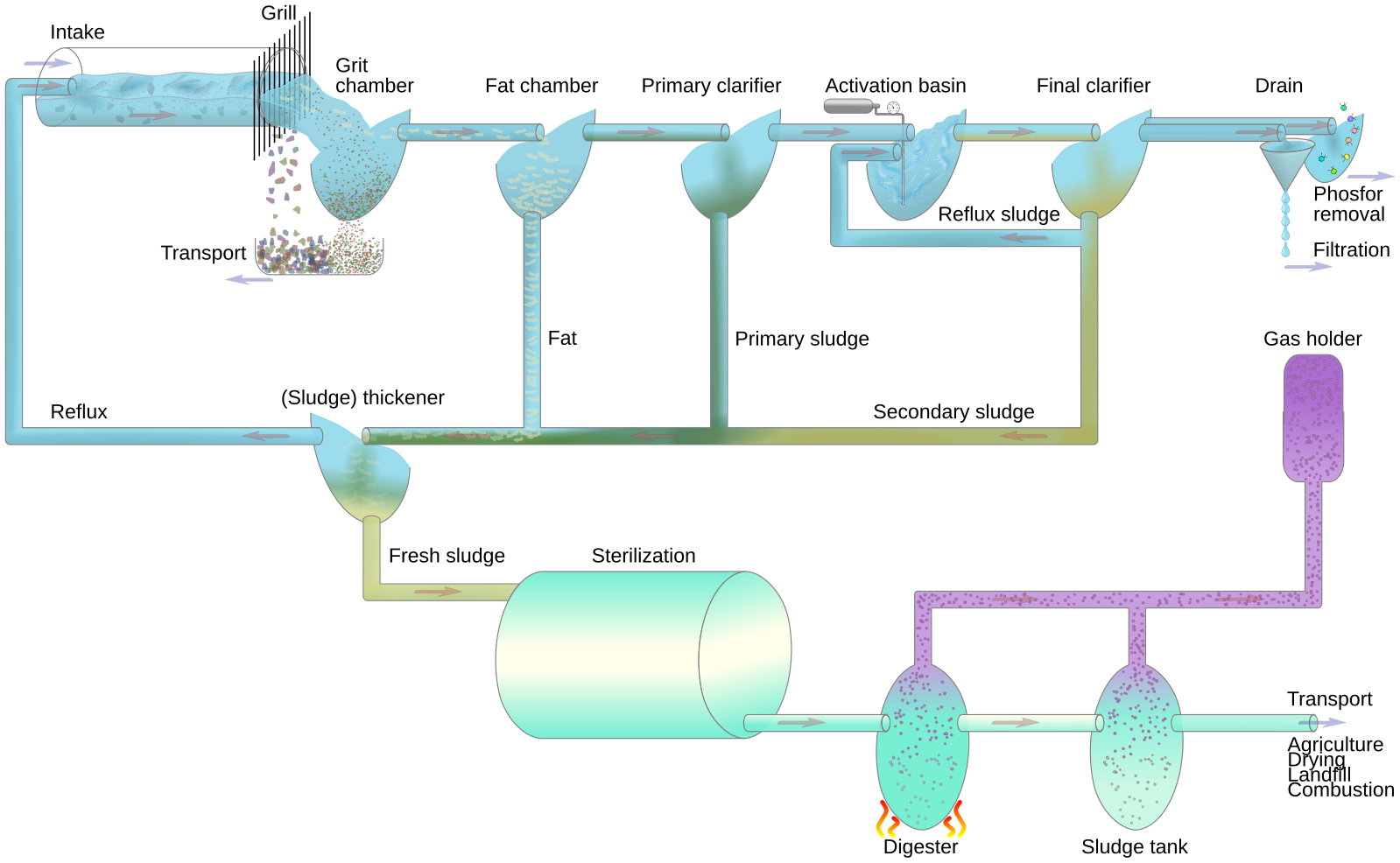

Scheme of a sewage treatment plant showing preliminary/primary removal of solids, secondary biological treatment, and tertiary polishing/disinfection before discharge or reuse. The flow arrows and unit labels help students link processes to outcomes across the three stages. The diagram also depicts sludge treatment units, which extend beyond this subsubtopic’s core focus. Source.

The Stages of Sewage Treatment

Primary Treatment

The primary stage focuses on removing large solids and suspended particles. It is essentially a mechanical process.

Screening removes large debris such as plastics, sticks, or rags.

Sedimentation allows heavier particles to settle as sludge at the bottom of tanks.

Skimming removes lighter materials like fats, oils, and grease from the surface.

This process significantly reduces the solid load but does little to remove dissolved organic material or nutrients.

Secondary Treatment

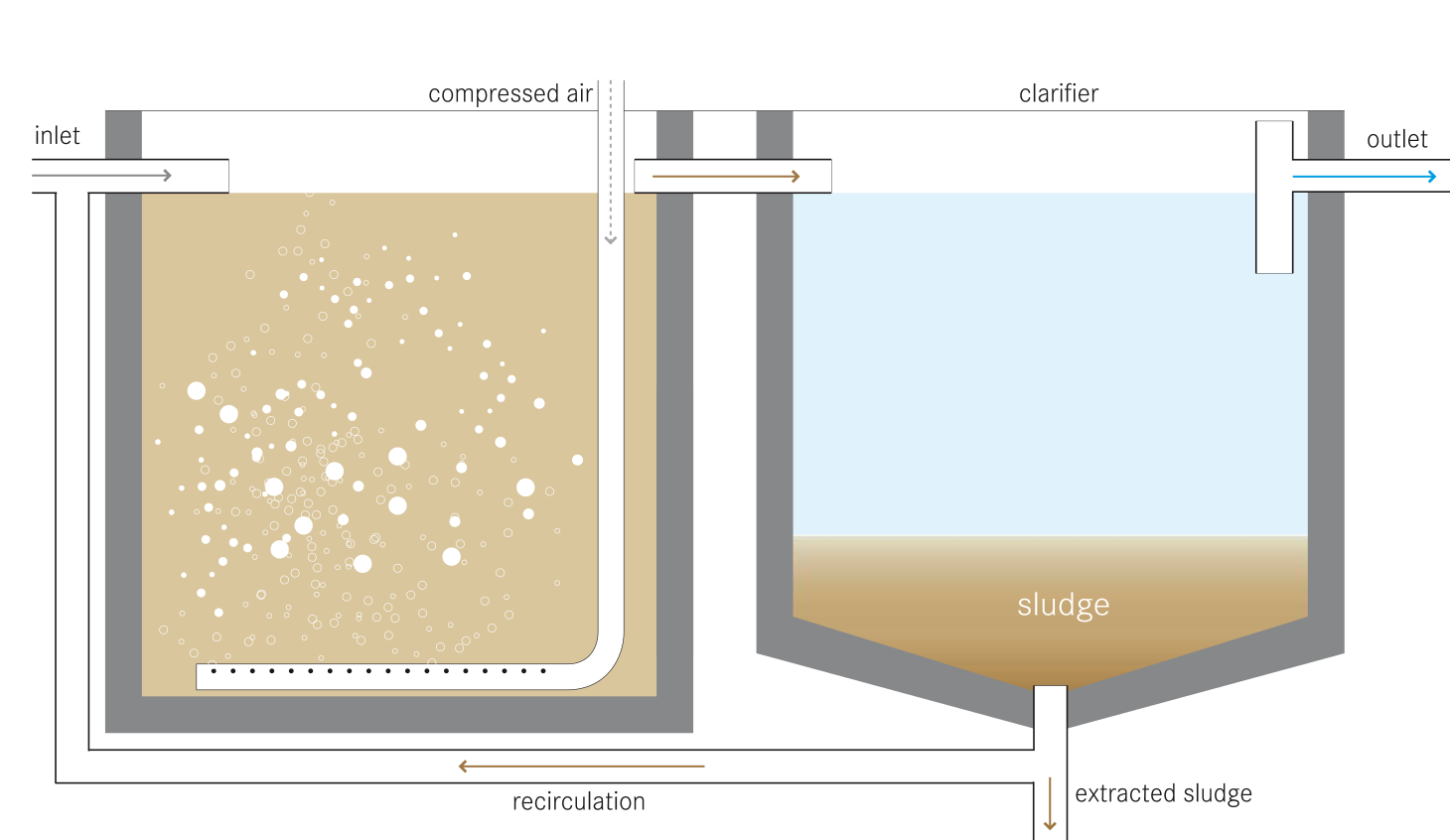

The secondary stage is a biological process that uses microorganisms to break down organic matter.

Activated sludge systems pump air into sewage, encouraging bacteria to decompose organic pollutants.

Trickling filters pass sewage over beds of stones or plastic media, where microbial films digest waste.

Secondary clarifiers separate treated water from microbial biomass, which is either recycled or removed.

Activated Sludge: A treatment process where aerated wastewater supports microbial growth that decomposes dissolved and suspended organic matter.

This stage reduces biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and makes water much safer for discharge.

Diagram of the activated sludge process, including aeration, secondary clarification, and return and waste sludge lines. It illustrates how microbial biomass is recycled to sustain high rates of organic matter removal. Some symbols indicate optional configurations, which are not required beyond recognising the core secondary treatment flow. Source.

Tertiary Treatment

The tertiary stage is an advanced process designed to remove nutrients and chemical contaminants that remain after secondary treatment.

Nutrient removal targets nitrogen and phosphorus, which cause eutrophication if discharged into water bodies.

Filtration systems, such as sand or membrane filters, eliminate fine particulates.

Chemical treatments, including chlorine, ozone, or UV disinfection, kill pathogenic organisms.

Advanced systems may also capture heavy metals and pharmaceuticals.

Tertiary treatment provides the highest water quality, often suitable for reuse in irrigation or even drinking water under strict conditions.

Equity and Sewage Treatment

Unequal Access to Sanitation

Globally, sewage treatment is unevenly implemented, leading to major health and environmental inequalities.

Global map showing national coverage of safely managed sanitation services (2024), highlighting stark differences between regions and income groups. This visual supports the syllabus emphasis on inequitable implementation across societies. The map classes (0–25% to >99%) reflect JMP reporting bands and add detail beyond the minimum syllabus requirement. Source.

Environmental Justice and Human Health

The inequitable implementation of sewage treatment directly affects public health and ecosystem services.

Untreated sewage spreads waterborne diseases such as cholera, dysentery, and typhoid.

Polluted rivers, lakes, and coastal waters suffer oxygen depletion, destroying aquatic life and reducing fisheries.

Inequitable systems often burden marginalised groups, creating environmental justice issues.

Environmental Justice: The fair distribution of environmental benefits and burdens, ensuring that no group suffers disproportionate harm from pollution or resource use.

Challenges of Equity

Ensuring fair access to sewage treatment involves overcoming multiple barriers:

Economic barriers: High costs of building and maintaining tertiary facilities limit adoption in poorer regions.

Technological barriers: Advanced systems require technical expertise, which may not be available locally.

Political and social barriers: Corruption, poor governance, and lack of community engagement slow progress.

Urbanisation pressures: Rapid population growth overwhelms existing treatment systems, particularly in developing megacities.

Sustainable and Equitable Solutions

To improve equity, several approaches are increasingly promoted:

Decentralised treatment systems such as septic tanks or small-scale bioreactors for rural areas.

Low-cost technologies like constructed wetlands that mimic natural purification processes.

Community-led projects ensuring local ownership, maintenance, and equitable distribution of services.

International aid and partnerships to fund infrastructure in regions where domestic resources are insufficient.

Policy reforms requiring governments to uphold sanitation as a human right.

The Role of Sewage Treatment in Sustainable Societies

Sewage treatment directly links to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation. Effective systems reduce disease, improve water security, and protect ecosystems. However, achieving global equity remains one of the greatest environmental and social challenges, requiring a combination of technological innovation, fair policy, and international cooperation.

FAQ

Primary treatment mainly removes large solids and suspended matter through physical processes such as sedimentation and skimming.

Secondary treatment focuses on breaking down dissolved and suspended organic material using microorganisms. It reduces biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), making the water biologically safer but not necessarily nutrient-free.

Tertiary treatment is often required where nutrient pollution poses a significant threat, such as in lakes prone to eutrophication.

In less sensitive ecosystems or in areas with limited financial resources, tertiary treatment may not be implemented because secondary treatment already provides sufficient protection for public health.

Governments influence equity by:

Setting and enforcing national sanitation standards

Funding infrastructure projects in underserved areas

Partnering with NGOs and international agencies

Strong governance ensures that all communities, including marginalised groups, benefit from safe and reliable sewage treatment.

Decentralised systems, such as septic tanks or constructed wetlands, can serve rural or peri-urban communities where centralised plants are not feasible.

They are often cheaper to install and maintain, reduce dependence on large infrastructure, and allow local communities to manage their own sanitation needs.

Key barriers include:

High installation and operational costs

Need for technical expertise and skilled staff

Limited energy resources for advanced processes like UV or ozone treatment

These challenges mean many countries prioritise extending basic secondary treatment before investing in tertiary systems.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Identify two processes carried out in the secondary stage of sewage treatment.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying use of microorganisms/bacteria to break down organic matter.

1 mark for naming a method such as aeration in activated sludge systems or biological digestion in trickling filters.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain how inequitable access to sewage treatment affects both human health and the environment, and suggest one strategy that could reduce this inequity.

Mark scheme:

Up to 2 marks for effects on human health (e.g., spread of waterborne diseases such as cholera, dysentery, typhoid).

Up to 2 marks for effects on the environment (e.g., oxygen depletion, eutrophication, or loss of aquatic biodiversity).

1 mark for a realistic strategy to reduce inequity, such as community-led sanitation projects, low-cost decentralised systems, or international aid.