IB Syllabus focus:

‘WHO and local standards guide safe water and EIAs. Individuals can reduce pollution via consumption choices, peaceful protest, data collection, legal action and lobbying.’

Governance and citizen action are central to addressing water pollution. International organisations, governments, and communities each play roles in ensuring safe water and sustainable management practices worldwide.

International and Local Governance

World Health Organization (WHO)

The World Health Organization (WHO) provides global guidelines on safe drinking water quality, sanitation, and hygiene. These standards shape policies, influence regulations, and ensure a minimum threshold for water safety across countries.

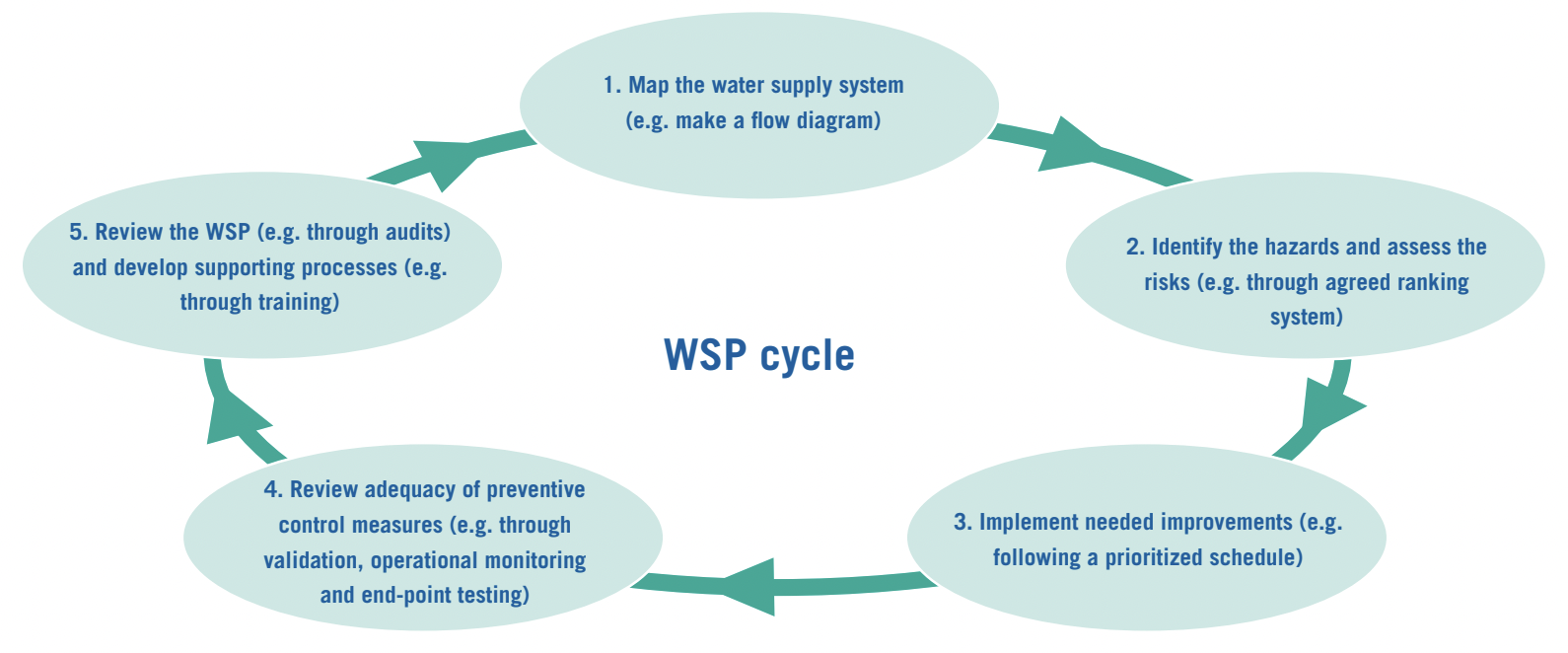

The Water Safety Plan (WSP) cycle shows WHO’s proactive, risk-based governance approach to protect drinking water from catchment to consumer. It highlights mapping the system, identifying hazards, implementing improvements, and ongoing validation and review. Source.

Local Standards

While WHO offers global frameworks, local standards are set by national or regional authorities. These standards consider:

Local hydrological conditions.

Levels of industrial, agricultural, and domestic activity.

Societal priorities for environmental health.

By tailoring regulations, local governance ensures effective water quality management suited to specific contexts.

Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs)

Purpose of EIAs

Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) are legally required in many regions before major projects (e.g., dams, factories, landfills) can proceed.

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA): A systematic process to evaluate potential environmental consequences of proposed projects, including impacts on water resources.

EIAs ensure that development activities do not compromise water quality, aquatic biodiversity, or ecosystem services.

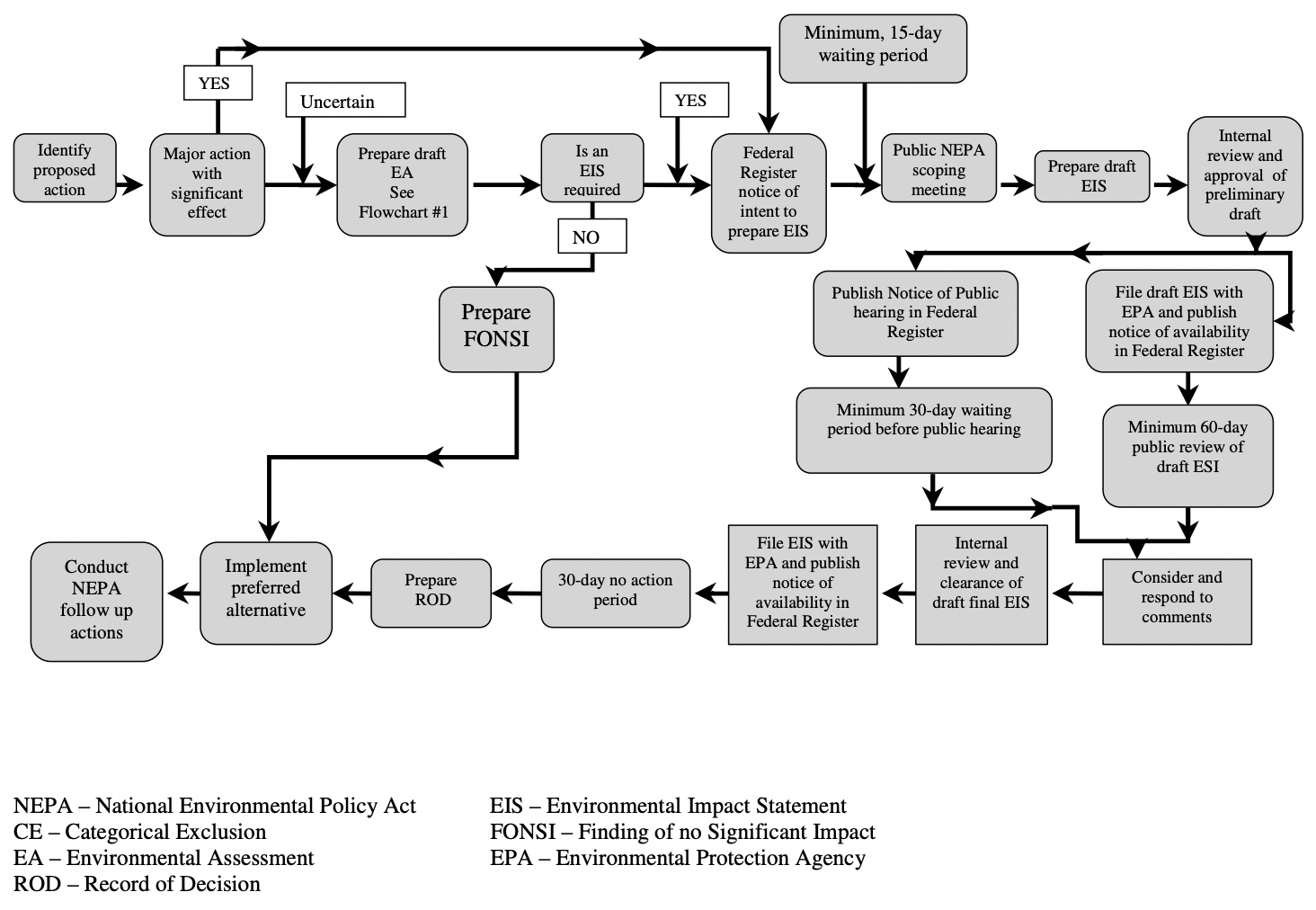

This flowchart outlines the Environmental Impact Statement pathway—scoping, draft statement, public review, and final decision—illustrating how EIAs structure evidence and participation. It is a U.S. NEPA example and includes terms specific to that system (e.g., “Federal Register,” “ROD”), but the staged logic applies broadly. Source.

Steps in EIAs

Screening: Determine if an EIA is required.

Scoping: Identify potential water-related impacts.

Assessment: Analyse predicted impacts on water pollution and quality.

Mitigation: Suggest measures to reduce pollution.

Monitoring: Track compliance and effectiveness of mitigation strategies.

Citizen Action and Participation

Individual Behavioural Choices

Citizens can directly reduce pollution by altering consumption patterns:

Choosing eco-friendly cleaning products.

Reducing use of plastics and single-use packaging.

Proper disposal of chemicals and medicines.

Such lifestyle choices reduce pollutant inputs into waterways.

Peaceful Protest

Peaceful protest enables communities to highlight unsafe practices or demand stricter water regulation. Collective pressure can influence policymakers and corporate actors to act responsibly.

Citizen Science and Data Collection

Role of Data Collection

Communities can engage in citizen science projects to monitor water quality. In these projects, individuals gather and share data on:

Dissolved oxygen and pH levels.

Presence of contaminants such as nitrates or heavy metals.

Changes in aquatic biodiversity.

Volunteers undertake streamside training to collect water-quality and macroinvertebrate data, demonstrating community participation in monitoring. This image exemplifies methods used in citizen science programmes; specific protocols may include DO, pH, nutrients, and habitat assessments. Source.

Citizen Science: The involvement of non-professional scientists in gathering, analysing, and sharing environmental data to support research and policy.

Citizen science projects provide cost-effective, large-scale data sets that inform local authorities and raise public awareness.

Legal Action and Advocacy

Legal Mechanisms

Citizens and communities can use legal frameworks to protect water resources. This may involve:

Filing lawsuits against polluters.

Demanding enforcement of environmental laws.

Requesting remediation and compensation for damages.

Lobbying and Advocacy

Individuals or community groups can also influence policymakers through lobbying, targeting elected officials and institutions to strengthen water protection policies.

The Power of Collective Action

Grassroots Movements

Collective community action has proven effective in stopping environmentally damaging projects, such as polluting factories or poorly regulated mining operations.

Grassroots initiatives often involve:

Public campaigns.

Awareness-raising activities.

Partnerships with NGOs and international bodies.

Equity Considerations

Access to safe water is also an issue of equity. Marginalised communities often lack resources or political voice, making citizen action vital for demanding fair treatment and improved access to clean water.

Interconnected Roles of Governance and Citizens

Governance and citizen action are most effective when combined. International guidelines set minimum standards, local governments implement context-specific policies, and citizens hold institutions accountable while directly contributing to pollution reduction.

Together, these layers of action form a robust system of water governance essential for sustainable societies.

FAQ

The WHO provides science-based frameworks, but enforcement relies on national governments adopting them into law. Training, capacity-building, and technical support programmes help countries align with standards.

Partnerships with NGOs, aid agencies, and local health departments also ensure guidelines are adapted to regional contexts rather than applied in a uniform way.

EIAs are proactive tools designed to predict environmental consequences before a project begins. By highlighting risks early, they prevent long-term problems rather than merely addressing pollution after it occurs.

Mitigation measures identified in an EIA can include wastewater treatment systems, buffer zones to protect rivers, or reduced chemical use in industrial processes.

In these areas, formal monitoring by governments may be limited due to cost or infrastructure challenges. Citizen science fills gaps by producing localised data.

This data can be shared with authorities or NGOs, empowering communities with evidence to demand safer water policies.

Peaceful protests draw public attention and can create immediate pressure on authorities or companies. They are grassroots and highly visible.

Lobbying, on the other hand, involves direct engagement with decision-makers. It is structured, often formal, and works within political systems to influence long-term policy change.

Barriers include lack of education, limited access to monitoring equipment, and political resistance to grassroots demands.

Marginalised groups may also face cultural or legal obstacles to participating in advocacy. Overcoming these requires targeted support, inclusive policies, and partnerships with established organisations.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

State two ways in which citizens can take action to reduce water pollution.

Mark scheme:

Any two of the following, 1 mark each:

Reducing plastic use or choosing eco-friendly products.

Participating in citizen science monitoring.

Peaceful protest to demand stronger water policies.

Engaging in lobbying or advocacy.

Taking legal action against polluters.

Proper disposal of chemicals and medicines.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain how both governance and citizen action contribute to managing water pollution, with reference to equity and public participation.

Mark scheme:

Explanation of governance mechanisms (up to 2 marks):

WHO guidelines or local water standards (1 mark).

Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) for projects (1 mark).

Explanation of citizen action (up to 2 marks):

Citizen science monitoring or data collection (1 mark).

Advocacy, legal action, or peaceful protest (1 mark).

Equity and public participation (up to 1 mark):

Recognition that marginalised groups may lack safe water access; citizen action ensures fair treatment and accountability (1 mark).