IB Syllabus focus:

‘Global treaty reduced production and use of ODSs; a leading example of effective international environmental cooperation.’

The Montreal Protocol is one of the most successful international environmental treaties ever implemented. Signed in 1987, it addressed ozone-depleting substances (ODSs) and showcased effective global cooperation.

Background to the Montreal Protocol

The ozone layer is a region of the stratosphere that absorbs most of the Sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. By the 1970s, scientists observed its depletion, primarily caused by ozone-depleting substances (ODSs) such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) used in refrigeration, aerosols, and solvents.

Ozone-depleting substances (ODSs): Man-made chemicals such as CFCs, halons, and carbon tetrachloride that break down ozone molecules in the stratosphere, accelerating depletion.

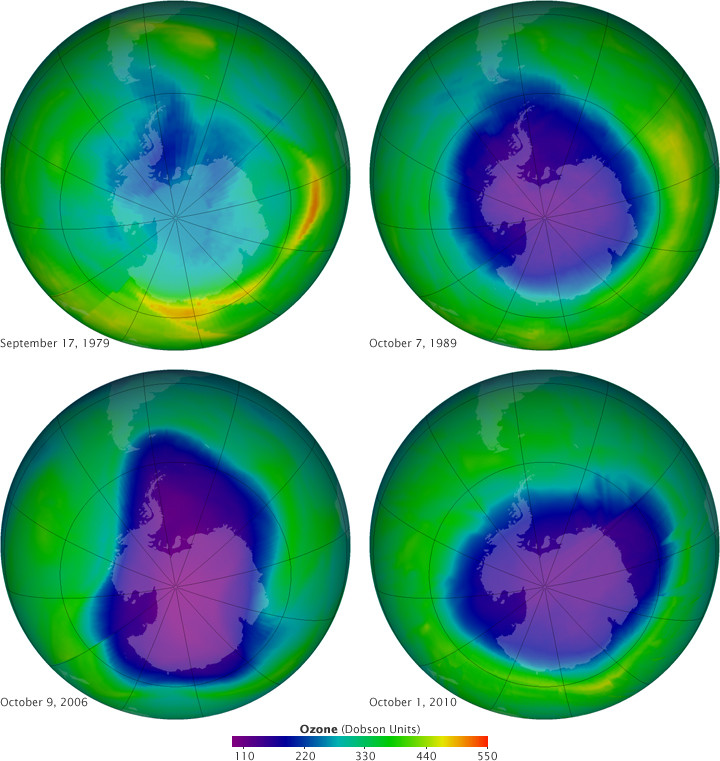

Concerns over ozone holes, especially over Antarctica, prompted international attention. The risk to ecosystems, human health, and climate stability motivated governments to pursue a binding agreement.

Structure and Function of the Protocol

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer was signed under the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer. Its success stemmed from several structural features:

Legally binding commitments: Required nations to phase out ODSs.

Flexibility: Allowed for updates as new scientific evidence emerged.

Differentiated responsibilities: Developed countries phased out ODSs faster, while developing countries received more time and financial support.

Financial mechanism: The Multilateral Fund supported developing nations with technology transfer and compliance costs.

Science-driven updates: Amendments, such as the London (1990) and Kigali (2016) amendments, tightened controls and added substances.

Outcomes and Achievements

The Montreal Protocol is widely recognised as a landmark in environmental governance. Its achievements include:

Phase-out of major ODSs: CFCs, halons, and carbon tetrachloride have been largely eliminated.

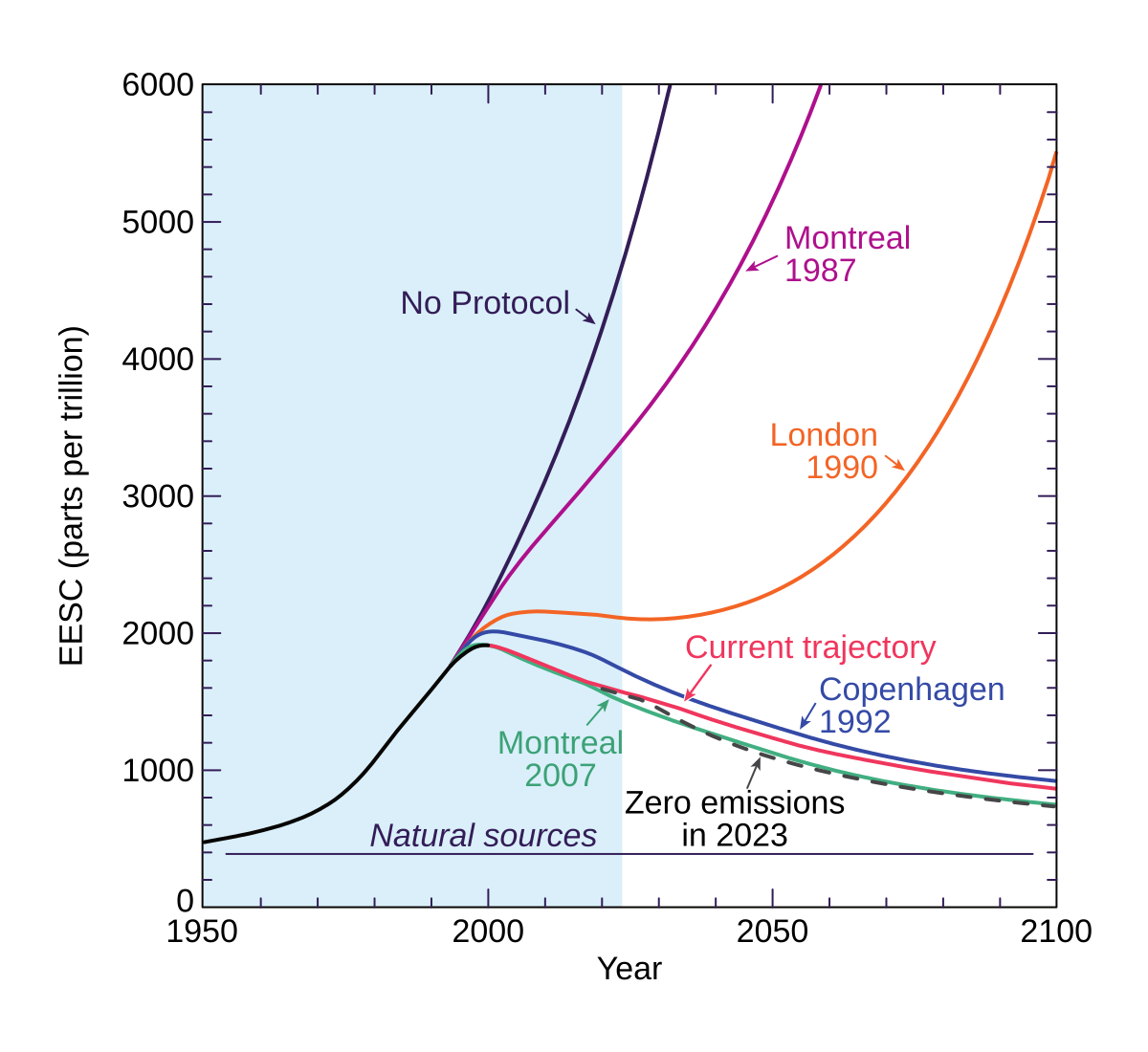

This diagram plots the long-term decline in equivalent effective stratospheric chlorine (EESC) following global phase-outs mandated by the Montreal Protocol, demonstrating reduced ODS loading and progress toward ozone recovery. The curve is a policy-outcome indicator rather than total ozone itself, but it tracks the drivers of depletion. Source.

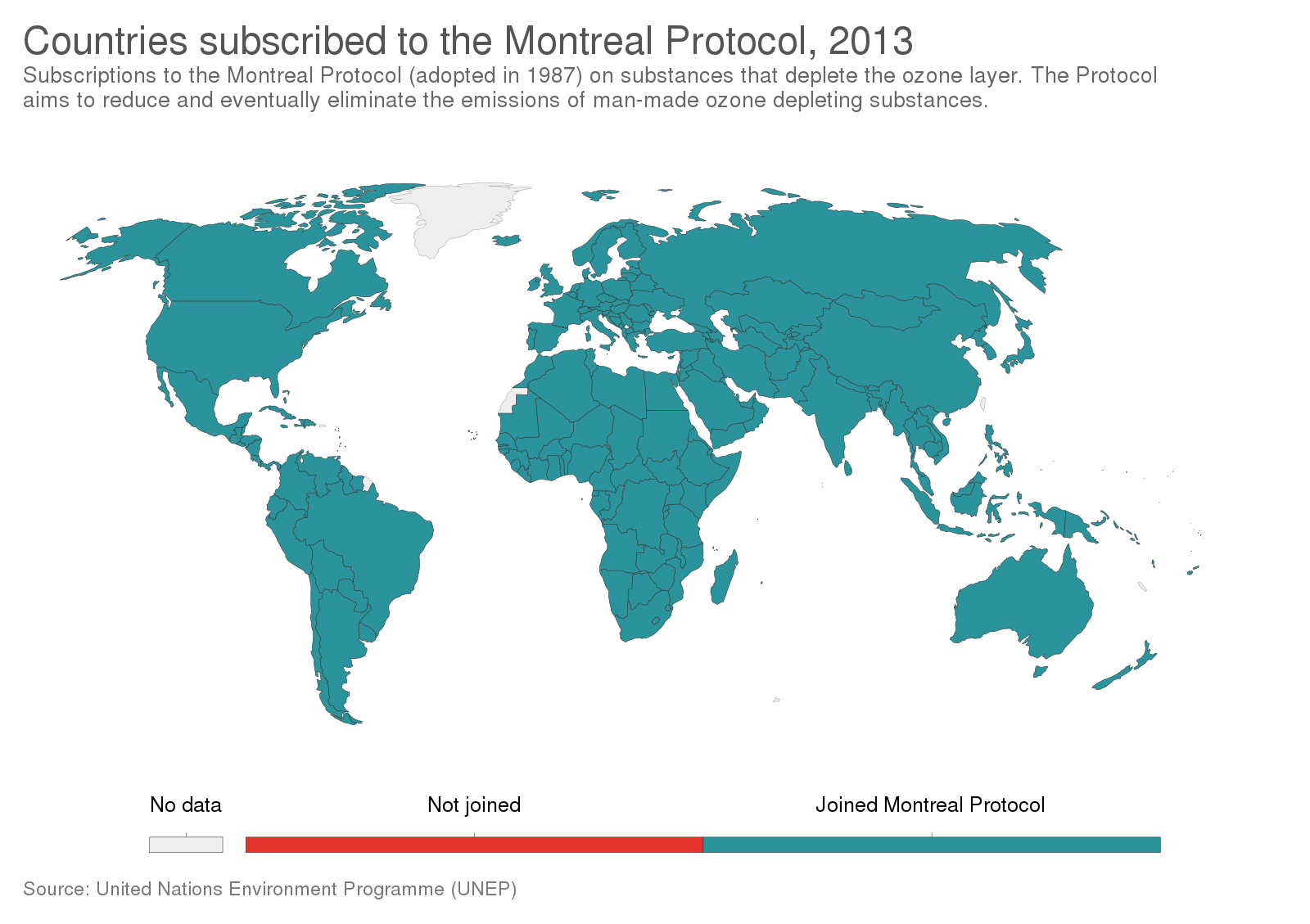

Global participation: Ratified by every member of the United Nations, making it the only treaty with universal ratification.

This world map shows countries subscribed to the Montreal Protocol, illustrating near-universal participation that underpins its effectiveness. The visual emphasises the breadth of cooperation achieved for ozone protection. Source.

Ozone recovery: Scientific evidence shows the ozone layer is on track to recover to pre-1980 levels by mid-21st century.

Panels show the Antarctic ozone hole on days of maximum depletion in 1979, 1989, 2006, and 2010, illustrating severe thinning followed by signs of stabilisation. The figure complements—but does not replace—quantitative indicators by providing a spatial view of ozone distribution. Source.

Climate co-benefits: Many ODSs are also potent greenhouse gases. By eliminating them, the Protocol indirectly prevented significant global warming.

Demonstration of cooperation: Showed how international governance can achieve results when science, policy, and global equity align.

Why the Montreal Protocol is Seen as a Success

Several factors explain why the Montreal Protocol stands out as an effective treaty:

Clear Scientific Consensus

The discovery of the Antarctic ozone hole and strong scientific evidence created urgency and credibility.

Visible and Immediate Risks

UV radiation increases from ozone depletion caused health risks such as skin cancer and cataracts, alongside ecosystem damage. This helped mobilise political will.

Economic Alternatives

Industries developed and adopted substitutes for ODSs relatively quickly, making compliance less costly than initially feared.

Adaptive Framework

The treaty was designed to evolve with scientific updates. New harmful substances could be added, ensuring long-term effectiveness.

Continuing Challenges and Lessons

Although successful, the Montreal Protocol also highlights ongoing challenges:

Illegal trade in ODSs persists in some regions, undermining progress.

Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which replaced CFCs, do not deplete ozone but are powerful greenhouse gases. The Kigali Amendment addresses this, linking ozone protection with climate mitigation.

Some ecosystems, such as polar regions, may take longer to recover due to climatic complexities.

The Protocol remains a case study in climate governance, offering lessons for tackling other global issues such as climate change:

Multilateral cooperation is essential for problems that transcend borders.

Financial and technological support increases participation from developing countries.

Treaties must be adaptable to new science and conditions.

Key Takeaways for IB ESS Students

The Montreal Protocol is a global treaty that successfully reduced ODS production and use.

It is an example of effective international environmental cooperation.

Universal ratification and compliance mechanisms set it apart from many other treaties.

Beyond ozone recovery, it also provided significant climate change mitigation benefits.

It demonstrates how science, policy, and global cooperation can align to solve planetary challenges.

FAQ

The detection of the Antarctic ozone hole in 1985 provided dramatic visual evidence of ozone depletion. This, combined with decades of atmospheric chemistry research, convinced policymakers of the urgent need for international action.

Unlike many previous treaties, the Montreal Protocol was legally binding, enforceable, and flexible. It introduced specific reduction targets, clear timelines, and the ability to strengthen measures through amendments as science advanced.

The Multilateral Fund, established in 1991, financed projects that helped developing countries phase out ozone-depleting substances.

Provided technical assistance

Funded new equipment and training

Ensured developing countries could meet obligations without economic disadvantage

The availability of affordable substitutes for ODSs made compliance easier. Health risks, such as skin cancer, were immediate and tangible, making public and political support stronger than for less visible climate risks.

The Kigali Amendment (2016) targeted hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), substitutes for CFCs. Though not ozone-depleting, HFCs are potent greenhouse gases. This expanded the Protocol’s scope, linking ozone protection with climate mitigation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Identify two reasons why the Montreal Protocol is considered a successful international environmental treaty.

Mark scheme:

Award 1 mark for each valid reason (maximum 2 marks).

Possible answers include:

Universal ratification by all UN member states (1 mark)

Significant phase-out of major ozone-depleting substances (1 mark)

Creation of a financial mechanism to support developing countries (1 mark)

Evidence of ozone layer recovery (1 mark)

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain how the structure of the Montreal Protocol contributed to its effectiveness as a global environmental agreement.

Mark scheme:

Clear explanation of legally binding commitments (1 mark)

Reference to flexibility through amendments/updates as scientific knowledge developed (1 mark)

Explanation of differentiated responsibilities between developed and developing countries (1 mark)

Mention of the Multilateral Fund or technology transfer to assist compliance (1 mark)

Coherent discussion of how these features ensured long-term success and participation (1 mark)

(Any five well-explained points, up to a maximum of 5 marks.)