OCR Specification focus:

‘Interpret and predict reactions involving electron transfer in redox systems.’

Introduction

Electron-transfer reactions underpin many redox processes in chemistry. Understanding how electrons move, and why, enables reliable prediction of reaction pathways, spontaneity, and reagent behaviour across diverse chemical systems.

Understanding Electron Transfer in Redox Systems

Electron-transfer reactions occur when electrons move from a reducing agent to an oxidising agent, changing oxidation numbers and producing new species. Predicting these reactions requires interpreting oxidation states, identifying feasible electron movements, and determining whether one species can reduce or oxidise another under given conditions.

Oxidation Numbers

Assigning oxidation numbers allows chemists to track electron flow. Oxidation involves an increase in oxidation number, while reduction involves a decrease.

Oxidation Number: A numerical value representing the number of electrons an atom has gained, lost, or shared compared to the uncombined element.

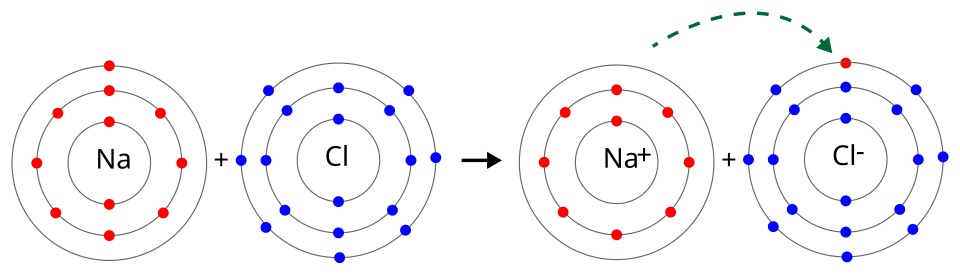

Oxidation numbers track electron loss and gain in a redox change. Sodium’s oxidation number increases as it loses an electron, while chlorine’s decreases as it gains an electron, showing the direction of electron transfer. Source

Accurate oxidation-number assignment ensures clear identification of which species undergo oxidation or reduction within a redox system.

A range of rules governs oxidation-number determination, many of which appear consistently across OCR A-Level Chemistry. These include fixed values for elemental forms, typical oxidation states of oxygen and hydrogen, and algebraic balancing of neutral and charged species.

Identifying Oxidising and Reducing Agents

Electron-transfer prediction depends on distinguishing the two fundamental reactive roles:

Oxidising Agent: A species that gains electrons and is reduced during a redox reaction.

A sentence must appear here before the next definition.

Reducing Agent: A species that loses electrons and is oxidised during a redox reaction.

The relative strengths of oxidising and reducing agents govern whether a proposed electron-transfer process will occur. Strong oxidising agents accept electrons readily, while strong reducing agents readily donate electrons.

Half-Equations and Electron Flow

Redox systems are often interpreted using half-equations, which separately show oxidation and reduction processes. Balancing half-equations requires balancing atoms, charge, and electron number.

In aqueous systems, additional species such as H⁺, OH⁻, or H₂O may appear to achieve correct atom and charge balance under acidic or alkaline conditions.

Interpreting half-equations allows direct prediction of electron movement:

Identify oxidation (electron loss).

Identify reduction (electron gain).

Ensure electron numbers match when combining half-equations.

Determine overall feasibility based on electron-transfer direction.

These steps align with the OCR expectation to “interpret and predict reactions involving electron transfer in redox systems.”

Predicting Feasible Electron-Transfer Reactions

To determine whether an electron-transfer reaction is likely to occur, chemists combine knowledge of oxidation states, half-equations, and characteristic redox behaviour of species.

Key principles for prediction

Species with high oxidation numbers often act as oxidising agents.

Species in low oxidation states frequently act as reducing agents.

Electron transfer occurs from the reducing agent to the oxidising agent.

Combined half-equations must show consistent electron balancing.

Using Redox Series or Potentials to Support Prediction

Although detailed potential calculations belong to later subtopics, qualitative reasoning still helps predict electron transfer. Species with a greater tendency to be reduced (strong oxidising agents) typically accept electrons from species with a strong tendency to be oxidised.

Students should focus on the conceptual relationship between electron affinity, oxidation state, and redox behaviour, in line with the specification requirement to interpret and predict reactions in redox systems without needing formal electrode-potential calculations at this stage.

Constructing Electron-Transfer Pathways

When analysing potential redox reactions:

Stepwise approach

Assign oxidation numbers to all atoms undergoing change.

Identify oxidation and reduction processes.

Propose half-equations showing electron movements.

Check whether electrons lost equal electrons gained.

Combine half-equations to predict the overall reaction.

Check physical or chemical conditions if relevant (e.g., aqueous medium, acidic/alkaline environment).

These steps ensure systematic analysis of electron transfer.

Common Patterns in Electron-Transfer Reactions

Understanding recurring patterns supports faster interpretation:

Typical oxidising agents

Transition-metal ions in high oxidation states (e.g., MnO₄⁻ in acid).

Halogens such as Cl₂ and Br₂.

Oxyanions like Cr₂O₇²⁻ under acidic conditions.

Typical reducing agents

Metallic elements such as Zn or Fe.

I⁻ ions, which readily lose electrons.

Lower oxidation-state metal ions, e.g., Fe²⁺.

Recognising these general behaviours helps predict feasible redox reactions before writing full equations.

Balancing and Combining Half-Equations to Predict Outcomes

Successful prediction demands consistently balanced charge and mass. When combining half-equations:

Multiply each half-equation by appropriate factors to balance electrons.

Combine oxidation and reduction half-equations.

Cancel electrons and any other species appearing on both sides.

Present the final balanced redox equation.

This method is essential for structuring the electron-transfer process clearly and aligns directly with the OCR requirement to interpret reactions involving electron movement.

Assessing Reaction Direction

For any proposed electron transfer:

Determine if the reducing agent can supply electrons to the oxidising agent meaningfully.

Evaluate whether oxidation-state changes are chemically reasonable.

Consider whether the environment (acidic/alkaline/aqueous) supports the required half-equation adjustments.

Check stoichiometric compatibility between species.

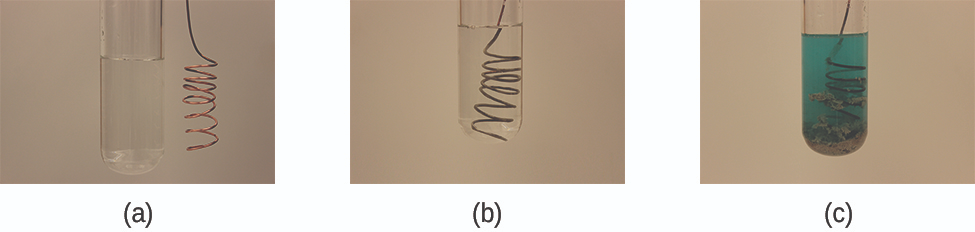

Copper displaces silver from solution as electrons transfer from copper atoms to silver ions. The deposited silver metal and formation of blue Cu²⁺ ions provide visual evidence of a displacement redox reaction; the experimental setup detail slightly exceeds syllabus requirements. Source

Electron-transfer reactions occur only when electrons can move from a species able to donate them to one capable of accepting them, consistent with chemical reactivity patterns.

Applying Interpretation Skills to Unfamiliar Systems

The specification states that students must be able to interpret and predict reactions involving electron transfer even when encountering unfamiliar chemical systems. This requires:

Applying oxidation-number rules to any new species.

Recognising functional similarities between unfamiliar ions and known oxidising or reducing agents.

Constructing plausible half-equations based on general principles.

Ensuring electron balance regardless of the specific species involved.

This skill ensures confident handling of new redox contexts across A-Level Chemistry.

FAQ

Fractional oxidation numbers arise when the average oxidation state is calculated across identical atoms in a molecule or ion, such as in Fe₃O₄.

They do not indicate partial electron transfer during a reaction. Instead, they reflect mixed oxidation states within the substance. When predicting electron transfer, focus on the change in oxidation number before and after the reaction rather than the fractional value itself.

The reaction medium can change which species are able to gain or lose electrons.

For example:

In acidic solutions, H⁺ ions may participate in half-equations.

In alkaline solutions, OH⁻ ions may be required for balancing.

These differences can alter feasible electron-transfer pathways without changing the fundamental redox roles of the reacting species.

Electron transfer may be thermodynamically favourable but kinetically slow.

Factors include:

High activation energy.

Formation of protective oxide layers on metals.

Lack of effective collisions between reactants.

These kinetic barriers can prevent observable reactions even when electron transfer is predicted.

Many redox-active species have characteristic colours linked to their oxidation state, especially transition-metal ions.

A colour change often indicates:

Formation of a new oxidation state.

Transfer of electrons between species.

Observing colour changes helps confirm predicted electron-transfer reactions in aqueous systems.

Half-equations allow complex redox reactions to be broken into simpler oxidation and reduction steps.

This approach:

Clarifies electron movement.

Avoids reliance on memorised reactions.

Helps ensure charge and mass balance.

Using half-equations makes it easier to predict electron transfer in unfamiliar chemical systems.

Practice Questions

A redox reaction occurs when zinc metal is added to aqueous copper(II) sulfate.

a) Identify which species is oxidised.

b) State one piece of evidence, in terms of electron transfer or oxidation numbers, that supports your answer.

(2 marks)

a) Zinc is oxidised.

1 mark

b) One of the following points:

Zinc loses electrons.

The oxidation number of zinc increases (from 0 to +2).

Zinc acts as the reducing agent by donating electrons to copper(II) ions.

1 mark

Iron(II) ions react with acidified dichromate(VI) ions, Cr2O7²⁻, in aqueous solution.

a) Using oxidation numbers, explain which species is oxidised and which is reduced in this reaction.

b) Write the balanced half-equation for the oxidation process.

c) Explain how the direction of electron transfer can be predicted for this redox system.

(5 marks)

a)

Iron(II) ions are oxidised.

1 markDichromate(VI) ions are reduced.

1 mark

b) Correct balanced oxidation half-equation:

Fe²⁺ → Fe³⁺ + e⁻

1 mark

c) Any two of the following explanations:

Iron(II) ions have a lower oxidation state and can lose electrons.

Dichromate(VI) ions contain chromium in a high oxidation state and readily gain electrons.

Electrons are transferred from Fe²⁺ to Cr2O7²⁻ in the reaction.

The reducing agent donates electrons to the oxidising agent.

2 marks