OCR Specification focus:

‘Calculate standard cell potentials; predict feasibility and discuss kinetic and concentration limitations.’

Standard cell potentials help chemists assess whether redox reactions are thermodynamically feasible. Understanding feasibility and the limitations of predictions is crucial when applying electrode potentials to practical systems.

Standard Cell Potentials

Standard cell potentials form the basis of judging whether an electron-transfer reaction should occur under standard conditions. These conditions are defined as 298 K298\ \text{K}298 K, 1 atm1\ \text{atm}1 atm, and solutions at 1 mol dm⁻³ concentration. A standard cell potential arises from two half-cells connected to allow electron flow, enabling comparisons of different redox systems.

When discussing cell potentials, the essential measurement is the standard electrode potential, which reflects the tendency of a half-cell to gain electrons. The standard cell potential is then calculated from the difference between the potentials of the two half-cells.

Standard Cell Potential (E°cell) = E°(positive electrode) − E°(negative electrode)

E°(positive electrode) = Standard reduction potential of the electrode acting as the cathode

E°(negative electrode) = Standard reduction potential of the electrode acting as the anode

A positive value for E°cell indicates a thermodynamically feasible reaction under standard conditions because the overall electron flow from negative to positive electrode is energetically favourable.

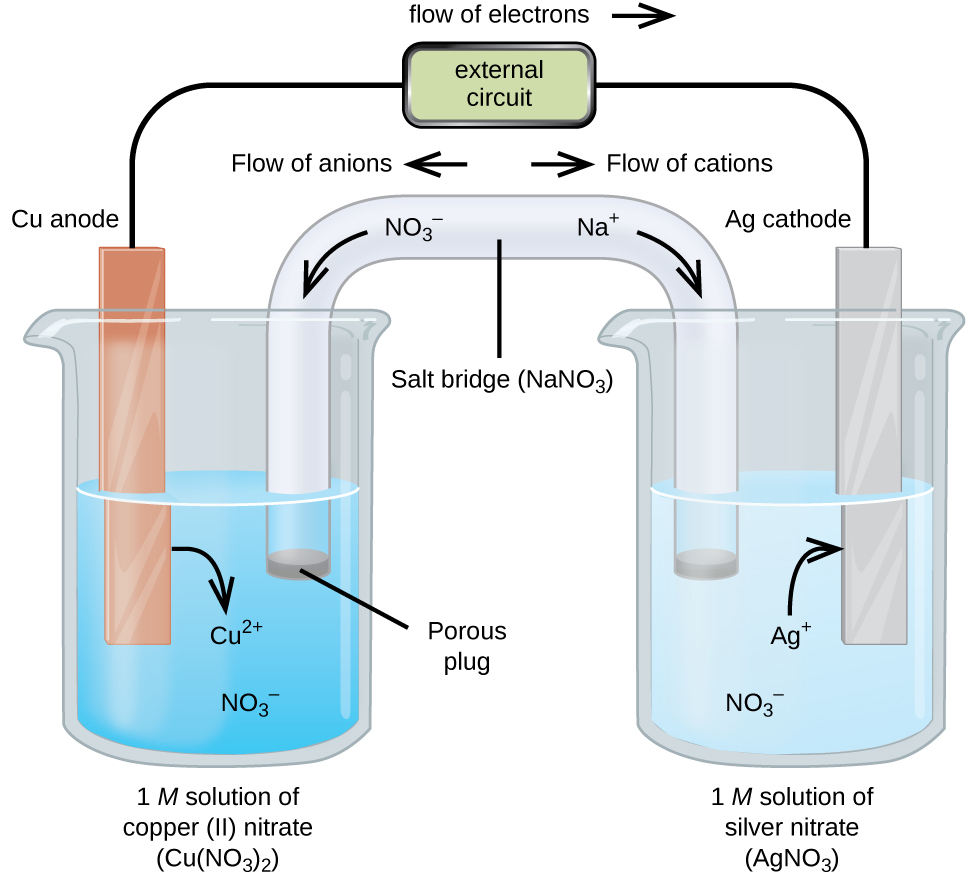

This diagram shows a galvanic cell with a salt bridge maintaining electrical neutrality as the redox reaction proceeds. Electrons move through the external circuit from the anode (oxidation) to the cathode (reduction), while ions migrate through the salt bridge to balance charge. Source

Using Cell Potentials to Predict Feasibility

Thermodynamic Feasibility

Standard electrode potentials allow predictions about whether an oxidation–reduction process should occur spontaneously. Feasibility is assessed by combining half-equations and judging the sign of E°cell.

Feasibility: The likelihood that a reaction can occur spontaneously under specified conditions based on thermodynamic criteria.

To construct a feasible reaction:

Identify the half-equation with the more positive E° value; this acts as the reduction half-cell.

Identify the half-equation with the less positive (or more negative) E° value; this acts as the oxidation half-cell.

Reverse the oxidation half-equation before combining.

Subtract the oxidation potential from the reduction potential to obtain E°cell.

A positive cell potential suggests the reaction is thermodynamically favourable, yet real systems exhibit limitations that must be considered.

Conditions Required for Standard Values

Cell potentials in practice may deviate from standard values when concentration, pressure, or temperature differ. Even small changes may significantly shift predicted feasibility.

Key influences on predicted potentials include:

Concentration of ionic species

Partial pressure of any gases involved

Temperature, which affects the position of equilibrium and particle energy

Activity of ions, sometimes deviating from ideal behaviour at higher concentrations

Because many redox reactions involve equilibrium systems, altered conditions may shift equilibria, modifying the actual electrode potential and affecting predicted spontaneity.

Limitations of Using Standard Cell Potentials

Despite the usefulness of cell potentials in predicting thermodynamic tendencies, students must appreciate their limitations. Standard electrode potentials do not always accurately predict whether a reaction will occur in real conditions.

Kinetic Limitations

Even when E°cell is positive, reactions may not occur due to slow reaction rates.

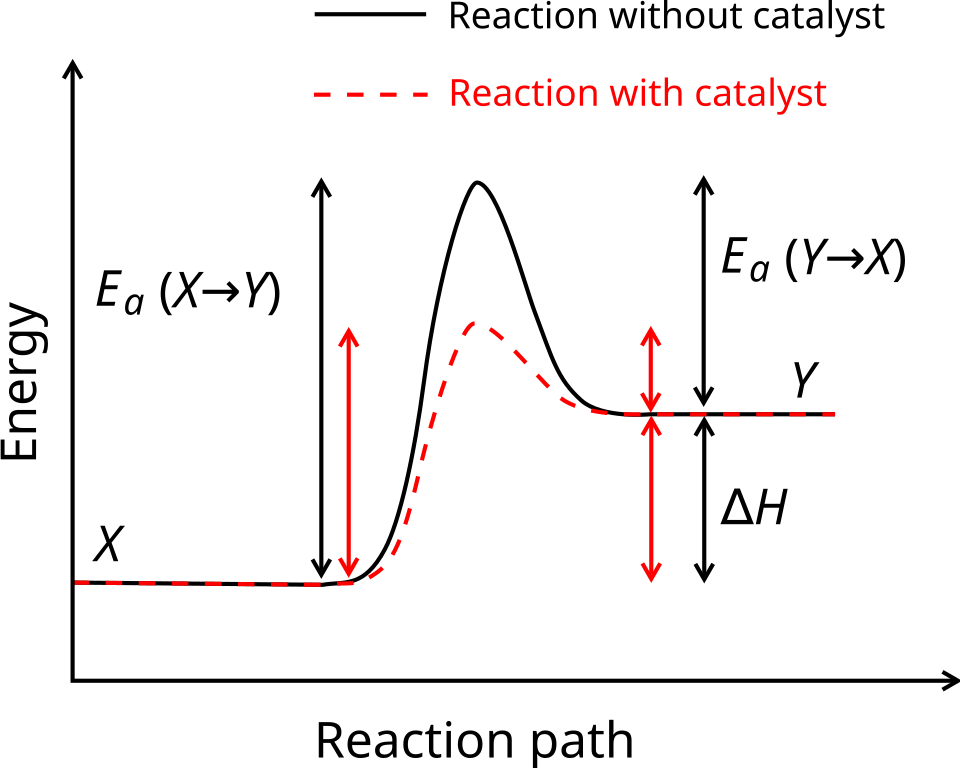

This reaction profile illustrates how a reaction can be thermodynamically favourable while still being kinetically hindered by a large activation energy. Lowering the activation barrier increases reaction rate without changing the overall energy difference between reactants and products. Source

Kinetic Limitation: A restriction on a reaction’s progress caused by slow reaction rate or high activation energy despite favourable thermodynamic conditions.

Between definition blocks, it is important to emphasise that kinetic issues arise because many redox reactions involve significant structural or bonding changes.

Typical kinetic barriers include:

High activation energy, preventing reactants from achieving the necessary transition state

Strong covalent bonds requiring substantial energy to break

Electron-transfer steps that are inherently slow

Surface limitations in heterogeneous redox systems where electron transfer depends on phase boundaries

These kinetic challenges mean that a negative ΔG or positive E°cell alone does not guarantee an observable reaction rate. For example, certain redox systems predicted to be feasible may proceed immeasurably slowly without a catalyst.

Concentration Limitations

Standard cell potentials assume ion concentrations of 1 mol dm⁻³, but real conditions rarely match these values. Variations in concentration directly affect electrode potentials through shifts in equilibrium.

Important concentration-related considerations:

Low concentration of a reacting ion may reduce its ability to accept or lose electrons, lowering its effective reduction/oxidation potential.

High concentration may increase ionic activity but also intensify inter-ionic interactions, potentially reducing ideality.

Dilution effects may move equilibrium positions, altering whether the reduction or oxidation process is favoured.

These changes can render a reaction non-feasible even if the standard cell potential suggests spontaneity.

Influence of Reaction Conditions

Beyond concentration and kinetics, several other factors may limit feasibility:

pH, especially where hydrogen or hydroxide ions participate in half-equations

Solvent effects, altering ionic stability

Electrode surface contamination, which may inhibit electron transfer

Gas solubility, where low solubility restricts reaction rate in gas-involving systems

Students should recognise that predicted cell potentials rely on idealised conditions and must be adjusted when analysing real chemical environments.

Applying Predictions in Practical Electrochemistry

In practical electrochemical systems such as sensors, batteries, and industrial redox processes, understanding feasibility and limitations is essential. Standard cell potentials provide valuable initial predictions, but chemists must also consider practical factors such as ion mobility, electrode design, and operational conditions to determine how effectively a cell will perform.

Bullet-pointed considerations for real applications include:

Thermodynamic feasibility, based on E°cell

Reaction rate, potentially requiring catalysts

Concentration stability, influenced by operating conditions

Reversible and irreversible behaviour, linked to reaction mechanisms

Environmental conditions, including temperature and pH

These elements together determine whether a redox reaction predicted to be favourable will proceed at a usable rate and with observable voltage in real systems.

FAQ

The standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) is defined as 0.00 V by convention to provide a common reference point.

This allows all other standard electrode potentials to be measured and compared consistently.

Because E°cell values are calculated using differences in electrode potentials, the absolute value is less important than relative comparisons between half-cells.

Overpotential is the extra voltage required to drive an electrochemical reaction at a practical rate.

It arises due to kinetic barriers such as slow electron transfer or surface resistance at electrodes.

As a result, the measured cell voltage is often lower than the predicted standard cell potential.

A large positive E°cell indicates strong thermodynamic favourability but does not account for reaction rate.

If the reaction has a very high activation energy or involves complex electron transfer steps, it may proceed extremely slowly.

This makes the reaction difficult to observe without catalysts or specialised conditions.

When gases are involved in redox reactions, changing pressure alters the effective concentration of the gaseous species.

Increasing pressure generally favours reactions consuming gas molecules, which can increase the measured cell potential.

Lower pressure has the opposite effect, potentially reducing feasibility under non-standard conditions.

Industrial systems rarely operate under standard conditions of concentration, temperature, or pressure.

Electrode materials, impurities, and large-scale mass transport effects can significantly alter reaction behaviour.

As a result, standard cell potentials are used as a starting guide rather than a precise predictor of real performance.

Practice Questions

A redox reaction has a positive standard cell potential, E°cell.

Explain why this does not always mean the reaction will occur at a measurable rate under standard conditions.

(2 marks)

Award marks as follows:

1 mark for stating that a positive E°cell only indicates thermodynamic feasibility or that the reaction is energetically favourable.

1 mark for explaining that the reaction may be kinetically limited, for example due to a high activation energy or slow electron transfer, meaning the reaction rate is very slow.

Standard electrode potentials are used to predict the feasibility of redox reactions.

Explain how standard cell potentials are used to predict feasibility and discuss two limitations of these predictions.

(5 marks)

Award marks as follows:

1 mark for stating that standard cell potential is calculated from the difference between the standard electrode potentials of the two half-cells.

1 mark for stating that a positive E°cell indicates that the reaction is thermodynamically feasible or spontaneous under standard conditions.

1 mark for explaining a kinetic limitation, such as high activation energy, slow reaction rate, or surface limitations at electrodes.

1 mark for explaining a concentration limitation, such as non-standard ion concentrations changing electrode potentials or shifting equilibrium.

1 mark for clear linkage between these limitations and why a reaction predicted to be feasible may not proceed or may not produce the expected voltage.