OCR Specification focus:

‘Carry out Fe²⁺/MnO₄⁻ and I₂/S₂O₃²⁻ titrations; follow good volumetric technique.’

Redox titrations rely on carefully controlled electron-transfer reactions to determine the concentration of an oxidising or reducing agent. Students must be confident with apparatus handling, reaction monitoring and endpoint recognition.

Understanding Redox Titration Techniques

Redox titrations involve oxidation–reduction reactions in which electrons are transferred between chemical species. These titrations differ from acid–base titrations because colour changes often arise naturally from the reacting species, removing the need for an external indicator. The two core redox titrations required by the OCR specification are Fe²⁺/MnO₄⁻ titrations and I₂/S₂O₃²⁻ titrations, and each relies on consistent, accurate volumetric technique.

Essential Volumetric Technique

A strong command of volumetric skills ensures titration data are reliable and reproducible. Students must use equipment correctly and follow established laboratory procedure.

Key steps in accurate titration work

Rinse pipettes, burettes and volumetric flasks with the solutions they will contain.

Record initial and final burette readings to the nearest 0.05 cm³.

Ensure there are no air bubbles in the burette tip before starting.

Swirl the conical flask continuously during titration to maintain homogeneous mixing.

Add the titrant dropwise near the endpoint for precision.

Repeat titrations to obtain two or more concordant titres, typically within ±0.10 cm³.

The role of oxidation and reduction

Redox titrations centre on an electron-transfer process. When a species undergoes oxidation, it loses electrons; when it undergoes reduction, it gains electrons. Recognising these processes helps predict colour changes and ensure correct interpretation of the endpoint.

Oxidation: Loss of electrons by a chemical species, often increasing oxidation number.

A properly executed redox titration produces a sharp, well-defined endpoint because the colour arises directly from the oxidising or reducing species themselves.

Fe²⁺/MnO₄⁻ Titrations

These titrations use acidified potassium manganate(VII) as the oxidising agent in the burette and a reducing agent such as Fe²⁺ in the conical flask. The permanganate ion, MnO₄⁻, is intensely purple, making it “self-indicating”.

Why the titration is self-indicating

As MnO₄⁻ is added to the Fe²⁺ solution, it is reduced to almost colourless Mn²⁺. The Fe²⁺ is oxidised to Fe³⁺. The solution remains colourless until all Fe²⁺ has reacted; one extra drop of MnO₄⁻ then gives a permanent pale pink tint signalling the endpoint.

Good practice specific to MnO₄⁻ titrations

The titration must occur in excess dilute sulfuric acid to ensure complete reduction of MnO₄⁻ to Mn²⁺.

Do not use hydrochloric acid, as chloride ions may themselves undergo oxidation.

Avoid carbonate contamination, which can affect Fe²⁺ concentration.

Carry out titrations swiftly to minimise air oxidation of Fe²⁺.

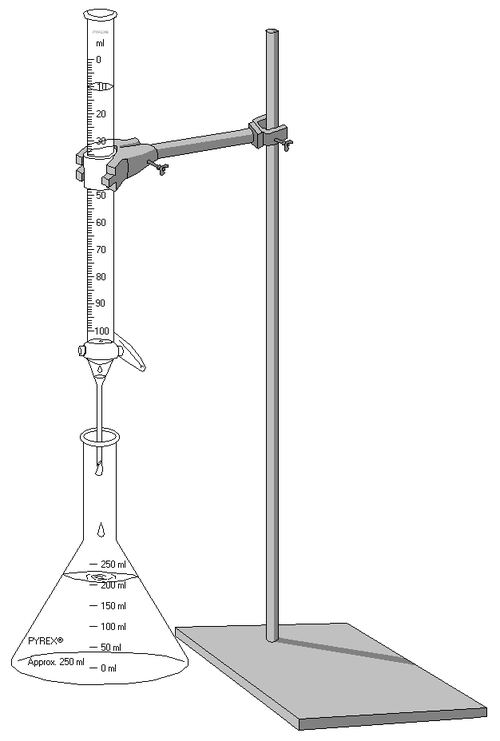

Clamp the burette vertically, place a conical flask beneath the jet, and use a white tile to make subtle endpoint colour changes easier to see.

A labelled titration setup showing a burette delivering titrant into a conical flask. The diagram highlights correct apparatus positioning for controlled addition and accurate endpoint detection. Source

Normal sentence to separate blocks and maintain structural clarity.

Endpoint (redox titration): The point at which a permanent and faint colour persists, indicating slight excess of the oxidising or reducing agent.

The success of MnO₄⁻ titrations depends on consistent swirling, careful acidification and sensitive colour recognition.

I₂/S₂O₃²⁻ Titrations

In these titrations, iodine (I₂) is generated in situ and titrated with sodium thiosulfate, S₂O₃²⁻, a reducing agent. Because iodine has a brown colour, a starch indicator is required for a clear endpoint.

How iodine–thiosulfate titrations work

An oxidising agent converts I⁻ into I₂ in the sample mixture.

The brown I₂ solution is titrated with colourless S₂O₃²⁻.

As S₂O₃²⁻ reduces I₂ to I⁻, the brown colour fades.

When the colour becomes pale straw, starch is added to form a blue-black starch–iodine complex.

Near the endpoint, the blue colour disappears suddenly, showing that all iodine has reacted.

Key procedural requirements

Add starch only when most iodine has reacted, otherwise the complex formed is too stable and slows the reaction.

Store thiosulfate carefully, as it decomposes in light.

Standardise the thiosulfate solution if high accuracy is required.

Maintain consistent flask swirling to avoid localised concentrations of iodine.

Take burette readings at eye level and record the bottom of the meniscus to minimise parallax error.

A close-up of a burette meniscus illustrating the correct point for volume readings. Accurate eye-level alignment reduces parallax error and improves titre reliability. Source

Importance of standardised technique

Because multiple species appear during iodine titrations, consistent practice is essential. Students must recognise subtle colour transitions and add titrant cautiously to avoid overshooting the endpoint. Starch must be freshly prepared when possible to ensure reliable colour formation.

Add starch near the endpoint so the blue–black colour disappears sharply when iodine has been fully reduced by thiosulfate.

Solutions from an iodometric titration before and after the endpoint. The disappearance of colour indicates complete reduction of iodine by thiosulfate. Source

Normal sentence placed here to maintain continuity before any equation block that may appear.

Overall Redox Process (I₂/S₂O₃²⁻) = I₂ + 2S₂O₃²⁻ → 2I⁻ + S₄O₆²⁻

I₂ = Molecular iodine, provides the initial brown colour

S₂O₃²⁻ = Thiosulfate ion, reduces iodine

S₄O₆²⁻ = Tetrathionate ion, product of thiosulfate oxidation

The visible colour change from blue-black to colourless provides a sharp endpoint, making this titration highly suitable for analysing oxidising agents or determining concentration changes in redox reactions.

Ensuring Accuracy and Avoiding Common Errors

Accurate redox titrations depend on avoiding procedural errors and understanding sources of uncertainty.

Common issues and how to prevent them

Endpoint overshooting: add titrant dropwise when close to colour change.

Inconsistent acidification (MnO₄⁻ titrations): always add sufficient dilute sulfuric acid.

Incorrect starch timing (I₂/S₂O₃²⁻ titrations): introduce starch only at pale straw colour.

Contamination of solutions: rinse apparatus thoroughly and use freshly prepared reagents when appropriate.

Poor mixing: swirl continuously to disperse added titrant evenly.

A disciplined, methodical approach ensures that both Fe²⁺/MnO₄⁻ and I₂/S₂O₃²⁻ titrations deliver reliable, reproducible data suitable for quantitative redox analysis.

FAQ

Fe²⁺ ions are slowly oxidised to Fe³⁺ by oxygen in the air. This reduces the true concentration of Fe²⁺ in the solution.

Preparing the solution immediately before use minimises oxidation and improves accuracy. Acidifying the solution also helps stabilise Fe²⁺ during the titration.

Sulfuric acid provides the acidic conditions required without interfering in the redox reaction.

Hydrochloric acid can be oxidised by MnO₄⁻, producing chlorine gas

Nitric acid acts as an oxidising agent itself

Using sulfuric acid avoids side reactions that would affect the titre.

Sodium thiosulfate reacts rapidly and stoichiometrically with iodine, producing a clear colour change at the endpoint.

It is colourless in solution, allowing iodine’s colour changes to be observed clearly. Its reaction products do not interfere with the starch indicator.

Sodium thiosulfate decomposes slowly, especially when exposed to light and heat.

To maintain accuracy:

Store the solution in a dark container

Keep it at room temperature

Standardise the solution regularly if high precision is required

This ensures consistent results in iodine–thiosulfate titrations.

Continuous swirling ensures even mixing of reactants, preventing localised excess of titrant.

Without proper mixing:

The endpoint may appear prematurely

Colour changes may be uneven or misleading

Good mixing leads to a sharp, accurate endpoint and improves the reliability of titre values.

Practice Questions

In an Fe²⁺/MnO₄⁻ redox titration, explain why potassium manganate(VII) does not require an external indicator.

(2 marks)

Award marks as follows:

States that MnO₄⁻ is coloured (purple) and acts as its own indicator. (1 mark)

Explains that a permanent pale pink colour appears when MnO₄⁻ is in excess, indicating the endpoint. (1 mark)

A student carries out an I₂/S₂O₃²⁻ redox titration to determine the concentration of an oxidising agent.

a) Describe how the endpoint is identified in this titration. (3 marks)

b) Explain why starch solution is added close to the endpoint rather than at the start of the titration. (2 marks)

(5 marks)

a) Endpoint identification (3 marks)

Award marks as follows:

States that iodine gives the solution a brown colour which fades during titration. (1 mark)

States that starch forms a blue-black complex with iodine. (1 mark)

Correctly identifies the endpoint as the sudden disappearance of the blue-black colour. (1 mark)

b) Timing of starch addition (2 marks)

Award marks as follows:

States that adding starch too early forms a very stable iodine–starch complex. (1 mark)

Explains that this slows the reaction or makes the endpoint less sharp or harder to observe. (1 mark)

Total: 5 marks